In a microcosm of the Arab world’s new political spectrum, Morocco now has two rival Islamist powers—one that dominates government and the other that is a banned but popular opposition group. The monarchy, however, still has ultimate control and effective veto power over the political realm. King Mohammed VI tolerated the rise of an Islamist party partly in response to the same kind of demands for reform that have swept North Africa. But Morocco’s experiment also has unique characteristics that are separate from the Arab Spring.

The Justice and Development Party (PJD), which has been the leading Islamist party since 1998, won the right to form a government after winning 27 percent of the vote in the November 2011 parliamentary elections. It is a politically moderate but socially conservative party. The king appointed Abdelilah Benkirane, the party’s general secretary, to form a power-sharing coalition government in January 2012. Members of the politically moderate Islamist party gained control of important ministries, including the ministries of higher education, justice, and foreign affairs.

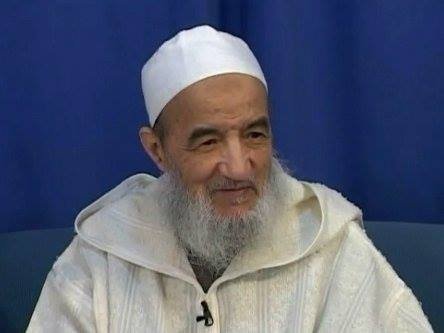

The main Islamist opposition in Morocco is Justice and Charity, a grassroots movement founded in 1987 by Sheikh Abdessalam Yassin, a charismatic leader and member of a Sufi order. Unlike the PJD, Justice and Charity refuses to participate in the political system under conditions it considers illegitimate. It also rejects the dual authority of the king as both head of state and as commander of the faithful, or Amir al Mouminin. Justice and Charity has, in turn, been banned from politics. Despite boasting thousands of followers, its influence has waned since Yassin’s death in December 2012.

The rise of the Justice and Development Party is significant for three reasons. First, the formation of an Islamist government in 2012 was only the second time since independence in 1956 that the monarchy allowed an alternation of power. The king also agreed to reforms that give him less control over government—notably, choosing the prime minister from the party with the largest number of seats in parliament.

Second, an Islamist-led government could erode the monarchy’s tattered religious legitimacy if the PJD projects a socially progressive political agenda and relegates doctrinal disputes to the official religious establishment. Finally, an Islamist government could complicate Morocco’s solid strategic relations with Western powers.

Yet beyond symbolic gestures, the prospects of significant political change under the new government are realistically close to nil. Moroccan Islamists clearly benefited from protests and pressure unleashed by the February 20 movement, a Moroccan version of the Arab protest movements. Subsequent constitutional amendments gave the government more powers. But the PJD’s political ascendance is in no way comparable to the mass electoral victories and popular mandates of Islamists in Egypt and Tunisia.

The PJD was basically domesticated by the palace before it was first allowed to participate in local and legislative elections in 1997. The monarchy’s formal powers and informal networks also remain as strong and extensive as ever. In 2012, the monarchy played a behind-the-scenes role in identifying—and vetoing—cabinet members for sensitive posts. Before the new government was even formed, the king hired key figures from the previous cabinet as counselors, who will have significant executive power and influence.

Finally, the Justice and Development Party has not made a clear commitment to modern universal principles to qualify as the Muslim democratic force it claims to be. On many crucial issues—including women’s rights, cultural openness and diversity, freedom of expression, and rights of non-Arab Amazigh (Berber) people—the PJD is lagging behind both the monarchy and the banned Islamist movement Justice and Charity.

By 2015, the PJD had made little progress pushing forward its political agenda. A series of setbacks – including the loss of its secular coalition partner in parliament and the ouster of Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi – forced the party to give priority to retaining power over mobilizing reforms.

The Beginning

The PJD’s birth took a long political and ideological detour that illustrates the challenge often facing Islamists under authoritarian rule: they can accept political co-optation and risk losing their popular legitimacy, or they can remain in the opposition but risk ideological radicalization. The PJD took the route of moderation and co-optation. It was part of the monarchy’s effort to create a counterweight to the uncompromising Justice and Charity and an increasingly assertive secular civil society.

