A blog of the Brazil Institute

One month ago, the eyes of the world were fixed on the U.S.-hosted climate summit. The event did bring some notable pledges—including President Joe Biden’s promise to reduce U.S. dependence on fossil fuels. However, the White House-sponsored event overshadowed another significant step in the world’s reckoning with climate change: Latin America’s Escazú Agreement. It became fully operational on April 23, after being ratified by twelve countries—with the notable exception of Brazil.

Across twenty-six articles, the agreement aims to strengthen civil and political rights and improve environmental democracy. It establishes guidelines, mechanisms, and procedures on how to consult populations before making decisions that affect their lives and the quality of their environment. The agreement also expands production and public access to information—which remains poor in Latin America and helps environmental crimes go unpunished.

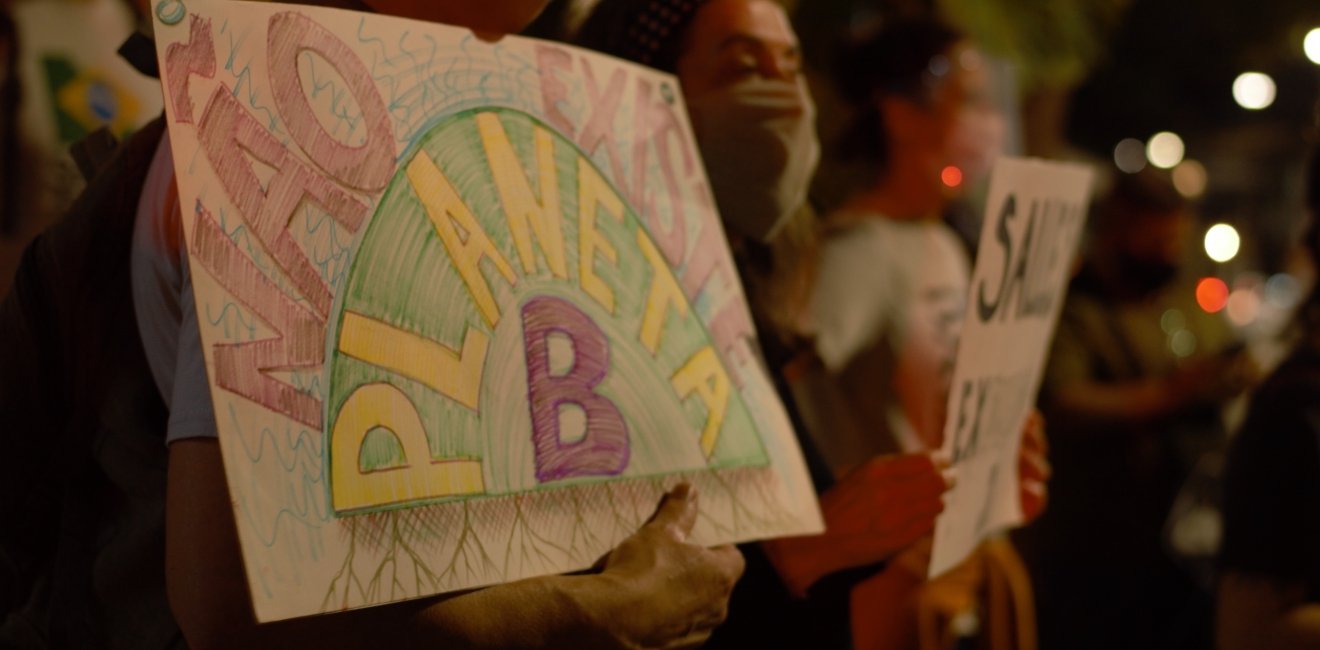

Escazú promotes access to justice by encouraging conflict resolution and obligations to compensate for damages. Crucially for a region such as Latin America, it also establishes protection and cooperation mechanisms for environmental defenders. More climate activists die in Latin America than anywhere in the world.

