Political Violence in Mexico's 2024 Elections: Organized Crime Involvement

This is the second in a series of three articles on political violence in Mexico's 2024 election written by María Calderón.

This is the second in a series of three articles on political violence in Mexico's 2024 election written by María Calderón.

When it comes to an understanding of political violence in Mexico, there is a risk of solely equating it with criminal groups' activities or exclusively attributing it to such groups. However, the political violence phenomenon in Mexico is complex and diverse, with a particular nexus to locally based illicit economies, for which an all-containing approach is insufficient.

About half of the political violence that occurred in Mexico during the 2018 elections was directly attributed to organized crime. During such time, political figures were killed at a rate of one per week.

These numbers support the growing concern about criminal groups' involvement in Mexican politics. Criminal groups have used political violence in several ways: directly manipulating and influencing elections, protecting incumbent candidates with whom they have struck an agreement, killing candidates who are perceived as a threat to their interests, intimidating poll workers, and attacking and stealing voting booths, among others.

The decrease in the profitability of trafficking heroin and cannabis, the legalization of marijuana in many US states, and increased fentanyl usage have forced cartels to recalibrate strategies and markets. Nowadays, criminal groups have partially shifted towards locally based illicit economies, such as oil theft, extortion, kidnapping, and other illegal activities that require control of local territories. All these variables come into play when understanding that criminalized electoral politics is a predominantly local phenomenon in Mexico.

Political violence by criminal groups in Mexico is motivated by multiple factors, including economic interests, political objectives, and vendettas. Criminal organizations often avoid open confrontation when attacking politicians or political candidates, opting for other less visible techniques to minimize the impacts on police and law enforcement agencies, such as corruption.

Installing or co-opting candidates at the municipal level has afforded criminal groups direct influence over the actions of local and state police. Access to intelligence on pending arrests or other operations has also proven beneficial for criminal organizations. Political influence has allowed criminal groups to employ local security forces as appendages of their organizations to detain or kill targets and to protect the transportation of illicit goods. Moreover, criminal organizations have tapped into state finances by coopting government employees.

Criminal groups demand that “investments” in electoral campaigns bestow advantages over competitors or, more clearly, demarcate lines of territorial control. Problems arise when their demands are unmet. There are “paradise municipalities,” which are pacts that work with almost no violence and resistance from the government. However, they are scarce. In some cases, state governors and local politicians prefer to “double-sell the plaza” to several competing criminal groups, perpetuating highly volatile state-criminal arrangements. It is widely known that many politicians' promises are never kept, which, in turn, sparks new waves of violence. In this scenario, criminal groups have turned to direct attacks on politicians, candidates, and police officers. Demonstrations such as burning vehicles and blocking roads or public messages and videos have been employed to inflict reputational damage by attracting harmful press coverage.

Therefore, it is understood that access to the Mexican state is crucial for criminal groups’ survival and expansion. It is generally accepted that only illegal groups with state protection grow. The need for such protection translates into criminal groups threatening competitors’ allies and sabotaging possible arrangements with politicians. There is a particular inclination to do so around elections when new pacts are brokered. In this regard, cartels are forced to change the electoral balance to capture state agents and gain an advantage to control territories and markets.

Mexican politicians or political candidates are identified as rivals when they don't cooperate with organized criminal groups, which then are targeted by way of threats or, in extreme cases, murder. Murders have a particular effect since they send a potent message to political opponents and civil society. There have even been cases of local politicians being killed even hours or days after taking office. Another way, generally unidentified, of pressuring “uncooperative” politicians is through violence to instill fear among voters and in turn, affect voter turnout.

An additional concern is the rapidly increasing involvement of criminal groups in election finances through illicit campaign funding. In Mexico, campaign budgets come along with statutory caps, with an average amount from public and private sources of 333,921 pesos (about 16,650 USD) for municipalities in the 2021 election. Not surprisingly, local candidates view the budget amounts as insufficient, and accepting illegal funding sources from criminal groups hasn´t been uncommon; some campaigns have spent as much as 20 million pesos (500,000 USD).

On the other side, criminal organizations strike local authorities to obtain access to public funds, which they later use to strengthen their territorial presence. This phenomenon, known as the “rent capture strategy,” only functions when the number of resources they can extract exceeds the costs of corrupting public authorities.

