U.S. Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross published an important op-ed (These NAFTA rules are killing our jobs) in the Washington Post this past Friday, September 22nd. In it, he claims to offer a serious analysis to show that the trade deficit with Mexico and Canada and lower U.S. value-added in Mexican and Canadian U.S. imports are proof the United States is losing under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Secretary Ross aims to end the “loose talk” about industrial integration for automobile production in the region.

The problem with the article and the U.S. Department of Commerce paper it is based on is that they cherry pick statistics out of the March 2017, Trade in Value-Added (TiVA) database by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), in an attempt to confirm the Trump’s administration bias that trade deficits are bad and lead to job losses. This wrongheaded approach (the trade deficit with Mexico does not harm the United States) does a growing disservice to the comprehension of the importance of international trade for the economy and further politicizes the issue. More worryingly, it shows civil service officers can be influenced so that their analysis comports with White House views on trade.

Secretary Ross and the Commerce Department he leads make several mistakes in their analysis. The first and more obvious is that they interpret the declining share of North American (Canada, Mexico, and the United States) value-added in total trade as a problem and not as consequence of China’s increasing participation in global markets. Every country and region has seen a declining market share in world trade measured by volume or value-added as China has grown spectacularly in the last 25 years. This has nothing to do with NAFTA. On the contrary, it is precisely because of NAFTA that North American industrial activity has held up and continues to grow; more so now than in the past, in spite of campaign rhetoric.

One of the reasons Asian and Chinese content have gone up so much is related to the dynamism of high tech and electronic products and the increasing use of electronics in autos. All electronics and high-tech imports enter the United States duty free from any country around the world. High tech and electronics represent the largest trade volumes in North America, but they are traded under global rules and not NAFTA.

Furthermore, the United States has negotiated a large number of trade agreements with 18 other countries around the world and these economies have increased their market shares in the United States.

Second, they manipulate the information by basing their analysis solely on percentage participation and thus giving the impression that absolute North American value-added has dropped or that U.S. content has declined; nothing further from the truth. The slice might be smaller in relative terms, but it is much bigger in terms of value, volume, economic activity and, yes, jobs. Ross claims the United States is losing as U.S. content of Mexican exports went from 26 to 16 percent, without pointing out that the pie is many times larger and thus that 16 in 2011 is much more than 26 in 1995. Moreover, there is a large volume of intra-firm auto trade within North America that tends to depress total value reported as the intellectual property is generally accounted for in the commercialization rather than the production phase.

Third, the Secretary dismisses the contribution joint production makes to the North American auto industry. In Europe, German and French brands coproduce with Central Europe to assure competitiveness. In Asia, Japan relies on joint production with Thailand and other South East Asian countries to continue expanding its global presence. In North America, it is precisely thanks to joint production that production and, yes, employment, are growing. From 2009 to 2016, manufacturing jobs in motor vehicles and auto parts in the United States grew 276,000 (41.6 percent) according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics; this while Mexico expanded in terms of capacity and penetration in the regional market. In fact, it is thanks to this deeper integration that companies continue to produce and grow. Without NAFTA, the share of regional and U.S. value-added would be much smaller, including in absolute terms and, in some segments, nonexistent.

Fourth, Secretary Ross deems North American content as too low and argues rules of origin in NAFTA do not work. The numbers in Commerce’s document reject this conclusion. For regional imports from Canada, North American content was 79 percent; from the United States 82 percent and from Mexico 73 percent. These ratios are well above what the overwhelming majority of experts would consider a strict rule of origin. For autos, imports from Canada had a regional content of 71.2 percent and from Mexico 70.5 percent. The case of basic metals is much more interesting, however. North American content of Mexican exports to the United States has gone up from 85.7 percent in 2000 to 91.3 in 2011. The reason is clear: the energy revolution has led to much lower natural gas prices and a much more competitive steel industry; this is why regional value-added is growing and not as a result of more stringent rules of origin. In other words, the Commerce Department document that Secretary Ross is using to argue for new rules of origin is in fact making the opposite argument: North American content is quite high, thank you very much, and, the best way to incorporate more value is, precisely, by promoting a deeper and better integration of the energy market across borders.

