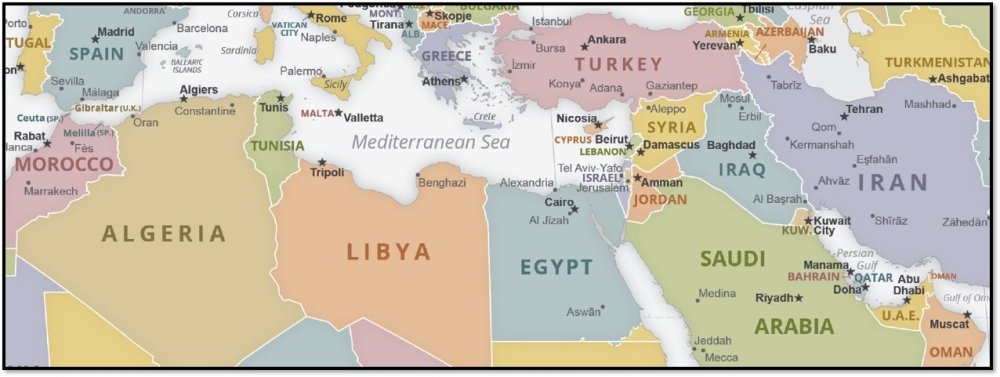

After a half century, Islamism has become the single most disruptive force—both politically and militarily—in the Middle East. It evolved from cells of political activists in the 1970s into mass movements and, for the first time, as a governing force in the late 20th century. Both Sunni and Shiites turned to their faith amid the failure of monarchies and autocracies to deliver political freedoms, economic benefits, stability, or security since the wave of independence from colonial powers began in the mid-20th century. “Islam is the solution” became a common refrain echoed by multiple movements. Islamist political parties competed in democratic elections in North Africa, the Levant, and the Gulf. Meanwhile, diverse militant movements—from Morocco to Egypt, from Lebanon across to the Gulf—turned to hostage-taking and suicide bombs against diplomatic, military and civilian targets to enhance their impact.

Islamism expanded in the 21st century—in vastly different ways. Parties willing to run won democratic elections in Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, Iraq, Turkey, and the Palestinian Authority. Some were short-lived in power. Militants simultaneously became more brazen, whatever the large loss of life among their constituents or the vast destruction. The map of the Middle East changed after huge chunks of territory were seized from Iraq and Syria to create the first modern caliphate. Militias also triggered two devastating wars with Israel in 2006 and 2023.

Six Phases

Islamism has played out through six phases across two dozen countries. The first turning point was the 1973 war, when Arabs fought for the first time in the name of Islam. Egyptian President Anwar Sadat code-named Egypt’s invasion of Israel “Operation Badr” after the Prophet Mohammed’s first victory in 623 AD. In 1979, twin crises—the Iranian revolution ending more than two millennia of dynastic rule, and the bloody, two-week seizure of Saudi Arabia’s Grand Mosque by a fundamentalist cell—reflected the rejection of modernization by both Shiites and Sunnis based on Western ways. They sought a more culturally credible form of governance.