The PJD’s leadership is generally younger and more collegial than their counterparts in Justice and Charity. Born in 1954, Abdelilah Benkirane was a member of Muslim Youths (Chabiba al Islamiya), a radical clandestine movement established in 1969. The movement’s leader, Abdelkrim Mouti, an inspector of primary education, was influenced by the writings of radical Egyptian Islamist Sayyid Qutb. The group’s original target was universities, which were then under the sway of secular leftists. The PJD’s main objective was to liberate society from jahiliya, which refers to ignorance of divine guidance in pre-Islamic Arabia.

The monarchy’s tolerance of Muslim Youths began to wane after the group’s assassination of a leftist labor leader in 1975 and Iran’s Islamic revolution in 1979. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the government launched a dual strategy of repression and co-optation of Islamist militants. Benkirane broke with the banned Muslim Youths in 1980; he then took small steps to reassure the security apparatus in exchange for help integrating loose Islamist groups into the legal associations.

In the 1990s, two developments aided Benkirane’s project. First, a civil war consumed neighboring Algeria after the military canceled elections that Islamists were poised to sweep in 1992. Second, a radical new clerical movement was highly critical of Morocco’s participation with U.S. forces in the 1990–91 Gulf War to liberate Kuwait after Iraq’s invasion.

In 1992, Benkirane was allowed to establish Reform and Renewal (al Islah wa Tajdid), a group that conspicuously dropped the name of Islam even though it was an Islamic association. It changed its name to the Movement of Unity and Reform (Harakat al Tawhid wal Islah, or MUR) in 1996, after three regional groups joined in. The new movement provided the social and religious backbone of the future political party.

Co-optation

The PJD, officially formed in 1998, was the product of a gradual and lengthy process of negotiations among fragmented Islamic groups and compromises with authorities. Some of those groups sought to influence state policies from within; others worked to reform society from below. But both accepted the principle of working within the confines of a pluralist autocracy.

The division of labor helps to explain why the PJD’s pragmatism—or domestication—did not translate into the ideological transformation expected from a party that claims “Muslim democracy” as a guiding political philosophy. The PJD remains dependent on the socially conservative MUR for leadership, recruitment, and popular support. The majority of the PJD’s General Secretariat holds leadership positions in MUR, a factor that is pivotal to election mobilization. So MUR’s ideological orientation and spheres of influence are powerful, even though the PJD and MUR are organizationally distinct.

Unlike the PJD, the MUR has to respond to poor, urban, and middle-class constituencies that link endemic state corruption and social injustice to moral decay. Beyond general morality, however, MUR lacks a coherent ideology. Its positions are a blend of pragmatism on local issues, the social activism of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, and the reformist spirit of Muslim modernists. This ideological triad is reflected in the MUR’s founding text, al Mithaq, which is written in accessible language with Koranic quotes and in a short political pamphlet with vague references to democracy and freedom of faith.

Yet the differences between the PJD and the MUR should not be exaggerated; both accept the monarchy’s religious attributes and central political role. As of 1997, the PJD and the MUR ran in electoral contests as a single movement.

With the blessing of Moroccan authorities, the MUR was allowed to contest its first elections in 1997 under the name of an already existing party—a virtually empty, inactive political shell called the Popular Democratic and Constitutional Movement. The Islamists changed the party’s name to the PJD in 1998. Since then, the PJD has participated in every local and national election, winning progressively more seats in the parliament and on major urban municipal councils.

The party strategy showed self-restraint by initially running fewer candidates to avoid the “Algerian syndrome,” where Islamists did so well in the 1991 and 1992 elections that the Algerian military canceled the democratic transition. The PJD’s main objective was twofold: First, it wanted to prove that Moroccan Islamists were not a threat to the political system. Second, it sought to prove that Islamists could also be loyal public servants who understood social policies, economic constraints, and the gradual legislative process.

The Moralist Phase

The PJD’s evolution can be divided into two distinct phases: the moralist phase from 1997 to 2003 and the legislative phase from 2004 to 2012. These phases reflect changing dynamics within the parliament, the government, the general public, and other political parties, as well as the changing dynamics between the party and its social wing, the MUR.

During the first phase, the PJD contested two major legislative elections in 1997 and 2002. In the 1997 poll, the party ran only 140 candidates, although it could have competed in all of the 325 contested districts. It won fourteen seats in its first attempt at parliamentary politics.

The outcome was significant on three counts: First, the electoral process was not free or transparent and did not reflect the PJD’s real political weight at the time. Second, the party opted for self-restraint, which meant not winning too many seats. And third, the PJD took seats from older and more experienced parties, including the socialist party, with well-established networks in major cities such as Casablanca.

