A novel Middle East Women Leaders Index, published by the Middle East Women Initiative, ranked Syria relatively low in women’s representation and leadership in the public sector. The data used (primarily from the World bank and UNDP) for the index covered the status of women in the Syrian government and areas it controls. However, the situation in Syria today is far more complex, almost ten years into the conflict.

In addition to the central Assad-led government, both the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria and various opposition groups control territory in the country— and will likely have some say in its post-war future. Yet their respective policies on women’s rights and representation are vastly different— an important distinction to make in assessing the country’s progress and determining international support.

Leadership and Representation

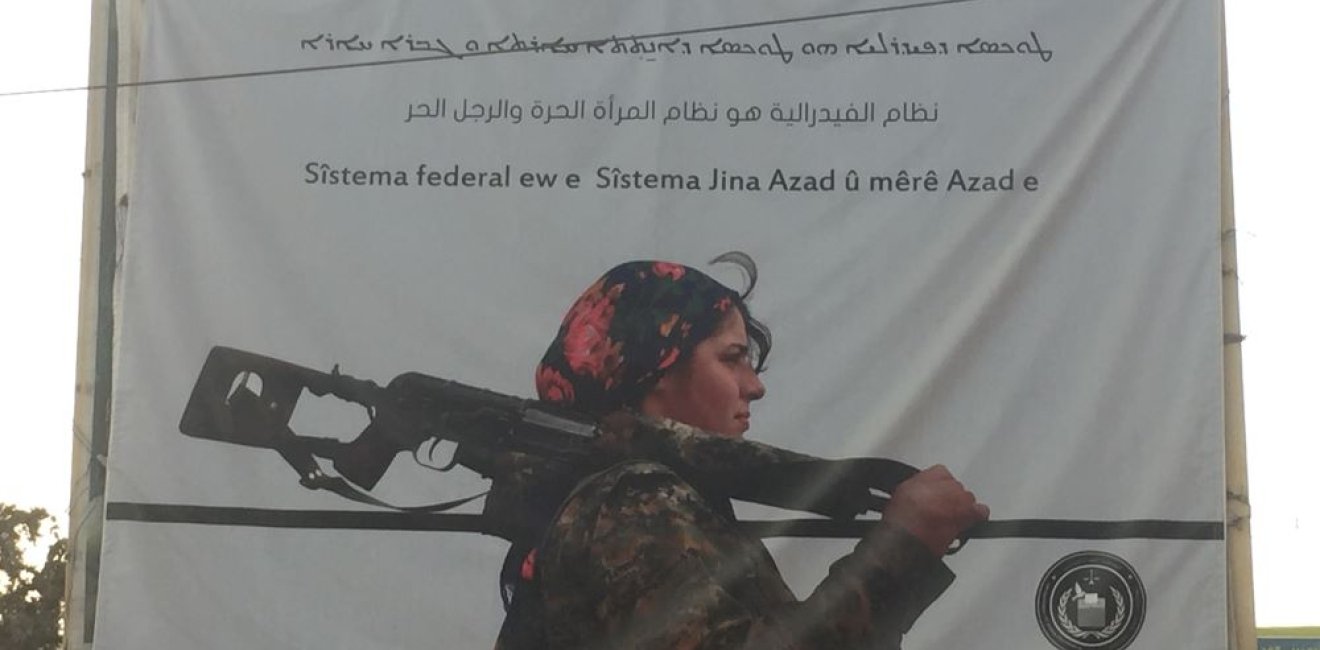

Women in the Autonomous Administration and the Syrian Democratic Forces hold senior leadership roles across policy functions and at all levels of their institutions. Ilham Ahmed, the co-chair of the Syrian Democratic Council, acts as the region’s de facto head of state, speaking before the U.S. Congress and meeting U.S. President Donald Trump last year. Further, the SDF operation to liberate Raqqa from ISIS control was led by a woman commander, Rojda Felat.

With the exception of women-only institutions, every deliberative body operates under a co-chair system, where all leadership positions are held jointly by one woman and one man. Offices and commissions within the Executive Council of the Administration, equivalent to cabinet departments, also use this system.

The Syrian opposition, however, lacks senior female leaders. In 2012, an early conference of the Syrian National Council elected no women to its 41-member decision-making group and the Syrian National Coalition has never had a woman president. In fact, the first woman to serve as the head of any opposition local council was only elected in 2018.

These disparities in senior leadership are reflected across the political structures of each faction. The Autonomous Administration’s constitution mandates that elected bodies and political parties, from the highest levels of the Administration to the smallest neighborhood commune, be made up of at least 40% women. Autonomous women’s organizations, like the Women’s Council of North and East Syria, exist in parallel to every mixed-gender institution, making the percentage of women actually serving in government slightly higher than men. These institutions have the ability to overrule and advise mixed-gender institutions on issues of women’s rights.

