A blog of the Wilson Center

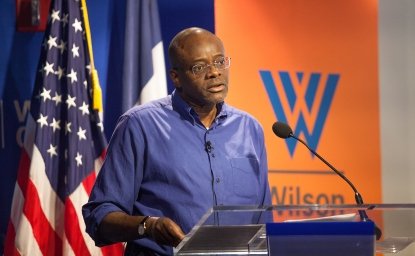

Raul Pangalangan, a former judge with the International Criminal Court (ICC) at The Hague and a distinguished scholar in international and constitutional law, has devoted his career to the intersections of human rights, governance, and legal theory. As a Wilson Center fellow, he continues to explore the complexities of justice on the global stage, combining practical experience with academic rigor.

His experience in the Philippines profoundly shaped Pangalangan’s journey into law and justice during the tumultuous period of the Marcos dictatorship. Growing up in a society grappling with repression and authoritarianism, he witnessed legal structures being manipulated to consolidate power. These early observations left a lasting mark, sparking his interest in the dual nature of law—as both a tool for oppression and a weapon for resistance.

Pangalangan’s resistance took shape in his first law review article, which critically analyzed the regime's legal maneuvers. Reflecting on this era, he describes his activism as part of the anti-dictatorship struggle. “It was both an academic exercise and an act of defiance,” he explains, underscoring the power of intellectual critique to challenge an oppressive system.

This commitment to justice was evident early in his academic journey. Pangalangan began his studies in political science, exploring the interplay of governance and societal change. However, his growing realization of the practical applications of law in confronting authoritarian regimes led him to pivot to legal studies. Inspired partly by his father, who was a law practitioner and educator, Pangalangan deepened his focus on the legal mechanisms that could advance human rights and the rule of law. His participation in the anti-dictatorship movement further cemented his dedication to these ideals.

Despite the challenging times, Pangalangan found moments of hope and recognition. Immediately after graduating, he was invited to join the faculty of his alma mater—a rare honor that underscored his academic promise. “I was the first to be recruited in about 10 years, because [the faculty] had become too snobbish,” he recalls with a touch of humor. This early validation of his work further fueled his resolve to harness the law as a force for accountability, empowerment, and meaningful change.

His pursuit of justice took him to Harvard University, where he earned a Master of Laws and a doctorate. At Harvard, he was exposed to the broader theoretical frameworks of American legal scholarship, which focused on the law in social and historical contexts. This helped him transcend the legalistic traditions of Philippine law and shaped his approach to focus on the intersections of constitutional law, human rights, and international humanitarian law.

These early influences laid the foundation for Pangalangan’s lifelong commitment to using the law to challenge abuses of power, uphold human dignity, and advocate for accountability on both domestic and international stages.

His academic contributions were complemented by his involvement in drafting the Rome Statute, the treaty that established the ICC. “At the time, many considered an international criminal court illusory and unrealistic,” he recalls. Yet, the end of the Cold War and the creation of tribunals to address human rights abuses in Yugoslavia and Rwanda revived the push for a permanent court. Pangalangan’s work on the Rome Statute culminated in his eventual appointment as an ICC judge, a position that required navigating the complexities of international law while maintaining objectivity in the face of atrocities.

This dual perspective—acknowledging the humanity of victims while upholding the rights of the accused—reflects the delicate balance international justice must strike.

As a judge, Pangalangan encountered profound tensions between individual accountability and broader societal healing. He noted that while trials focus on the rights of the accused, they often leave victims seeking reparations and acknowledgment of their suffering. “The irony is that traditionally in a trial, the primary focus is justice for the accused, not necessarily the victims,” he explains. This tension underscores the challenges of using criminal law as a tool for historical truth and reconciliation.

One of the most challenging aspects of Pangalangan’s work as an ICC judge was balancing the emotional weight of victims’ testimonies with the need for objectivity. He describes the heart-wrenching accounts of survivors—women forced into marriages with rebel commanders, children recruited as soldiers, and communities devastated by violence. “It is inevitable that judges see the human side of the cases they hear,” he says. “But the ultimate decision must be based on the law and evidence.”

This dual perspective—acknowledging the humanity of victims while upholding the rights of the accused—reflects the delicate balance international justice must strike. It also underscores the limitations of law in addressing the broader social fissures caused by conflict.

After retiring from the ICC, Pangalangan sought space to reflect and write about the broader implications of his work. The Wilson Center’s emphasis on linking scholarship with policy made it the ideal environment. “The idea of scholarship relevant for policymaking aligns perfectly with my goal of addressing the larger issues that define the success or failure of institutions like the ICC,” he says.

At the Wilson Center, he has revisited topics such as the legitimacy of international tribunals and the effective application of global norms.

Pangalangan’s current research at the Wilson Center examines the “power and limits of international criminal law,” and emphasizes the need for realistic expectations. “Courts are dependent on available evidence, which is often incomplete or one-sided, often hostage to the cooperation of states,” he says. Pangalangan also cautions against being overly reliant on courts to heal societal divisions or comprehensively document history. “When we do that, we ironically make courts even more vulnerable to the judgment of politics and history.”

Pangalangan emphasizes the importance of consistency in applying international legal norms, particularly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the ongoing crises in the Middle East. Reflecting on Ukraine, he noted how the conflict tested the principle of the non-use of force, a cornerstone of the UN Charter. “The Russian invasion was a brazen violation with a very thin legal cover,” he observed. However, he warned that condemning Russia while ignoring similar violations elsewhere undermines the credibility of the international legal system.

In the Middle East, Pangalangan highlighted the devastating human toll of conflicts, such as the displacement of communities and the erosion of human rights. “The law’s role here,” he explained, “is not just to document atrocities but to minimize the human cost of war, ensuring civilians are protected under international humanitarian law.” While international law may not prevent conflict, Pangalangan believes it plays a vital role in holding perpetrators accountable and safeguarding human dignity amidst chaos.

Through his work at the ICC, his scholarship, and his teaching, Pangalangan is considered a leading voice in international law. His ability to bridge academic theory with practical application ensures that his insights remain relevant for policymakers and legal practitioners.

As he continues his fellowship at the Wilson Center, Pangalangan is dedicated to advancing a deeper understanding of the complexities of international justice, advocating for both its power and its limitations. He underscores that while international courts may not always achieve immediate deterrence or reconciliation, they play a vital role in documenting atrocities and providing a framework for understanding conflicts. “The records we produce today are not just for the present but for future generations, offering an impartial account that can inform history and guide future efforts toward justice,” he explains.

“At its core, international justice is about holding power to account and giving voice to those who have suffered in silence,” Pangalangan reflects. “The law may not heal all wounds, but it provides a framework for dignity, accountability, and hope in the face of human tragedy.”

Author

Explore More in Scholar & Alumni Spotlight

Browse Scholar & Alumni Spotlight

Olufemi Vaughan: Shaping Governance Through Scholarship and Dialogue