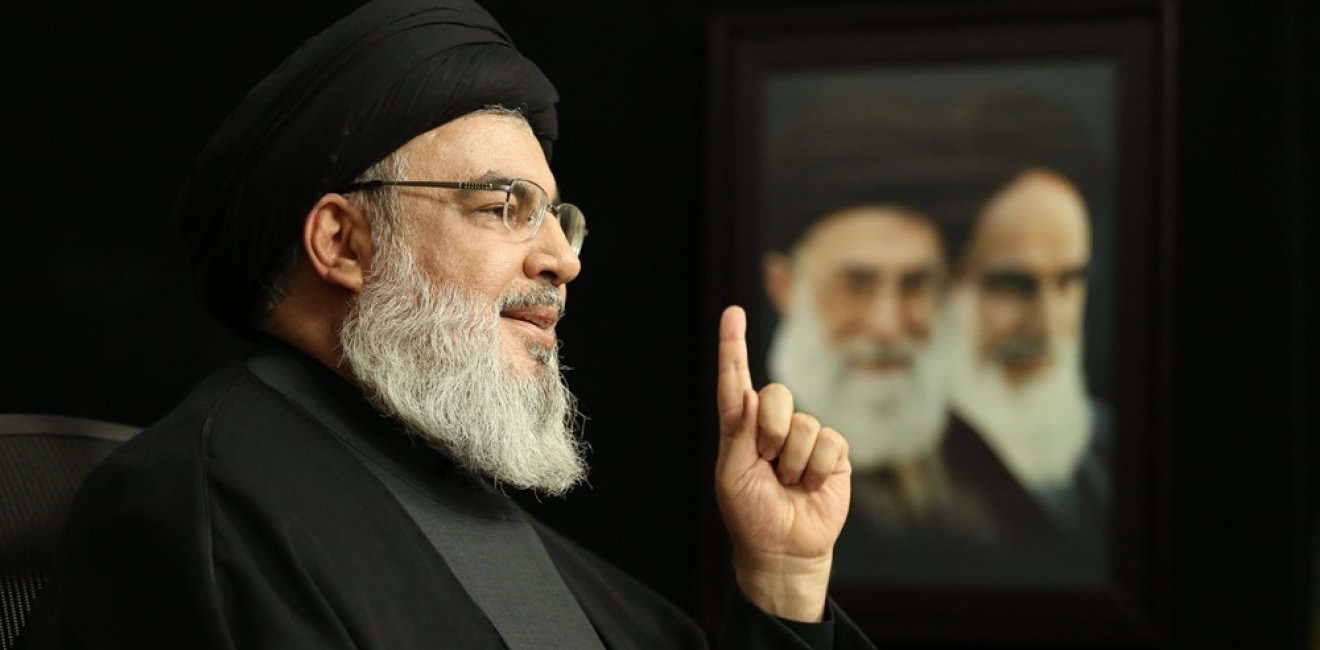

The second turning point—for both parties and militias—was in the 1980s. Branches of the Muslim Brotherhood, a Sunni movement, ran in parliamentary elections in Egypt and Jordan and won seats. In Egypt, the group ran under the cover of other opposition parties. But militant Islam also accelerated, especially during the first modern jihad against the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. Thousands of Sunnis, mainly from the Gulf states, joined the decade-long campaign. The so-called “Afghan Arabs” later transferred their skills and experience to other countries. Among them was Osama bin Laden, the Saudi founder of al Qaeda. In Lebanon, Hezbollah mobilized cells of Shiites in the early 1980s for the first suicide bombings of Israeli troops as well as U.S. Marine peacekeepers and two American embassies in Beirut, and on multiple embassies and business sites in Kuwait. By the end of the decade, Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza had launched the Intifada against Israel, which in turn spawned Hamas and further empowered Palestinian Islamic Jihad. Both called for the destruction of Israel and the creation of a state governed by strict Islamic law.

The third phase was in the 1990s. Political Islam gained ground in Algeria, when the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) defeated more than 50 parties in the country’s first fully democratic election. The final runoff in 1991 was preempted by a military coup that outlawed FIS, imprisoned its leaders, and triggered a more extremist movement that fought government troops for a decade. More than 100,000 Algerians died during the civil war. In Lebanon, Hezbollah evolved from an exclusively clandestine terrorist movement into a registered political party that ran for office in 1992—and won seats.

But militant Islamist groups also became more ambitious in the 1990s. Hamas formed its military wing dubbed the Izz ad Din al Qassam Brigades, named after a Palestinian leader who had fought British occupation in the 1930s. The first suicide attack by Hamas on Israel, in 1993, was near the Mehola settlement in the West Bank. Al Qaeda operatives attacked the World Trade Center in 1993, the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998, and the USS Cole off the coast of Yemen in 2000.

The beginning of the fourth phase was marked by brazen al Qaeda attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on Sept. 11, 2001. The hijacking of four commercial airlines and bombings of the U.S. financial hub and capital were unprecedented—and a boon to the jihadi movement. Over the next decade, al Qaeda spawned affiliates in North Africa, Syria, the Arabian peninsula, South Asia, and East Africa. But two U.S. wars—launched against the Taliban in Afghanistan, in 2001, and President Saddam Hussein in Iraq, in 2003—also further spurred Islamist movements and spawned new ones. From Lebanon, Hezbollah ran a daring operation into Israel—to increase pressure for the release of Lebanese and Palestinian prisoners—that triggered a 34-day war. It was then Israel’s longest war Israel, and it was fought to a stalemate that the Party of God claimed as a political victory. It recouped, rebuilt and ended up with even more weaponry.

