In 1987, two very different reviews of the state of New York City appeared almost simultaneously. The first was a report issued by an ad hoc Commission on New York in 2000 chaired by Robert F. Wagner Jr., who was the son of the city’s beloved three-term mayor and grandson of a popular New York Senator, and was himself deeply involved in city affairs and a chair of the City Planning Commission. The second review was a special issue of the distinguished leftist journal Dissent edited by author and journalist Jim Sleeper. Although both reviews presented a portrait of what was recognizably the same city, their differences in orientation and interest pointed them in opposite directions. The titles of their work reflect their divergent sensibilities: Wagner’s report captured New York Ascendant, while Sleeper’s journal issue was framed In Search of New York.

Both reports appeared at a turning point in the city’s destiny. The economic disinvestment that was beginning to become noticeable by the end of the 1950s cascaded throughout the 1960s and 1970s; the manufacturing sector collapsed; port facilities and hundreds of critical jobs moved to New Jersey following the containerization revolution in shipping; corporate headquarters fled to the suburbs and beyond; and even the New York Stock Exchange and NBC gave serious consideration to leaving Manhattan for New Jersey. A nadir was reached in a disastrous brush with municipal bankruptcy in 1975, widespread civil breakdown during a 1977 blackout, and excessively publicized violence on the subway and in parks. In the 1980s, a tsunami of violence accompanying a crack cocaine epidemic swept over the city, reaching its peak just as both publications appeared.

In this dire context, Dissent’s contributors told a tale of slow and inexorable urban decline, decay, and death. New York was no longer able to create wealth for the thousands of poor citizens struggling to make their way in the city. As the city became more starkly divided by class, it became less attractive to those who had great wealth. New York was a tough, nasty place full of paranoia, racial hatred, and economic conflict in which residents felt under constant threat.

According to the ad hoc commission’s report, all was not lost. The commission’s members viewed the restructuring of the city’s finances in response to near bankruptcy as having improved New York’s ability to respond to economic change. They found the boosterism of three-term mayor Ed Koch, who held the office between 1978 and 1989, to have lifted civic identity. A New York State tourism campaign, begun in 1977 based on the song “I Love New York” similarly started to transform how New Yorkers and others thought about both the city and its state.

More significantly, according to the commission’s report, the profound changes in international financial markets, reflecting the beginnings of what we now know as globalization—including a newly assertive capitalism unleashed by the Reagan administration, and deregulation of the financial markets—enabled New York to firmly secure its position as a leading global city and world financial center. Technological changes—the opening of the Internet age—reaffirmed New York’s position at the center of global communications; and the maturation of the smart economy expanded its reach beyond Silicon Valley and Boston’s Route 128 corridor, establishing of high-technology industries in New York. Immigration pathways to the United States during the 1960s similarly began to reshape the city as it once more became a magnet for New Americans.

This dynamism, the commission’s report argued, was gaining momentum so that, by 2000, New York would be ascendant once more. The report predicted that the city would regain 300,000 jobs (matching its peak employment in 1969 of 3.8 million) and 400,000 people, growing to 7.5 million by the turn of the millennium. In fact, the city’s population reached a then-all-time high of just over 8 million in the year 2000. This growth was largely driven by immigrants. According to some estimates, more than 3 million immigrants made their way to New York over the past half century, many remaining in the city.

Despite privileging different factors, both Dissent’s and the commission’s reviews identified many similar positive and negative trends. Both accounts lamented the absence of civility in New York life, edginess that both saw as counterproductive for the city and its residents. These hard edges would continue to mar civic life throughout the twentieth century, softening only in the wake of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attack on the World Trade Center. Thereafter, many New Yorkers subsumed whatever differences they had under the shared experience of living in a city under assault.