In the more transparent 2002 elections, the PJD won forty-two seats even though it again voluntarily restricted its participation. The Ministry of the Interior also took away another dozen seats from the PJD for dubious reasons. Again, the Islamists demonstrated that they could not only compete with well-established non-Islamic parties but could also defeat them in major urban centers. The PJD strategy was to present new, young, and educated candidates with moral values.

In the end, however, the PJD’s actual performance once in parliament between 1997 and 2002 was unimpressive. The PJD was crippled by an eagerness to show political moderation and compliance, for which it compensated by showcasing commitment to strict moral values. Instead of taking on the government over substantive political problems or key social and economic policies, PJD deputies focused on restricting the sale of alcohol, “satanic” music, foreign movies, sexual conduct, or inappropriate public behavior. The party’s official newspaper, Attajdid, also opened its columns to well-known Salafi figures who issued highly controversial fatwas.

The Legislative Phase

Moroccan politics was transformed in May 2003, when five suicide bombers struck tourist sites and Jewish sites in Casablanca. Scores of people were killed or injured. A radical Islamist group was responsible, but the attacks put the PJD and its social movement, the MUR, on the defensive. Their leaders were blocked from taking part in mass demonstrations led by civil society, other political parties, and trade unions. The palace, other political players, and some public sector officials implied that the PJD carried a moral responsibility for the attacks. Some even called for the party to be dissolved, while parliament—with the PJD’s endorsement—passed a new law banning political parties that were based on religious, linguistic, or ethnic grounds.

For the PJD, emphasis on social conservatism and moral issues—both often associated with radical causes—was no longer tenable after the 2003 terrorist attacks. The bombings also increased tensions between the party and its movement, although the more pragmatic politicians ultimately gained the upper hand. As a result, the PJD’s parliamentary activities became a priority, but not without a political cost.

The first major test of the PJD’s energized political agenda was the vote in 2003 on a controversial antiterrorism bill. The bill restricted freedom of expression and civil rights and gave the government sweeping powers to arrest and prosecute any person involved in activities interpreted as supporting terrorism. Although reluctant, PJD deputies voted collectively for the bill. Another test was the passage of a highly controversial bill in support of women’s rights. In 2005, the PJD endorsed a new family code, or Mudawana, that gave women more legal rights in matters of marriage, divorce, and child custody.

Yet the PJD’s evolution was not simply maneuvering to survive a hostile environment. PJD representatives also brought new insight into two important pivotal debates: the conflict between national security and civil liberties, and the challenge of reconciling modern women’s rights with Islamic traditions.

In televised parliamentary debates, the PJD blasted the official response to terrorism as a means of silencing independent or opposition voices. On family law, PJD deputies justified their votes to reform laws on three grounds: First, the legislation was approved by religious leaders. Second, the law would help women and families. And third, the law was the product of a democratic process that involved broad consultations with civil society, women’s groups, and political parties.

The PJD parliamentary bloc also became diligent about the legislative process, even circulating its attendance list at a body notorious for absenteeism. It provided its deputies with specialized staff members to help draft and propose bills and technical expertise on policy issues. It also submitted the largest number of oral and written questions to the government.

But the shift from a moralist agenda to legislative activism did not pay off. The PJD was still distrusted by the regime’s hardliners. It was isolated from both governing and opposition parties. And it was circumscribed by rules imposed from the palace. In the end, it had no impact on government policy and passed no bills of its own.

The party’s underperformance in the 2007 legislative elections further exposed the limits of the PJD’s strategy and renewed old tensions between the party and its restless social movement, the MUR. The PJD fielded candidates in ninety-four out of ninety-five contested districts for the vote. Contrary to several poll findings and independent political analyses, however, the party added only four seats—for a total of forty-six seats.

The PJD’s poor showing in 2007 had more to do with low voter turnout than with electoral violations and administrative interference (which were still serious problems). Voter turnout plummeted from 58 percent in 1997 to 51 percent in 2002 and then to 37 percent in 2007, according to the government. And the figures did not reflect the millions of unregistered voters (mainly young city dwellers) and the historically high rate of voided votes (30 percent of ballots in some urban centers).

Just fifteen years after it was founded, the PJD was becoming part of the discredited establishment that it had joined to reform from within. On the eve of the Arab Spring in 2011, the party was struggling to define its role, mission, and strategy. But the popular revolts in Tunisia, Egypt, Yemen, and Libya gave the PJD a new political opportunity. The regime began to use the PJD to stave off the winds of political change that might blow from other parts of the Arab world.