The fifth phase was marked by the changing political landscape after the 2011 Arab Spring ousted leaders in Egypt, Libya, Tunisia and Yemen, in turn opening the way for long-banned Islamist movements to run for office. They experienced unprecedented peaks but also unprecedented lows. Ennahda in Tunisia and the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice party in Egypt both won pluralities in national elections. Mohammad Morsi of the Brotherhood won the presidency in Egypt, albeit for only a year before the movement was toppled and outlawed in a military coup.

But growing instability, politically and economically, also paved the way for the mushrooming Islamic State—an offshoot of al Qaeda with more ruthless tactics—to recruit some 60,000 fighters from throughout the world. The Sunni jihadis seized a third of Iraq and Syria to form the first modern caliphate in 2014. It took a U.S.-led coalition of 83 countries and partners five years to force ISIS to retreat from Iraq in 2017 and from Syria in 2019. But by then, ISIS had franchises still active on three continents.

The sixth phase, in the 2020s, initially appeared to reflect the decline of both political and militant Islamism. Ennahda had become the largest party in Tunisia’s parliament in 2019 elections. But, amid public protests, the president arrested top officials and closed the party’s offices in 2022, then imprisoned its leader in 2023. The two-year global pandemic also complicated recruiting and logistics for militant groups. Yet underlying grievances, built over decades, went unresolved. In 2023, Hamas launched an unprecedented attack—in scope, tactics and casualties—across southern Israel. During the war, both Israel and the Palestinian group faced their greatest existential military challenges.

Defining Factors

Islamism covered a wide spectrum that crystalized in the 1990s. “Islamism and jihadism were distinct. Islamists participated in elections, worked within the nation-state framework, and didn’t typically excommunicate other Muslims,” Alex Thurston, a political scientist at the University of Cincinnati, told The Islamists. They accepted territorial boundaries. “Jihadists, on the other hand, had a highly exclusivist and violent revolutionary outlook that made them a different species altogether.” They generally supported the overthrow of modern states and rejected the international order. Islamists and jihadists operated in “fundamentally different frameworks,” Thurston said.

Even militant jihadis differed. Al Qaeda, founded by bin Laden, argued that his movement had to first convert Muslims to its vision of an Islamic state and create ripe conditions for a modern caliphate to survive long-term. The Islamic State, initially an offshoot that later broke away, argued that it had to create a caliphate first and then force both Muslims and members of other faiths to accept it—under penalty of death. Among Palestinians, Hamas and Islamic Jihad both sought to eliminate Israel. But Hamas was willing to run in elections and participate in governance, while PIJ was only interested in a violent and perpetual state of war with Israel. Hamas even had its own rival factions—among leaders in Gaza, the diaspora in Lebanese refugee camps and political leaders based in Qatar.

Alliances also varied, especially among Shiites and Sunnis. Iran generated, armed, trained and financed allies—Hezbollah in Lebanon, several groups of varying size in Iraq that operated under the umbrella of the Popular Mobilization Forces, Houthis in Yemen, and others. Most were Shiite, with the notable exceptions of Hamas and PIJ. Iran’s proxies operated in the so-called “Axis of Resistance” that acted on behalf of Iran in varying degrees but catered to their local constituencies. They had diverse local agendas. Al Qaeda was a Sunni movement with branches in North Africa’s Magreb, the Arabian Peninsula, and south Asia. They pledged fealty to the original core of leaders but operated more independently and locally, especially since the deaths of bin Laden in 2011 and Ayman al Zawahiri in 2022 in U.S. military operations.

Failures

Political Islam witnessed a shift during its sixth phase. Islamist political parties were “far less relevant than they were a decade ago,” Sarah Yerkes, a fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, told The Islamists. They were “steadily losing support across the Middle East and North Africa.” They needed to “figure out how to both operate in increasingly authoritarian contexts and closed spaces as well as how to re-capture public support in a region where political parties have lost the trust of the people.” In general, Islamists were less relevant today than they were a decade ago because “they have often been coopted by the authoritarian regimes,” she said. Unable or unwilling to make progress on their political promises, they increasingly lost credibility among followers and voters.