For the authors of the commission’s New York Ascendant, positive developments were offset by growing income disparities, continued high rates of crime and violence, and a floundering educational system that poorly served both the city’s youth and employers. In spite of their pessimistic outlook, the contributors to Dissent, recognized New York was experiencing a remarkable mixing of different traditions—especially of Hispanic and African cultures—which produced unprecedented creativity on city streets. Both reviews emphasized the importance of the arts, with Dissent highlighting the creativity bubbling up from below and New York Ascendant identifying culture as a draw making the city attractive to what we now call the “creative class.”

In retrospect, the commission was closer to the mark, in that New York once more emerged as one of the world’s preeminent cities. Longtime New Yorkers are not quite confident of this success, seeing what has been described as the “homogenization”—and even the “Disneyfication” or hypergentrification—of their city, while those without abundant means are forced to leave town. Whether this perception is accurate for the city as a whole, there is no doubt that Times Square has been Disneyfied—by Disney itself.

The fate of Times Square –and of the Broadway theater world so central to it--captures the contradictions of the past half-century. In a premature death notice for the Broadway theater, science fiction master Thomas Disch sardonically noted in a 1991 edition of the Atlantic, that bulldozers were gathering to attack the squalor of Times Square by leveling many of the blocks around 42nd Street to replace low life with high-rise towers. This is, in fact, what transpired as mayors Rudy Giuliani (1994–2001) and Michael Bloomberg (2002–13) promoted the conversion of Times Square into a tourist and corporate wonderland embodying broader transformations throughout the city. The Times Square Alliance, established in 1992, lured major corporations to the area and promoted attractions—such as giant LED screens and live television broadcasts—that would create a nonthreatening urban vibe. Bloomberg closed the square to most automobile traffic in 2009, securing the area’s place as a major tourist destination.

Broadway and its theatrical scene have flourished as a tourist attraction, with the number of productions and audiences growing once again. By the 2014–15 season, Broadway was setting new records for the number and value of tickets sold, drawing more than 13 million people paying $1.3 billion. Broadway has become so successful that there is now a shortage of theaters rather than a shortage of productions. Shows are queuing up to find a Broadway venue.

Disch and many others, however, are more concerned about artistic worth than financial profits. From this perspective, shows that are dependent on high-tech wizardry and lushly mounted revivals often do not deserve accolades.

Serious theater has not died, either in New York or in the United States but it has moved, shifting to Off and Off-Off Broadway in New York, and to regional theaters around the country. Broadway benefits from these networks. Shows from Washington, Chicago, and Seattle make their way to Broadway and enrich the New York scene, even as Broadway shows go on tour. There has been a maturation of American theater, in which Broadway is a part of a larger live entertainment industry, with outposts in cities such as Austin, Las Vegas, and Nashville.

