Tunisia and the Future of Political Islam

An interview with Sarah Yerkes, a senior fellow in Carnegie's Middle East Program.

An interview with Sarah Yerkes, a senior fellow in Carnegie's Middle East Program.

On July 25, 2022, Tunisians voted on a new constitution to grant unchecked power to President Kais Saied, who had been elected to office in 2019 but who then suspended Parliament in 2021. The new charter was approved by 94.6 percent of voters, although the turnout was only 30 percent due to boycotts and widespread apathy.

President Saied’s seizure of power has been a major setback for Ennahda. He has succeeded in demonizing the party. He capitalized on widespread anger at Ennahda by blaming it for much of the failure of Tunisia’s governance since the 2010-2011 Revolution.

At the same time, the constitution is aligned with Ennahda’s values in at least one instance. Saied is a religious and conservative Muslim. The constitution reflects that by going further than anything Ennahda ever proposed. Article Five states that Tunisia is part of the Islamic ummah (nation), and the state alone, within a democratic system, must work to achieve “the goals of pure Islam in preserving life, honor, money, religion, and freedom.” That statement enshrines a bigger role for religion than in the 2014 constitution.

Saied’s next priority is to draft a new electoral law, which he can push through under the new constitution, which allows him to rule by decree until the next parliamentary elections. That law could have serious consequences for Ennahda. The party held the most seats in parliament, 52 out of 217, before Saied’s July 2021 coup. Elections are slated for December 2022. “It is expected that the electoral law that Saied will approve will guarantee his followers victory,” Rached Ghannouchi, the head of Ennahda, said in July 2022, “and exclude certain parties such as the Ennahda movement.”

Even if Saied does not ban Ennahda outright, some of its members could be barred from running for office. Ennahda leaders have often been targets of Saied’s campaign against the opposition, which includes arrests, travel bans, lawsuits, and asset freezes.

Political Islam has become part of mainstream politics in the Arab world. The Arab Spring opened the door to a variety of Islamist parties to compete in elections. Ennahda proved that political Islam could be compatible with democracy. The Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt had early success in elections. The Justice and Development Party (PJD) became dominant in Morocco. They all capitalized on their existing networks and name recognition, whereas most secular parties were brand new. Those Islamist parties are no longer dominant in 2022, but the model is still relevant.

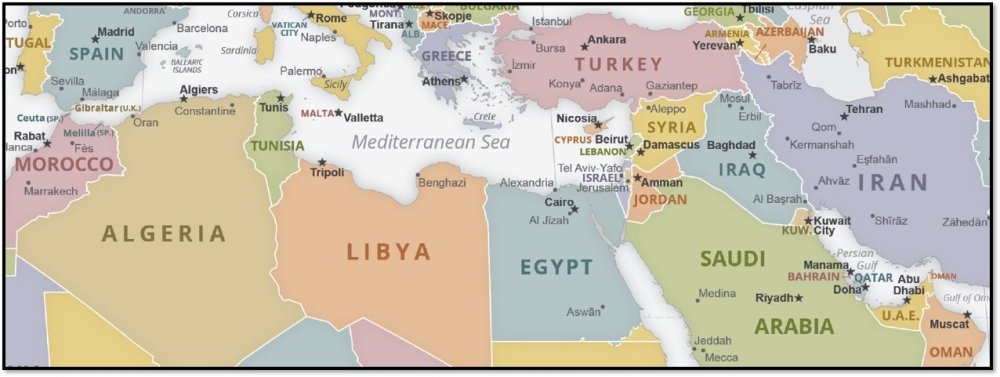

Islamist political parties have continued to participate in elections and governments in Algeria, Jordan, Lebanon and Morocco. Islamist political parties have a future in the region, although the fortunes of individual parties may fluctuate. In Tunisia, Ennahda has been sidelined since Saied suspended parliament in 2021, but it could get a chance to run in the 2022 elections. In Morocco, the PJD suffered a major defeat in the 2021 election, but it could make a comeback.

Lebanon is in a category on its own with a sectarian political system. But it does have a parliament. The main Islamist group is Hezbollah, a Shiite political party and militia that has emerged as one of the country’s most powerful political players. In 2022, Hezbollah and its allies narrowly lost their majority in parliament.

Palestine is also a special case. Hamas is both an Islamist political party and a militia. It won the most seats in parliament in the last election, held in 2006. Before Hamas had a chance to govern, a civil war broke out with rival faction Fatah. Hamas took control of Gaza but was severely weakened in the West Bank. Hamas has continued to rule Gaza virtually uncontested, citing the democratic mandate from 2006.

While in power, Islamist parties have often been the scapegoats of other parties. The opposition naturally has an interest in blaming problems on whoever is in charge, Islamist or not. Islamists, however, have faced a unique challenge from secular parties that have stoked fears about Islamizing society.

