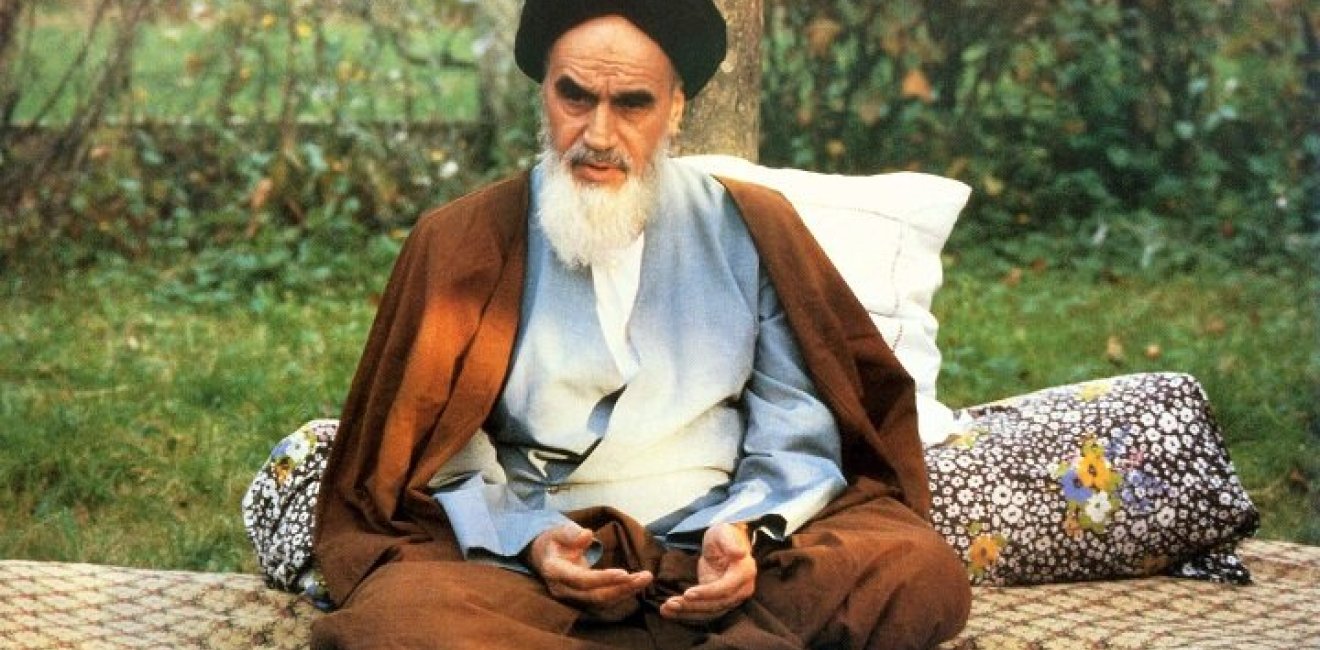

Part 1: Khomeini’s Fatwa on Rushdie

In 1989, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini issued a fatwa condemning Salman Rushdie to death for alleged blasphemy in his novel “The Satanic Verses.”

In 1989, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini issued a fatwa condemning Salman Rushdie to death for alleged blasphemy in his novel “The Satanic Verses.”

Salman Rushdie’s “The Satanic Verses,” which was published in September 1988, was banned in several Muslim countries and eventually triggered violent protests. Iran did nothing for nearly five months. But after six people were killed in Pakistan on Feb. 12, 1989, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini issued a fatwa that condemned Rushdie – along with any editors and publishers of his book in any language – to death. “I call on all valiant Muslims wherever they may be in the world to kill them without delay, so that no one will dare insult the sacred beliefs of Muslims henceforth,” he decreed.