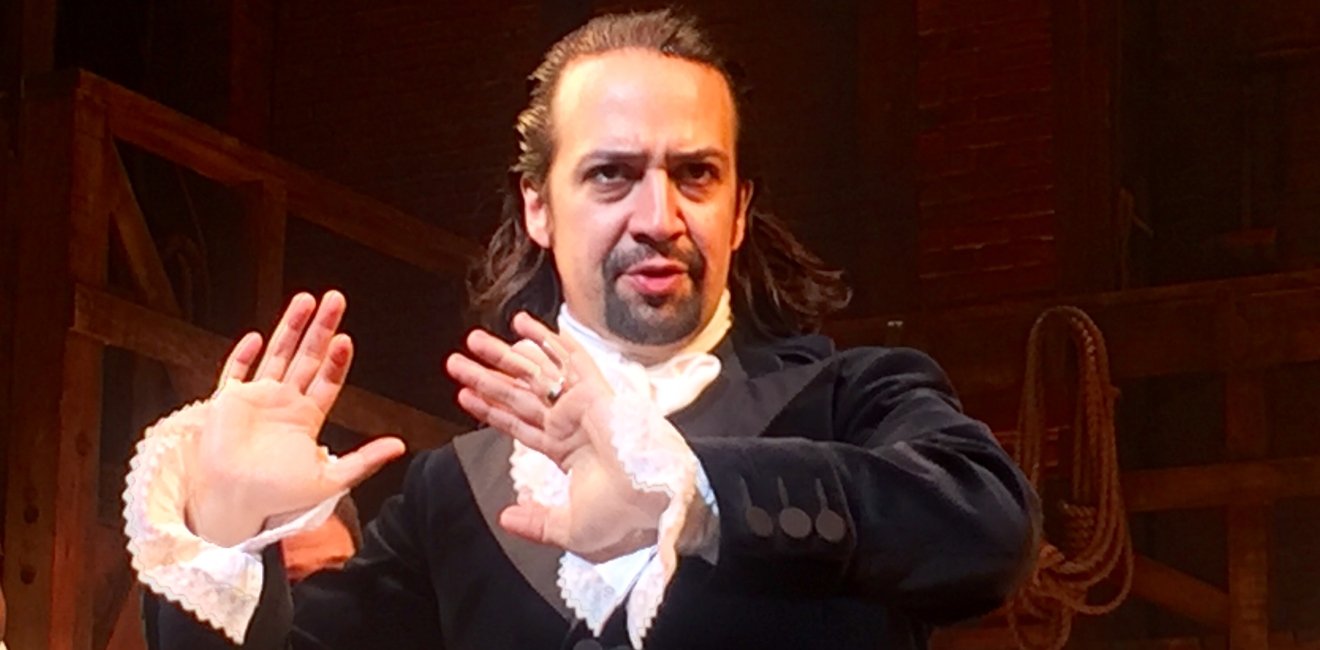

Enduring art forms continually prompt cries of despair over their impending death. For instance, just as some began to write off Broadway as nothing more than light diversion for tourists, Lin-Manuel Miranda came along.

Miranda is a product of the exciting blend of Hispanic and Black cultures celebrated by the authors who contributed to the Dissent issue. Miranda was born in Manhattan of Puerto Rican heritage, and he grew up in Inwood, a blue-collar neighborhood near the island’s northern tip cut off by subway switching yards from downtown. The area evolved from being the home of Jewish and Irish immigrants to the home of Hispanic—often Dominican—newcomers. The basketball legend Kareem Abdul-Jabar grew up a generation before in the same neighborhood; and another generation earlier, a boyish Henry Kissinger scampered around the streets of nearby Washington Heights. This end of Manhattan has long been reserved for the latest arrivals to find their way in a new homeland, often tossing off new cultural permutations in the process.

Miranda graduated from Hunter College High School and went off to idyllic Wesleyan University—a small Connecticut school best known for educating the gentry’s offspring—where he combined the hip-hop of his home turf with a solid grounding in Wesleyan’s more traditional student theater company. While a sophomore at Wesleyan, he began working on a musical based on a book by Quiara Alegría Hudes that told the story of the lives of his generation in the largely Dominican-American neighborhood of Washington Heights. The show, In the Heights, moved from Connecticut to Off-Broadway, and then to a Broadway production in 2008, winning four Tony Awards and a Pulitzer Prize nomination. Miranda—like the Berlins, Kerns, Hammersteins, Rodgers, Harts, and Sondheims before—was setting Broadway on fire by bringing new energy from the ever-evolving life of the city around them.

But In the Heights was just the beginning. In 2015, Miranda’s hip-hop interpretation of Ron Chernow’s authoritative biography of Alexander Hamilton broke every mold on Broadway, starting out with its two-month run at the Public Theater. Hamilton tells the story of one of the country’s most overlooked founding parents through the lens of the generations infused with the sounds of what the city has become.

New York and Broadway—like all human creations and the people who make them—die a bit every day. Simultaneously, they are reborn. No matter how much New York is tamed, the city still bursts forth with elemental human energy. And Broadway theater—like the city that gave it life—continues to confront and define the American experience by enabling newcomers to engage with traditions that have long been in place.

Photo: Steve Jurvetson/flickr (CC BY 2.0)