The U.S.-Mexico border has yet again made an appearance in the political theater of the U.S. presidential campaign, starring in its traditional supporting role as a stock villain character. Though the political dialogue sounds like a re-reading of a script written in the 1990s or early 2000s when Mexican migration peaked, the discussion on the ground in most—but not all—U.S.-Mexico border communities long ago moved on to regional economic development. It is a largely positive discussion that could not be more different than what we are hearing at the national level.

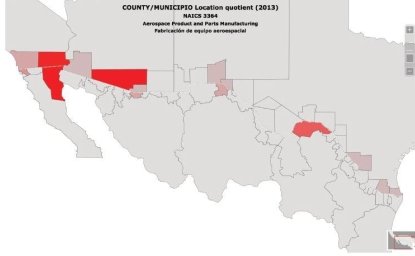

Throughout the border region, local leaders from the public and private sectors are asking themselves how they can form cross-border partnerships to leverage assets in their sister cities and strengthen their local economies. They are looking to create a border that connects the United States to Mexico at least as much as it divides our two nations. A close look at the economic data, however, reveals divergent local economies and major border barriers. In our recent report, Competitive Border Communities: Mapping and Developing U.S.-Mexico Transborder Industries, we found that while advanced manufacturing industries such as aerospace, automotive and medical devices often predominate in Mexican border communities, RV parks, retail and freight transportation are often the most concentrated (and often low-paying) industries in U.S. border communities.

In other words, a close analysis shows a very strong border, one that has thoroughly divided communities in an economic sense despite the family and social ties that bind cross-border communities together. The border currently acts as an obstacle to economic development—particularly for U.S. communities—despite the fact that each side of the border has strengths that could compliment those of the other side.

These communities want much more from the expanding North American economy than simply serving as “pass-through” communities, logistical hubs for continental supply chains. A movement is underway in the border region to engage in binational economic development. Organizations like the Cali-Baja Megaregion, BorderPlex Alliance (El Paso/Ciudad Juárez/New Mexico) and the BiNED (Binational Economic Development) project in the Rio Grande Valley have embraced the notion that the Mexican and U.S. sides of their communities stand stronger together than apart. They are bringing together officials and stakeholders from across the border to jointly court potential investors and to strengthen the local business environment.

While this is an extremely positive development, more work is needed. Based on our research, we recommend that border communities apply the cutting edge tools of cluster-based economic development to their transborder economies. This involves first mapping existing industry clusters (for examples see our mapping tool, this UCSD report, and the official U.S. map) and then capitalizing on the community’s natural strengths. It requires the coming together of local government, business and educational institutions to cooperatively identify and work to remove obstacles to the growth of key clusters.

This type of work is difficult in any city or economic region, but even more so when your city happens to have an international boundary running through the middle of it. Economic development is typically led by local officials and the private sector, but since the border is managed by the federal governments, they must be included as full partners in these efforts. This implies finding ways to better link major bilateral and trilateral discussion of North American competitiveness, like the U.S.-Mexico High Level Economic Dialogue, to the border region stakeholders.

The border, dividing the United States and Mexican economies, may have created divergence in the economic paths of border communities, but at this point rather than lament the division, communities should take advantage of the resulting diversity. Border communities can offer industries a unique value proposition by allowing them to combine the comparative advantages of each country in a production platform situated in a single transborder community.

Another challenge is east-west collaboration along the border. In addition to—or perhaps partly because of—the difficult geography of the region, too often communities along the border have understood themselves to be in constant competition with each other, fighting for scarce federal resources and private investment. Border communities must constantly innovate to adapt the latest economic development strategies to their unique multinational context, but the sharing of best practices is impossible in the absence of communication. A new private-sector driven initiative that brings together economic development organizations along the border is beginning to break down some of the old barriers.

The border region is home to an impressive array of manufacturing, innovation, and transportation assets. Taking full advantage of the region’s strengths implies the border must be reconceived as an asset rather than simply an obstacle. To do so, local and national actors must work together to integrate and coordinate economic development efforts, even if that seems to run counter to the political rhetoric about the border.

This article was originally published on the Mexico Institute's blog on Forbes.com