In September 2015, the United Nations approved 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) intended to shape the global effort to end extreme poverty, fight inequality and injustice, and tackle climate change. Among the 17 goals, one is devoted to the urban condition that is shared by more than half of humanity. Goal 11 calls for action to make cities inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable.

Achieving the SDGs would be difficult under any circumstance; no less so given that the present is an era of growing inequality. Nowhere are exclusion and inequality more apparent than in cities where extreme wealth and poverty co-exists side-by-side. Promoting shared prosperity requires opening up channels for greater mobility of all kinds, including social and economic; but most especially physical. To escape from cycles of poverty and injustice, residents need to be able to move around the city.

What would mobility look like in an inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable city? Some might consider Copenhagen a model: a city designed to promote cycling as the quickest and easiest means for getting around. Traffic lanes are segregated to separate bicycles from cars and pedestrians, cycle tracks are prioritized in service plans so that snow removal takes place on bicycle lanes before car roadways, and traffic lights are adjusted to favor cyclists’ speed. According to some estimates, around two-thirds of all Copenhageners ride bikes. If Copenhagen defines success, than nearly every other city will come to be seen as a failure no matter how much investment is made in multimodal transit options, support of bicycling, and other, perhaps small, interventions to maximize mobility.

Another place to look for innovation is to the US Department of Transportation, which recently launched a Smart City Challenge for mid-sized American cities. According to challenge guidelines, success includes using advanced technologies to “help citizens address safety, mobility, and access to opportunity, sustainability, clean energy, economic vitality, and climate change.”

In thinking about the goal of promoting inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable cities, perhaps there are more meaningful criteria to consider. The simplest test would be to consider whether or not mothers would want their children to grow up in a given community. Meeting that standard depends on ensuring foundations for opportunity and security. Do transportation and mobility have any role in achieving such urban success?

On the one hand, developing and introducing new transportation systems is an engineering problem. But engineers are neither social workers nor politicians. Since large transportation projects are among the most expensive that communities undertake — and have consequences which last several generations — their economic and social value need to be taken into consideration as well. The contours of new transportation projects will shape economic development, social geography, and environmental resilience for decades.

While it is relatively easy to build efficient transport systems which carry the well off from their homes to employment centers, responding to social need through mobility is more complex. The following guidelines help to frame the challenge more clearly. Together, they represent a CARPET of transportation options that envelope the cityscape:

CONTEXT matters. In considering new transportation projects, planners need to have a solid grasp on existing conditions including present transport, employment, and housing patterns. This analysis is already standard. What may be a little unusual is that thought needs to be given to political context over time. In situations involving multiple jurisdictions, for example, secure long-term funding and administrative support must be secured at the outset.

To point to a negative example, the political agreement bringing together several jurisdictions of various sizes and legal status to build the Washington, D.C. metro system did not include provision for permanent secure funding streams. With a jerry-built governance structure and an absence of a secure funding source, the Washington Metro could well have been programmed for failure from the outset. Inept managerial decisions accelerated decline so that a once state-of-the-art system now languishes under neglect and an absence of accountability and transparency as no single authority can be held responsible for the system’s dysfunctions.

On a more positive note we see how in France, employers are taxed for local transportation authorities, providing a reliable funding source. Therefore, funding is secure and with it, accountability mechanisms. Without this structural context in mind we would have difficulty understanding how the Washington and Parisian transit systems achieve such disparate results.

ASK questions. Potential users of any new system — especially the most disadvantaged among them — often know more than experts think they know about how a system must function. There often are differences between actual ridership patterns, projected future transport systems, and real demand. Listen to what is being said to be sure that new systems go where people actually want to go.

In 2004, the Colombian city of Medellin, created a gondola transit system to serve particularly disadvantaged communities. It is the world’s first modern urban aerial cable car transport system, constructed as part of neighborhood upgrading projects, all of which were designed with active input from community members. The system has improved residents’ quality of life, decreased violence in the neighborhood, and addressed spatial inequality as well as reducing emissions and maintaining sustainable mobility.

Meanwhile, planners in Rio de Janeiro moved forward building a similar system, in part based on the Medellin experience. The Teleferico, as it is called, has been controversial from the very beginning. While the system has benefitted some residents — such as elderly and people with disabilities – others in the communities have protested that the system is hardly a substitute for the provision of other basic services such as sanitation, health, and education. Homes and public spaces have been removed for construction of stations. The system has failed to meet expectations not because of any technological flaw, but because planners and officials did not consider the broader social context.

RIGHT SIZE plans. Transportation projects, if they are to be sustained over time, need to conform to the financial and administrative capacities of communities. There is little to be gained by building a cutting-edge system in communities which neither has the funds nor the management capacity to support the system over the long haul. Bankrupting local government undermines potential gains from new systems; while requiring external skilled personnel to operate a system similarly diminishes chances for long-term sustainability.