When criminal organizations manage to capture local elections effectively, they reap multiple benefits, such as accessibility for transporting illegal drugs, fewer obstacles to money laundering, intelligence gathering, protection from the local police, non-interference in their activities, and even support from the police to combat rival groups. Electoral cycles stimulate violence because it is easier to capture candidates seeking power than sitting politicians who tend to have more extensive state protection.

Mexican cartels see local electoral cycles as an opportunity to attack vulnerable candidates to build subnational criminal governance control, later granting them decision-making influence. As elections threaten the relationships established with politicians and a change in the political status quo, criminal groups continually seek to protect existing political relationships and form new ones.

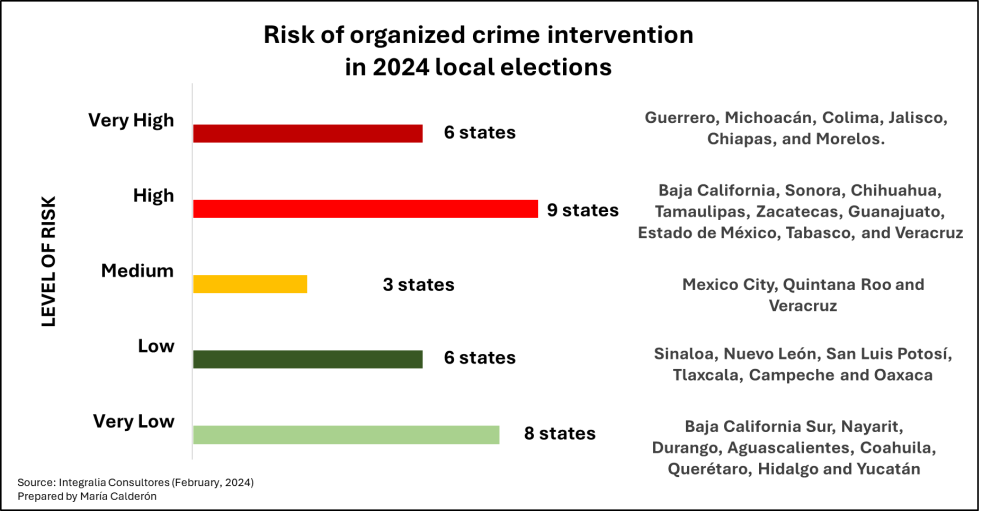

Electoral local dynamics and the consequent risk for criminal groups´ intervention are not homogenous throughout Mexico´s 32 states. Integralia’s risk assessment divides the risk of organized crime intervention in the 2024 local elections into six risk categories: Very High, High, Medium, Low, and Very Low. The states with the highest risk of intervention have i) accumulation of illicit markets, ii) criminal groups in armed conflict, iii) weak rule of law, iv) municipal elections, and v) municipalities considered important to criminal groups.

Regarding the influence of organized crime at the national level, while experts identify the Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación (CJNG) and the Sinaloa Cartel as the main actors with a presence in multiple states, crime dynamics vary by region.

Criminal groups' involvement in politics risks further aggravating the dissimilarities and volatility of dangerous states, creating contrasting realities for Mexicans who are experiencing high levels of crime and violence and, in some cases, polarizing displacements due to criminal groups.

The influence of organized crime in Mexican politics poses an imminent and severe threat to the nation's democratic integrity and stability. The convergence of criminal groups with political structures jeopardizes the fundamental principles of governance, fostering an environment where criminal interests supersede the welfare of citizens. The intertwining of criminal groups and politics compromises the rule of law and undermines the credibility of democratic institutions. This perilous alliance amplifies corruption, perpetuates violence, and erodes public trust, hindering the country's potential for sustainable development.

The dangerous nexus between organized crime and politics demands decisive and vigilant counteraction to safeguard the citizens´ well-being, the democratic fabric of Mexico, and the already declining interest in defending such a system

The Mexico Institute seeks to improve understanding, communication, and cooperation between Mexico and the United States by promoting original research, encouraging public discussion, and proposing policy options for enhancing the bilateral relationship. A binational Advisory Board, chaired by Luis Téllez and Earl Anthony Wayne, oversees the work of the Mexico Institute. Read more