The fatwa rippled across the literary world, spawning attacks against translators and a publisher of foreign editions of Rushdie’s book, and redefined security. In 1991, Ettore Capriolo, the Italian translator of “The Satanic Verses,” was stabbed at his Milan apartment. Days later, the Japanese translator, Hitoshi Igarashi, was stabbed to death at the university near Tokyo where he taught Islamic culture. His murder remains unsolved two decades later. In 1993, William Nygaard, who published Rushdie’s book in Norway, William Nygaard, was shot near his home in Oslo. He, too, survived. In 2018, two days before the 25-year statute of limitations expired, the Norwegian police for the first time charged that the assassination attempt was linked to the Rushdie book. But the assailants have still not been caught.

In Tehran, the fatwa remained a political football for more than three decades—pitting reformers against hardliners. President Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005), a reformist, tried to mend ties with the West during his tenure. The Rushdie case was a key issue in talks with Britain that eventually restored diplomatic ties. “We should think of the Salman Rushdie issue as completely finished,” Khatami told journalists in 1998. A few days later, his foreign minister said that “government disassociates itself from any reward which has been offered in this regard and does not support it.” After nine years of living in secret locations, Rushdie began to appear in public with little or no visible security.

But hardliners continued to encourage action on Khomeini’s fatwa. “The decree is as Imam Khomeini issued,” the current Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, said in 2017 when asked if the fatwa was still binding. Since 2020, hardliners have gained control of all three of Iran’s branches of government. They won a sweeping victory in 2020 parliamentary elections. In 2021, Ebrahim Raisi, a cleric and former prosecutor tied to the 1988 massacre of political prisoners, won the presidency. The judiciary and military had long been controlled by hardliners.

On August 7, 2022 – five days before the Rushdie attack in western New York – a state-controlled website in Tehran republished the fatwa. The decree is “a great and unforgettable fatwa for the Muslims of the world,” Iran Online reported. “Now after 33 years, Salman Rushdie is left with the nightmare of death that will never leave him. He has now become a lesson for all those who harbor illusions of insulting Islam under the pretext of freedom.”

On August 13, 2022, Rushdie was attacked by Hadi Matar, a Lebanese-American, in front of thousands gathered for a lecture on freedom of expression at the Chautauqua Institution in western New York. He was stabbed in the face, neck and abdomen. Matar was arrested on the stage. The next day, he pleaded not guilty to charges of attempted murder and assault. “This was a targeted, unprovoked, pre-planned attack on Mr. Rushdie,” district attorney Jason Schmidt told the court. Matar, a resident of Fairview, New Jersey, was 24 at the time of the attack.

Matar’s social media accounts indicated sympathy for Shiite extremism and Iran’s Revolutionary Guards. Matar’s Facebook profile, which was deleted after the attack, included photos of Khomeini, Khamenei, and General Qassem Soleimani, the commander of Iran’s elite Qods Force who was killed in U.S. drone strike in 2020. A Twitter account in Matar’s name also included pro-Hezbollah images was also suspended. Matar carried a fake New Jersey driver’s license with the name “Hassan Mughniyah,” an alias that may have been culled from Hassan Nasrallah, the Hezbollah secretary general, and Imad Mughniyah, the Hezbollah military commander assassinated in a 2008 car bombing. His parents had immigrated from Yaroun, a stronghold of Hezbollah that is two-thirds Shiite and one-third Christian. Since a trip to Lebanon in 2018, Matar had become more religious, his mother, Silvana Fardos, told media in New Jersey.

The Rushdie attack followed a Justice Department announcement charging a member of the Revolutionary Guards, Shahram Poursafi, for plotting to murder John Bolton, a national security advisor to President Donald Trump. Former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and former Defense Secretary Mark Esper were reportedly also targeted by Iran. All three were under around-the-clock government protection. “We face a concerted threat to America itself, not unconnected threats to random individuals. Iran does not fear U.S. deterrence,” Bolton wrote in The Washington Post.

Learn more about Hamas and how it relates to similarly aligned organizations throughout the region. Read more