In its latest report, the NGO Global Witness confirmed 212 killings of environmental activists in 2019—more than two-thirds of which took place in Latin America, with the Amazon region being particularly perilous. Many others faced imprisonment and online smear campaigns because of their work.

Encompassing one of the most biodiverse regions in the world—albeit laden with socio-environmental problems—the Escazú agreement faces major challenges. The treaty seeks not only to protect those who defend the environment, but also to reduce conflict by demanding private companies and governments allow access to information and participate in all projects with a potential environmental impact.

The agreement was first conceived in 2012, and negotiations lasted six years before being finalized in the Costa Rican district of Escazú in 2018. Now, the countries party to the agreement such as Uruguay, Mexico, and Argentina will use its rules as part of their environmental legal framework.

Major Absences could Hinder Escazú Agreement

Six of the world’s ten most dangerous countries for environmental activists are found in Latin America: Brazil, Colombia, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, and Peru. Colombia has topped the list in the last two years, taking first place from Brazil.

Of these nations, however, only Mexico has ratified the Escazú Agreement.

Governments in these countries have cited concerns about sovereignty, legal uncertainty, and commercial interests. Meanwhile, Chile, El Salvador, and Honduras have yet to even sign the document.

Brazil, Chile, and Peru actively participated in negotiations under previous administrations—but these efforts have fallen to the wayside under recent governments.

Not even hosting the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP25) in 2019 could convince Chile’s President Sebastián Piñera to embrace the Escazú Agreement. Meanwhile, in Peru, a lengthy political crisis and the effects of the pandemic have hindered long-term planning.

In Brazil, the situation is more challenging. Far-right President Jair Bolsonaro has indicated that regional relations are not at the top of his agenda, preferring to negotiate Brazil’s climate commitments directly with the United States.

Brazil’s pledge to reduce carbon emissions during the recent Climate Summit was welcomed by the White House, and discussions over Article 6 of the Paris Agreement—which regulates how countries can reduce their emissions using international carbon markets—are making progress behind the scenes, according to sources within the Bolsonaro administration.

However, the notable absence of Brazil and other key countries could hinder the efficacy of the Escazú Agreement, amplifying an existing problem in Latin America: the gulf between environmental laws and outcomes. A report by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) shows that implementation often lags behind environmental legislation, and there is very little data to help policymakers, researchers, and advocates understand and address this implementation gap.

As the Brazilian Report explained in its April 28 edition of the Latin America Weekly newsletter, the number of extreme weather events has risen sharply in Latin America.

By 2050, the World Bank expects almost 2 percent of the region’s population will be displaced due to climate conditions. Moreover, the economic risks are too big to ignore. Insurance provider Swiss Re forecasts economic losses in Brazil of up to 17 percent by 2050 if temperatures rise by 3.2 degrees Celsius.

“There is a lack of resources and qualified personnel in the environmental parts of governments. Coordination with other agencies is a problem and there is a lack of transparency and accountability,” writes the IDB report.

Meanwhile, Uruguay and Costa Rica are positive outliers, with solid indicators for accountability, transparency, combating corruption, and forest and biodiversity conservation.

For environmental activists, the hope is that once the Escazú Agreement is properly implemented, it will lead to more and more signatories and ratifications. “Escazú is the hope that change is possible for Latin America,” said Natalia Gomez Peña, advocacy officer for climate NGO Civicus, speaking to news website Dialogo Chino. “It is a triumph for the communities and civil society.”

Like the content? Subscribe to the Brazilian Report using the discount code BRAZIL21 to get 20 percent off any annual plan.

Author

Brazil Institute

The Brazil Institute—the only country-specific policy institution focused on Brazil in Washington—aims to deepen understanding of Brazil’s complex landscape and strengthen relations between Brazilian and US institutions across all sectors. Read more

Explore More in Brazil Builds

Browse Brazil Builds

They're Still Here: Brazil's unfinished reckoning with military impunity