As the receding ice conditions allow for (relatively) safer navigation along the Arctic’s waterways for longer periods of time and technological progression in the development of smart submarines continues unabatedly, a cable race seems to have begun to take hold in the region; a development that could turn the region’s maritime domain into a critical global data chokepoint. For its part, NATO, which is currently in the midst of fine-tuning its High North strategy, needs to recognise the importance of the region as an emerging global data nerve centre and devise a well-defined plan for the protection of these cables. Failure to do so would jeopardise the Alliance’s air, land and naval operations and/or presence in the region.

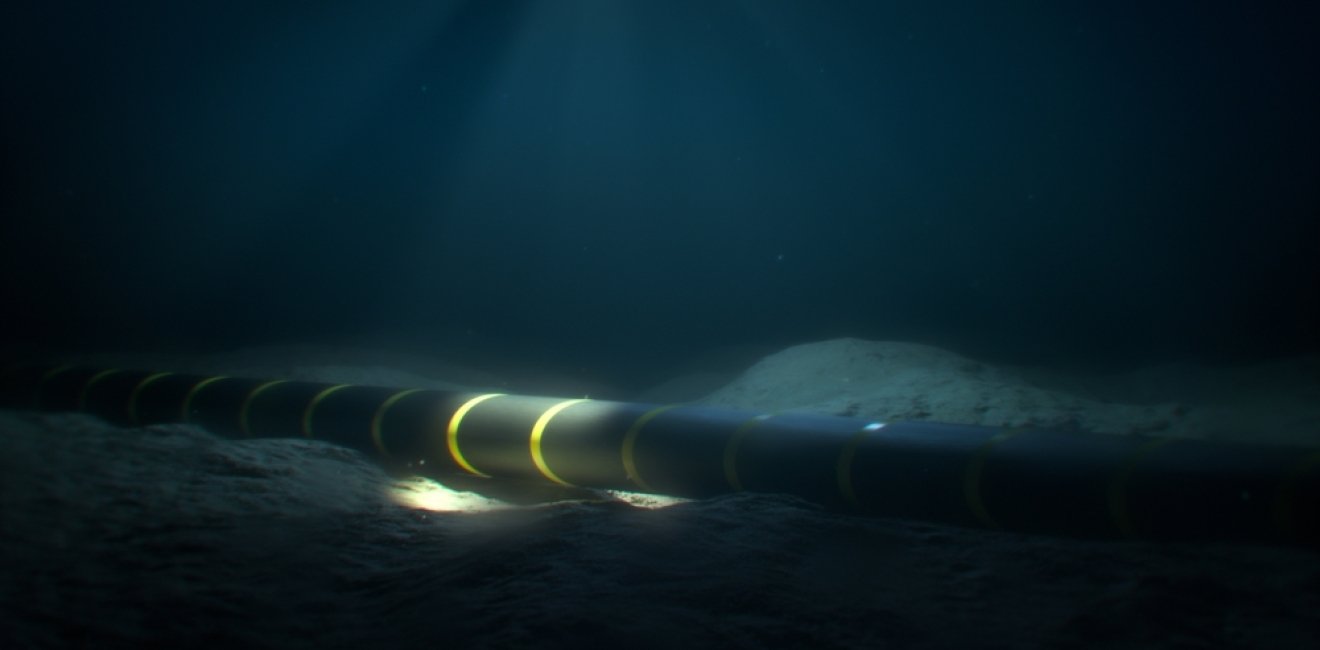

Arctic cables matter for a number of reasons. They are considerably shorter than those that traverse through the established routes like the Suez Canal and the Strait of Malacca. Hence, they tend to substantially increase the speed of data transfer between Europe, Asia and North America. They are also less vulnerable to malfunctioning and/or interruption. Only a handful of states have the required capabilities for carrying out sabotage operations in the Arctic Ocean while the lower volume of vessel’ traffic as well as the Arctic’s own geological specificities reduce the likelihood of damage by either anchors or undersea earthquakes.

Thanks to their ability to accelerate intercontinental data transfers, moreover, operationalisation of these cables would directly benefit industries such as telecommunication, space, and defence. In a sense, subsea cables are nothing short of strategic and intelligence assets that enable countries which control them, or through whose territories they pass, to intercept data, better defend and monitor the global cyberspace, and develop their space industries.

As data reaches strategic parity with energy for economic growth and national security, similarly, sustained access to data will be a critical prerequisite for both the smooth functioning of cross border infrastructural networks and one’s ability to standardise the use of data and digital applications. This is best evident in the case of China’s Digital Silk Road initiative which has prompted Chinese companies to increase their investment in, and ownership of, cellular wireless infrastructures, submarine and terrestrial cables, and data centres within the broader BRI framework

Given the above, it is a matter of prudent decision making for NATO to incorporate the protection of undersea cables into its future Arctic strategy. Put broadly, one can identify two categories of threats in relation to the subsea cables in the Arctic: states abilities to intercept data and/or damage the cables and the ownership structures of the current and future projects. NATO’s efforts at revitalising its political role could receive a much-needed boost if the Alliance positions itself to become the venue of choice for high level talks with regard to the latter. However, it is the former that ought to take the center stage in NATO’s deliberations not least because it better suits its main objective of proactive defence against hybrid threats in the Euro-Atlantic zone.

According to a recent study by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, adversaries such as Russia could be motivated to damage or hack undersea cables in order to gain access to trade and military secrets. This poses a threat on an operational level, especially in the initial phase of a conflict, and tactical level by bringing socio-economic life to a standstill. Adding credibility to such assertions is the fact that Moscow has been steadily expanding its capabilities to tap undersea cables and in fact it is highly suspected to have had a direct role in the recent outage of undersea cables between Svalbard and mainland Norway.

As such, NATO needs to adopt a proactive stance on ensuring the security of Arctic’s future and current cables not least because it is set to become the most dominant security actor in the region once Finland and Sweden membership processes are finalised. Equally important is the fact that there exists no clear legal framework for the usage and repair of (damaged) undersea cables in times of conflict. To this end, NATO must increase its naval assets in the Arctic so it can surveil the region’s waterways better. This could be done as part of its current push for the establishment of an Enhanced Forward Presence in Norway as well as its planned investment for the development and deployment of more high tech assets in its naval operations. More importantly, member states, especially the seven Arctic nations, must facilitate NATO’s participation in repairing the damaged cables by classifying such activities as matters of national security. Doing so has the added advantage of paving the way for the Alliance to contribute to the development of a legal framework for the governance of undersea cables.

Author

Global Europe Program

The Global Europe Program is focused on Europe’s capabilities, and how it engages on critical global issues. We investigate European approaches to critical global issues. We examine Europe’s relations with Russia and Eurasia, China and the Indo-Pacific, the Middle East and Africa. Our initiatives include “Ukraine in Europe”—an examination of what it will take to make Ukraine’s European future a reality. But we also examine the role of NATO, the European Union and the OSCE, Europe’s energy security, transatlantic trade disputes, and challenges to democracy. The Global Europe Program’s staff, scholars-in-residence, and Global Fellows participate in seminars, policy study groups, and international conferences to provide analytical recommendations to policy makers and the media. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Trump Speaks with Putin in Effort to End Russia-Ukraine War

From Partner to Ally: Sweden’s First Year in NATO

“Security, Europe!”: Poland's Rise as NATO's Defense Spending Leader