Islamists in Egypt have been repressed, at times violently, by security forces since the military ousted President Mohamed Morsi, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, in 2013. After President Abdel Fatteh el Sisi took power, the Brotherhood was banned, its leaders and members were arrested and, in some cases, executed, and its assets were seized.

In Tunisia, authorities have tried to discredit and harass Islamists. Members of Ennahda have been arrested by the police and accused of having ties to terrorist groups or accepting illegal foreign funding.

Islamist political parties are not monoliths. They are prone to the same divides over ideology, strategy and leadership that occur in secular parties. Many have internal processes to deal with debates and rivalries. Ennahda, for example, holds party congresses and competitive internal elections.

The 2013 military coup in Egypt against Morsi, however, forced Islamist groups to pause and consider specific questions about their future. Did they want to aim for the presidency? Did they want to become the biggest parties in parliaments? Or did they want to set more modest goals so as not to become targets of militaries or monarchies? Did they want to prioritize their traditional base or try to appeal to new constituents?

In Tunisia, Ennahda decided to play the political long game by not naming a presidential candidate in the 2014 election (it waited until 2019). Party members also debated over how Islamist the party should be moving forward. In 2016, Ghannouchi decided to rebrand Ennahda as a party of “Muslim Democrats.” This was part of an effort to appeal to a wider base domestically and to bolster Ennahda’s image in the West. Ghannouchi published an essay in Foreign Affairs, “From Political Islam to Muslim Democracy,” that was clearly geared for audiences abroad. The move created a fissure between Ghannouchi’s supporters and others who thought he was not staying true to the party’s identity.

The rebranding effort highlighted brewing tensions over the party leadership. Ghannouchi has headed Ennahda, and its earlier incarnation, since 1981. This continuity has served the party well but has increasingly become a liability. For years, Ghannouchi has had the lowest favorability among Tunisian political figures, according to public opinion polls. He’s not very popular among the general public or his own party membership. His loyalists have encouraged him to stay, but others would prefer to negotiate a graceful exit.

Some Ennahda members have resigned over disagreements with Ghannouchi and his supporters. For example, Hamadi Jebali, who had been secretary general of Ennahda since its founding, resigned in 2015. Some more conservative members resigned and allied with Salafis, ultra-conservative Muslims, to form the Karama Coalition, a new party that won 21 seats in the 2019 election.

Generational tensions have also emerged. Younger members have taken on prominent public roles but have yet to be elevated to higher levels of leadership.

Islamist parties have struggled to distance themselves from jihadi extremists while also trying to win some of their constituents over. Islamist parties prefer that people participate in the political system and try to achieve some of their goals without resorting to violence. But Islamists cannot afford to appear soft on terrorism. In 2013, Ennahda stepped down after extremists assassinated two secular politicians. The general public blamed Ennahda for the lax security situation.

Militant groups are not very active in Tunisia in 2022. Historically, most attacks have been carried out by Tunisians who crossed the Libyan border to train and then returned to Tunisia to carry out their attacks or by militants operating in the mountainous region along the Algerian border. The security situation has improved since the ISIS branch in Libya dissipated in 2017. Tunisia’s counterterrorism forces are also very effective, in large part due to U.S. and European assistance. So, attacks have largely been limited to lone wolves.

The return of Tunisians who fought for ISIS and other militant groups abroad, however, is a looming threat. Tunisia, at one point, was the largest contributor of foreign fighters in the region. At least 5,000 Tunisians traveled to Iraq, Libya and Syria after the Arab Spring. Many are still trying to find their way home, but the authorities have not figured out how to deal with the returnees in terms of incarceration or reintegration. One of the dangers is that men and women awaiting adjudication or who are serving long sentences may be susceptible to radicalization.

The two cases are quite different. In Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood went all in by trying to control parliament and the presidency. It did so well in elections that it got the chance to govern. But once in power it performed poorly and failed to dispel the widespread fear among Egyptians that the Brotherhood would push an Islamist agenda. By the time the military intervened in 2013, many Egyptians thought the country needed saving.

In Tunisia, Ennahda took a more cautious approach than the Brotherhood. It did not run a candidate for the presidency in the first post-revolution election. And it did not win a majority of seats in parliament. So Ennahda formed a troika with two secular parties and ruled by consensus. This started the party down a path of compromise with other political forces. Ennahda never actually implemented Islamist policies, and it never induced the same level of fear among Tunisians about Islamizing the country as in Egypt. Public anger at Ennahda has had more to do with disappointment over the struggling economy and widespread corruption than ideology. Ennahda takes much of the blame since it was the only party consistently playing a major role in governing since 2011.

Most Islamist parties are allowed to operate openly in 2022 across the region. The monarchies in Jordan and Morocco and the ruling regime in Algeria have allowed Islamists to participate in politics, in part to try to appear as if they are democracies. But those parliaments are toothless. And the ruling powers can more easily co-opt and monitor Islamists when they are not operating underground.

Learn more about Hamas and how it relates to similarly aligned organizations throughout the region. Read more