In 2022-23, movements promoting Islamic values in society through the political process suffered “severe setbacks” in Tunisia and in Palestine, Nathan Brown, a political scientist at George Washington University, told The Islamists. Tunisia’s crackdown on Ennahda and the rise of presidential authoritarianism “shut the political path” and left “no clear path back” for a peaceful party. In Gaza, the military wing of Hamas “plunged the movement into a full confrontation with Israel,” Brown added. Hamas won the majority of seats in the last Palestinian election in 2006. Now, “elections will not be at the center or even periphery of Palestinian politics for a while.”

Political trends globally, with the rise of populism and conservatism, also shifted the momentum away from liberal and progressive movements, which took “the steam out of Islamist groups,” Yerkes said. Parties based on giving religion a larger profile in the political sphere were “not able to gain the same levels of public support” they once had.

The future

The prospects for Islamism—both political and military—were deeply impacted by the war between Hamas and Israel. The conflict “elicited near-universal praise from militant Islamist groups” for Hamas, among both Sunnis and Shiites, Katherine Zimmerman, a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, told The Islamists. Groups called on Palestinians to “seize the moment to rise up” against Israel and the United States, especially as US aircraft carriers, warplanes and forces flowed into the region. One major exception was the Islamic State, which warned against cooperation with Hamas. Its fighters had killed Hamas members and supporters in the past.

Overall, however, the violent end of the spectrum appeared “more relevant” than political parties willing to work within traditional state systems at the end of 2023. “The idea that these Islamist movements have moderated has been shattered by the Hamas attack, illustrating that while they might tactically at different points appear to be buying into a broader system, their worldviews are inherently at odds with a liberal democratic order,” Aaron Zelin, a fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, told “The Islamists.”

Yet it became more difficult to “parse” the prospects for both political Islamists and groups willing to use violence, Zimmerman said. Jihadis who employed violence have generally had more success than those working through electoral or other political channels. “The Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood was elected to power and ousted shortly thereafter, having eschewed violence,” Zimmerman noted. But the Houthis, Hezbollah, the Taliban, and Hamas had success through the use force, despite facing much stronger adversaries. “What this means,” she noted, “is there seems to be more willingness for Islamist groups to engage across the spectrum using all means at their disposal to achieve their ends.”

The disparate faces of Islamism will also have diverse appeal in different regions, Zelin said. Iran’s Axis of Resistance network will be important in the Levant and the Gulf. The offshoots of the Muslim Brotherhood network will be key in Egypt and Jordan. Al Qaeda will have pull further afield in Africa. And the Islamic State will be most pertinent to Afghanistan and Africa’s Sahel region, he said. Their fates will also all be affected by local, regional and global factors in different ways. So, after a half century of experimenting with the many tactics of change, there was no single algorithm or trajectory for Islamism.

Islamists in Government: 2023

Algeria: In the 2022 elections, the Movement of Society for Peace, a Sunni Islamist party and offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood, won one seat in the 174-member Council of the Nation. It also won 65 seats in the 407-member People’s National Assembly, an increase of 31 seats since the 2017 election.

Bahrain: The Gulf nation banned opposition movements–including al Wefaq, a Shiite party–before the 2018 National Assembly Elections. In 2023, no Islamist parties were represented in the 40-member Council of Representatives, the elected legislative body, or the Consultative Council, the 40-member body appointed by the king.

Egypt: In the 2020 elections, the Nour Party, a conservative Salafi party backed by President Abdel Fattah El Sisi, won seven seats in the 596-member House of Representatives. It also had two seats in the 300-member Senate, both by presidential appointment. Smaller Islamist parties–including Wasat, the Strong Egypt Party, and Authenticity–boycotted the 2020 elections as a “formality for outside appearances.”

The Freedom and Justice Party, the political wing of the Muslim Brotherhood that won the presidency and a parliamentary majority in 2012 elections, was banned from politics after being ousted in a 2013 military coup led by El Sisi, then chief of the armed forces. Former President Mohamed Morsi was tried and sentenced to death, later commuted to life imprisonment, for inciting violence and espionage.

Iran: The 1979 revolution created the Islamic Republic of Iran, a Shiite theocracy and the first modern government to blend Islam and democracy. The new constitution stipulated that all laws had to be based on “Islamic criteria” and gave ultimate authority to a the supreme leader. Several parties—including hardline, centrist and reformist factions—reflected divergent views on whether clerics or elected leaders should have more power.