The Autonomous Administration’s constitution mandates that elected bodies and political parties, from the highest levels of the Administration to the smallest neighborhood commune, be made up of at least 40% women.

In contrast, a 2016 report from the Syrian Feminist Lobby quoted a study of 105 of the 427 local councils in opposition-held Syria at the time, which found that just 2% of their members were women. Just two women, including the Vice President, serve on the 23-member Political Committee of the Syrian National Coalition, and just 10% of the members of the Coalition’s General Body are women.

Based on this data, the Autonomous Administration would fall into the Middle East Women Leaders Index’s categorization of Ascending Representation— meaning women’s participation and leadership is high at all levels of government and across all policy areas. The report accurately classifies the Syrian government in the category of Aspiring Representation— meaning that women’s participation outside of traditional roles is still low. Despite claiming to represent a new future for the country, the Syrian opposition falls into this category as well.

Legal Status and Protections

New laws implemented by the Autonomous Administration contrast favorably with opposition laws and policies on women’s issues. In North and East Syria, the Women’s Laws address inequities in personal status that existed in Syrian law, and explicitly ban and criminalize child marriages, domestic abuse, and other forms of social inequity and gender-based violence. The region’s constitution states that “men and women are equal in the eyes of the law” and “guarantees the effective realization of equality of women and mandates public institutions to work towards the elimination of gender discrimination.”

Women who face discrimination or violence have significant institutional and social recourse. Women’s NGOs, like the Free Women’s Foundation and the Sara Organization for the Prevention of Violence Against Women, operate openly. Institutions known as “women’s houses” provide community-based mediation for domestic disputes and protection from unsafe home situations. Jinwar, an all-women’s village, is home to women who have lost their husbands in war, experienced sexual violence, and otherwise require support.

In opposition-held regions, no pretense of formal legal equality or legal protections is made. HTS, which controls much of Idlib, excludes women from political bodies and limits their basic freedoms, running gender-segregated schools, enforcing conservative dress codes, and forcing women whose husbands have been killed in the ongoing conflict to move in with a male “guardian.” These policies are enforced by ISIS-like morality police. Activists and civil society organizations that resist them face persecution, and must operate in secret; there is no legal resource for domestic violence, forced marriage, and other gender-based violence under religious law.

In opposition-held regions, no pretense of formal legal equality or legal protections is made. HTS, which controls much of Idlib, excludes women from political bodies and limits their basic freedoms...”

A recent UN report condemned the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army’s treatment of women in areas it has taken over, warning that “by targeting almost every aspect of Kurdish women’s lives…armed groups generated a palpable fear of violence and duress…[which] resulted in an undermining of women’s ability to meaningfully participate and contribute to their community.”

The report stated that these actions— like the assassination of Hevrin Khalaf, a former economy co-minister and then co-chair of the Syria Future Party targeted by Ahrar al-Sharqiya militants in October— constituted a concentrated attempt to “dismantle” the Autonomous Administration’s efforts to advance the status of women.

As the Index notes, laws and policies that regulate the lives of women and girls can either prepare them for political participation and leadership or act as obstacles to it. It is clear that the Autonomous Administration has done the former— while opposition groups have not been willing to implement such protections, and have even gone so far as to seek to force women out of public life altogether.

Why does it matter?

The Autonomous Administration provides a tried and tested blueprint for women’s political empowerment, a policy priority the opposition lacks. The gap in political and social opportunities for women between areas controlled by each faction is shocking. In areas that the SNA has captured from the SDF, like Afrin, Ras al-Ain, and Tel Abyad, the deterioration of women’s rights and basic personal safety is notable.

However, this dynamic has not factored into discussions on the country’s future, or determination of which factions deserve political and diplomatic support. Opposition groups that marginalize women have not faced any consequences for their actions— and the Autonomous Administration’s empowerment of women has not been discussed as a model for the rest of the country or a project that deserves support. Greater understanding of the fundamental differences on this issue, and the unique advances the Autonomous Administration has made, is essential for ensuring that women can play the role they deserve in all aspects of Syria’s future.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect an official position of the Wilson Center.

Author

Middle East Program

The Wilson Center’s Middle East Program serves as a crucial resource for the policymaking community and beyond, providing analyses and research that helps inform US foreign policymaking, stimulates public debate, and expands knowledge about issues in the wider Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Read more

Middle East Women's Initiative

The Middle East Women's Initiative (MEWI) promotes the empowerment of women in the region through an open and inclusive dialogue with women leaders from the Middle East and continuous research. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

MENA360°

How Education Can Empower Young Women in MENA