Post-Arab Spring

Morocco’s protest movement was launched by a youth coalition on Feb. 20, 2011 and soon spreading to several major cities. King Mohammad VI responded by announcing a vote in July for constitutional reforms, which included transferring some of his powers to the prime minister. Protests continued into 2012, but the king’s reforms helped mitigate public discontent.

The PJD initially reaped the benefits of the new political opening. In November 2011, the PJD won a plurality in parliamentary elections for the first time, nearly doubling its seats. It formed a coalition with two secular parties, including the nationalist Istiqlal party, which won the second highest number of seats. For the next year, the PJD struggled to work with both conservative Islamists and secular forces, while also avoiding conflict with the monarchy.

In 2013, the PJD faced two major challenges. First, Istiqlal withdrew from the ruling coalition, citing Benkirane’s unwillingness to share power. The PJD became mired in gridlock with its political opponents. Four months later, it formed a new coalition with the secular National Rally of Independents Party.

Second, the ouster of Egyptian President Mohammad Morsi in July put the PJD on the defensive. Tamarrod Maroc – a movement inspired by the anti-Islamist Tamarrod, or “rebel,” movement in Egypt that supported Morsi’s ouster – began calling for Islamist politicians to step down. PJD leaders tried to appease the monarchy, publicly distancing themselves from the Muslim Brotherhood. But they also responded to an outcry from their Islamist supporters by condemning the violent crackdowns on Egypt’s pro-Muslim Brotherhood protesters.

By 2015, the PJD’s political maneuvering allowed the party to remain the largest bloc in government – outlasting Islamists in Egypt, Tunisia and Libya. But its survival came at the expense of addressing key issues like corruption reform. The PJD had done little since 2011 to challenge the monarch’s authority.

Justice and Charity

The PJD’s main Islamist competitor is Justice and Charity, or al Adl wal Ihssan. The movement’s main objective is the establishment of a just society with equal distribution of resources and an accountable government that enforces Islamic law. Beyond utopian references to a state and society modeled after the Prophet Mohammed’s era, the movement does not offer clear and practical alternatives. But it does not promote violence and seemed to be undergoing an ideological transformation after the Arab Spring. For the first time, the movement began to float ideas of a civic state, popular sovereignty, and minority rights.

Because of Justice and Charity’s dogmatic positions, the government has not allowed the movement to integrate into politics as a formal party. Justice and Charity’s activities remain illegal but not exactly clandestine. The movement recruits students at universities, among primary and secondary school instructors, at mosques in marginal urban districts, and in poor neighborhoods.

Despite preaching peaceful change through education and social work, the movement’s leaders and followers continue to face severe repression. After the 2003 bombings, they were targeted during public rallies held to propagate their cause. They were again targeted in 2011, after participating in mass demonstrations sponsored by the February 20 movement.

The mysticism of Yassin—a member of the Zaouia al Boutchichiya Order—might seem ideologically at odds with the movement’s positions, which appear more militant than traditionally spiritual Sufi orders. But in Morocco’s historical context, mystical figures have often risen to advise or even challenge sultans who abused power or neglected governing responsibilities.

Hence, Yassin’s first public appearance in 1974 was an audacious 114-page letter titled “Islam or the Flood” that was addressed to King Hassan II. Presented in the traditional “Mirror for Princes” writing, the public letter exhorted the king to redeem himself if he wanted to save his throne, by following the model of the Prophet’s companions. The letter was sent after two abortive military coups and attempts on the life of the king (in 1971 and 1972). Yassin invited the sovereign to stop ruling like a despot, amassing wealth, oppressing people, and disregarding Islamic teachings. The message was clear: if the sovereign did not heed the advice and reform, he would face the wrath of God and the people (what Yassin called qiyyama, or revolution).

The government responded by holding Yassin without trial in a psychiatric hospital for more than three years. Since his release, the cleric has repeatedly admonished King Hassan II and then his son Mohammed VI—only to again be detained, sentenced to prison, and put under virtual house arrest.

Justice and Charity’s poorly articulated ideology is reflected mainly in the writings of a single charismatic figure, but the movement’s goal is for radical, even republican, change in Morocco. Yet in 2011, Justice and Charity was struggling to define its role. Its refusal either to participate in the political process or to try to overthrow the regime through mass demonstrations raised questions about its long-term effectiveness. It suspended participation in the February 20 activities and criticized the PJD in an open letter for agreeing to lead a government heavily constrained by the palace.