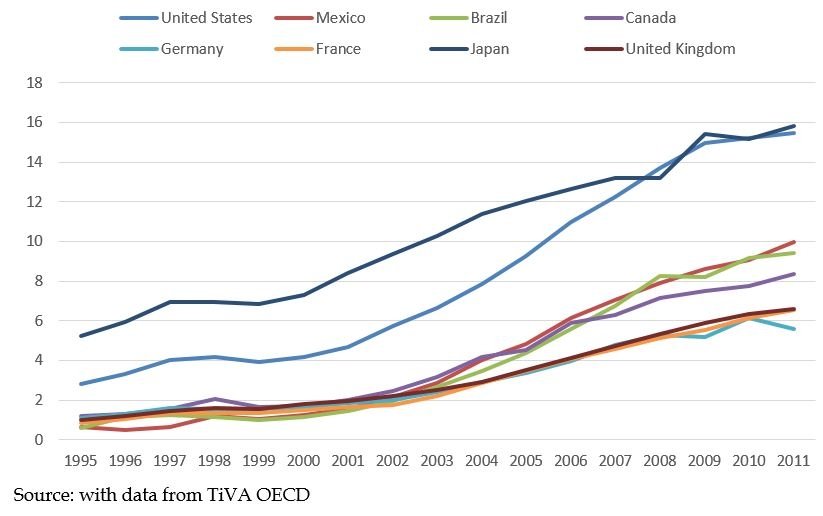

Fifth, the United States and Japan are the two countries that incorporate the highest Chinese value-added in their manufacturing imports, much more than Canada and Mexico and the rest of the world; of course, Commerce’s analysts chose not to dwell on this. The following graph makes the point in stark terms:

Figure 1: Share of Chinese Value-Added in Imports of Manufactured Goods in Selected Countries

Thus, Canada and Mexico are not relying on Chinese value-added in their imports; rather, it is the United States. Needless, to say this has nothing to do with NAFTA.

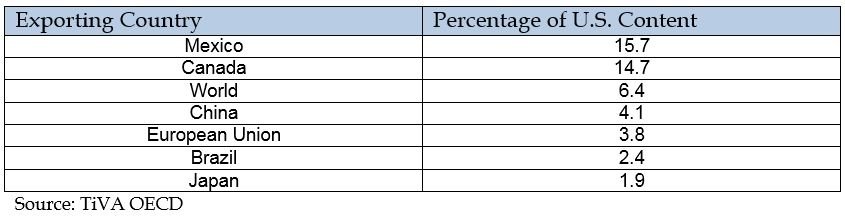

Finally, it is not by accident that Canada and Mexico are the two countries whose exports to the United States incorporate more U.S. value-added by orders of magnitude.

Figure 2: Share of U.S. Value-Added in U.S. Manufactured Imports from Selected Countries

Getting rid of NAFTA would end up lowering regional content to world levels around six percent. This would have catastrophic consequences for U.S., Canadian, and Mexican workers, while Chinese ones would be the primary beneficiaries.

The views expressed here are solely those of the author. This article was also published on the Mexico Institute's blog on Forbes.com.

Author

Managing Director, De La Calle, Madrazo & Mancera and former Undersecretary, Ministry of Economy, Mexico

Mexico Institute

The Mexico Institute seeks to improve understanding, communication, and cooperation between Mexico and the United States by promoting original research, encouraging public discussion, and proposing policy options for enhancing the bilateral relationship. A binational Advisory Board, chaired by Luis Téllez and Earl Anthony Wayne, oversees the work of the Mexico Institute. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

USMCA Resource Page

Water Security at the US-Mexico Border | Part 1: Background