Iraq: Sairoon, an alliance led by Shiite cleric Moqtada al Sadr, won 73 out of the 329 seats in the 2021 Council of Representatives election. Despite winning a plurality, Sairoon failed to form a governing coalition. Its lawmakers resigned in 2022 to break the deadlock. State of Law, a coalition led by the Shiite Islamist Dawa Party, won 35 seats in the 2021 election. The Fatah Coalition, dominated by Shiite Islamist parties backed by Iran, won 17 seats. The Coalition of the National State Forces, which included the Shiite Islamist Nasr bloc, won four seats. The Haquq Movement, the political wing of the Kataib Hezbollah militia, an Iran-backed Shiite militia, won one seat. The Kurdistan Justice Group, a Sunni Islamist party, won one seat.

Jordan: The Islamic Action Front, long affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood, won five seats in the 130-member House of Representatives in the 2020 election. The Islamic Center Party, which advocated for an Islamic democracy, won five seats. No Islamist parties were represented in the 65-member Senate appointed by the king.

Kuwait: The Islamic Constitutional Movement, an affiliate of the Muslim Brotherhood, won three seats in the 65-member National Assembly in the 2023 election.

Lebanon: Hezbollah’s political wing, the Loyalty to the Resistance Bloc, won 13 seats of the 126 seats in parliament in the 2022 election. It held two cabinet ministries.

Libya: The Muslim Brotherhood won seats in parliamentary elections after the ouster of Moammar Qaddafi in 2012. But amid political and geographic divisions, it converted into an NGO after many its largest branches disbanded.

Morocco: The Justice and Development Party, a Sunni Islamist Party, lost nearly 90 percent of its seats—down from 125 to 13 in the House of Representatives—in the 2021 parliamentary election.

Oman: There were no Islamist parties in Oman, an absolute monarchy.

Palestinian Authority: Hamas, a Sunni Islamist party backed by Iran, won the parliamentary election in 2006 with 76 of 132 seats. In 2007, it ousted Fatah, a rival secular party, from Gaza and ruled the territory largely uncontested. President Mahmoud Abbas, leader of the secular and nationalist Fatah Party, governed in the West Bank. In 2018, the Palestinian Authority dissolved the 2006 Palestinian Legislative Council.

Qatar: There were no Islamist parties in the 45-member Consultative Assembly.

Saudi Arabia: Political parties were outlawed in Saudi Arabia, a country where Sharia is the source of all laws. The 150 members of the seat Consultative Assembly were appointed by the king.

Syria: There were no Islamist parties in the 250-member People’s Assembly. The government has long banned Islamist parties, including the Muslim Brotherhood. In rebel-held Idlib province, Hayat Tahrir al Sham, a former affiliate of al Qaeda, ruled the Salvation Government in northwest Syria.

Tunisia: Ennahda and Al Karama, two Sunni parties, boycotted the 2022 parliamentary elections over frustration with the president’s increasingly autocratic rule. For the first time since the 2011 Jasmine revolution, no Islamist parties had seats in the 161-member Assembly of the Representatives of the People. In 2023, Ennahda founder Rachid Ghannouchi was tried for “plotting against state security” and sentenced to a year in prison.

Turkey: In 2023, the Justice and Development Party, a movement rooted in Islamism and led by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, won 267 seats in the 600-member Grand National Assembly. It allied with the Nationalist Movement Party, which advocated Turkish Islamism and won 50 seats, and the Free Cause Party, a Kurdish Islamist party. which won 4 seats. The Felicity Party and the New Welfare Party, both Islamist parties, joined the opposition in parliament.

United Arab Emirates: Political parties were illegal, so there were no Islamist parties in its 40-member Federal National Council.

Yemen: The Houthis, a rebel movement of Zaydi Shiites and backed by Iran, seized Sanaa, the capital, in September 2014. In November 2016, they formed a government that ruled roughly a third of Yemen’s territory, in which at least 70 percent of the population lived.

Jordanna Yochai, an MA candidate at Columbia University’s School of International & Public Affairs, contributed research.

Authors

The Islamists

Learn more about Hamas and how it relates to similarly aligned organizations throughout the region. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Israel Escalates Attacks in Gaza: What’s Next?

Israel Expands Operations on Multiple Fronts: Perspectives on the Conflict