Justice and Charity experienced a major setback in December 2012, when Yassin passed away without leaving a clear successor. The group fragmented, and its message faded from public life. By 2015, the group reportedly still had around 200,000 followers, but its coherence as an organization was severely diminished.

Extremist currents

Hardline Islamist groups have long been active in Morocco. Members of the Moroccan Islamic Combat Group (MICG) – formed in 1998 by Moroccans who trained in Afghanistan – were linked to the Casablanca attacks in 2003 and the Madrid attacks in 2004. By 2015, the MICG was largely defunct. But since 2007, Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) has attempted to forge links with small jihadist groups operating in Morocco.

The rise of ISIS in Iraq and Syria added a new layer to Morocco’s Islamist spectrum. At least 1,500 Moroccans reportedly had joined ISIS as foreign fighters by July 2014 – more than from any other country besides Tunisia and Saudi Arabia.

In a July 2014 video, Moroccan ISIS fighters threatened to launch an attack on Moroccan soil. Unlike AQIM, which opposed Morocco’s secular politicians, ISIS railed against other Islamists, including the PJD and Justice and Charity.

By early 2015, the PJD had avoided widespread accusations of links to ISIS. Justice Minister Mustapha Ramid – a PJD member – even pushed through changes in counterterrorism law in September 2014 that imposed harsher prison sentences for joining armed groups abroad.

The Future

On paper, the 2011 elections gave the Justice and Development Party significant power to help chart the next five years. It won 107 seats out of 395 seats in the Chamber of Deputies. It controlled eleven of thirty-one cabinet posts. Its victory seemed particularly decisive given Morocco’s fragmented political landscape and system of proportional representation, in which no one party or even two parties can claim a majority.

Yet it is hard to be optimistic about the PJD’s political future. Although the constitution was amended to give the prime minister more powers, the king could still veto, formally or informally, any decisions or policies he did not like. The political environment remained depressed, with no specific benchmarks or timetable from the new government to get out of the crisis. The PJD-led government appeared unable to defuse the explosive social climate or pay for promised social services. It did not offer direction on how to energize the economy given the global economic crisis. Its opening statement was little more than a list of good intentions.

On key issues such as democracy, women’s rights, religious freedom, and ethnic groups, the PJD’s statements have remained inconsistent and often contradictory. The PJD has dropped the label “Islamist” and embraced the principles of modern democracy, but the party is drastically different from the Turkish party of the same name, which it claims to emulate. Its documents sometimes vary from what its members of parliament actually say. And leaders may qualify and correct each other when there has been a public outcry about particular statements. Benkirane’s unprepared and corrosive comments about women, the Amazigh minority, and homosexuals produced particular scorn from many civil society groups.

For the majority of Moroccans, dissatisfaction with the electoral process has been reflected in the historically low rates of voter participation and disproportionately high rates of voided votes. The monarchy seemed to respond quickly to the demands of the February 20 movement, fearing the heat of the Arab Spring. But the constitutional amendments announced in March 2011 and legislative elections in November 2011 were widely perceived as futile maneuvers to preempt a local Arab Spring.

The PJD’s lackluster political performance by 2015 suggested that the king’s reforms four years earlier had done little to transform Moroccan politics. Islamists still dominated parliament, but parliament remained shackled by the monarchy. The PJD’s influence remained so limited that it faced the real prospect of being discredited by the time of the next election in 2016.

Abdeslam Maghraoui is associate professor of political science at Duke University and member of the Duke Islamic Studies Center. He is author of Liberalism without Democracy (2006) and a series of papers on the challenge of democratization in the Maghreb. He studies comparative politics of the Middle East and North Africa with a focus on the interplay between culture and politics.

Cameron Glenn, a senior program assistant at the U.S. Institute of Peace, contributed an update of this chapter in early 2015.

Photo credits: Abdelilah Benkirane by Davos World Economic Forum [CC-BY-SA-2.0] via Flickr and Wikimedia Commons; PJD logo via official PJD Facebook page; Abdessalam Yassine via his official Facebook page

The Islamists

Learn more about Hamas and how it relates to similarly aligned organizations throughout the region. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Israel Escalates Attacks in Gaza: What’s Next?

Israel Expands Operations on Multiple Fronts: Perspectives on the Conflict