Oftentimes, building a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system is more manageable and cost effective than rail-based systems, for example. The world’s first BRT in Curitiba has been copied around the world ever since. BRT addresses congestion by designated lanes for buses, consolidating bus stops to reduce their number along a route, and by single payment systems. A BRT can cost up to 50 times less than rail, and it doesn’t take decades for construction.

However, a BRT system is not a sole solution to all transit issues as it may provide insufficient capacity to meet demand. BRT might be an optimal solution in some instances while not in others. Systems must fit with capacity and circumstance to right size a project.

PROTECTED space. Transit systems need to provide citizen security, with adequate resources being provided over the long haul to make them safe and resilient. Public transportation systems such as LA County Metropolitan Transportation Authority and Charlotte Area Transit System have launched safety apps that allow riders to call the police or report a problem quickly and easily, allowing for two-way communication. Riders can submit a photo or video, and choose to report a problem anonymously.

Meanwhile, in all too many cities women, and especially the poor, rely more on public transportation than men and have concerns about personal safety affecting the way they travel. Space is only protected when everyone feels safe.

ENGAGE riders. Reaching out to communities on an on-going basis is important for success. To do so, transit authorities much nurture persistent and long-term relationships with their ridership throughout the lifetime of a system rather than single consultation sessions during the planning process. Rider unions, meaningful public meetings, constant monitoring of ridership patterns and consumer complaints will advance the capacity of management to operate more efficiently going forward.

For example, the Straphangers Campaign within the New York Interest Research Group, has played a leading role over several decades for building a consensus for new investments by engaging riders to rate bus services and rail lines. The straphangers regularly publish rankings of New York’s twenty subway lines and periodically hold other contests such as reports on the 10 best and worst transit events of the year.

By contrast, planners and managers of mass transit in Miami failed to respond to the demand of potential riders for more, better located bus stops as well as for a rail transit connection to the airport (an oversight that took a quarter-of-a-century to alleviate). Public transit trips continue to consume much more time than automobiles despite some of the worst traffic congestion in the hemisphere. Important feedback mechanisms that could have led to improved service remain inadequate for the task of continuously informing decision-making.

TRACTABILITY in the face of change. Adaptability to new realities moving forward is important in sustaining mobility in an urban system. Transportation projects are designed to operate for decades during which time any number of political, economic, social, and technological changes will take place. Systems should be designed to respond to those changes.

The Paris Metro started out as a classic urban system operating within the administrative boundaries of the city. As Paris expanded beyond city limits, planners began thinking in regional terms. The RER-Reseau Express Regional is operated jointly by Paris Metro operator RATP and national rail operator SNCF. It connects Paris and suburbs; running underground like metro in Paris, functioning outside the city as a ground- level commuter rail, and operating with a single fare structure.

The Toronto subway system was constantly ranked among the best in North America a half-century ago. Lacking the political will to initiate the construction of new lines, authorities relied increasingly on a system that failed to serve growing numbers of the metropolitan region’s residents, degrading service on what once had been a gold standard for transit systems.

Collectively, the sensibilities reflected by a CARPET for transportation policies – CONTEXT, ASK,RIGHT SIZE, PROTECTED, ENGAGE, TRACTABILITY – create the milieu in which transportation policies can promote the inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable cities embedded in UN Sustainable Development Goal number 11. Together, they help insure that mobility can be maximized to address inequality and marginalization.

The author would like to thank Wilson Center intern Marina Kurokawa for her assistance in the preparation of these remarks.

To read the original article please click here.

Author

Former Wilson Center Vice President for Programs (2014-2017); Director of the Comparative Urban Studies Program/Urban Sustainability Laboratory (1992-2017); Director of the Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies (1989-2012) and Director of the Program on Global Sustainability and Resilience (2012-2014)

Urban Sustainability Laboratory

Since 1991, the Urban Sustainability Laboratory has advanced solutions to urban challenges—such as poverty, exclusion, insecurity, and environmental degradation—by promoting evidence-based research to support sustainable, equitable and peaceful cities. Read more

Explore More in Building Inclusive and Livable Cities

Browse Building Inclusive and Livable Cities

Hometown D.C.: America's Secret Music City

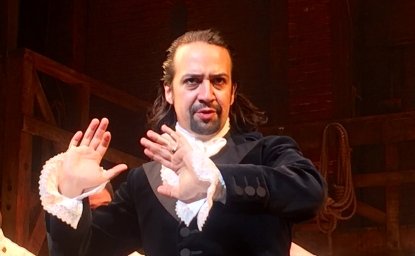

Bringing New York to the Broadway Stage

10 Steps to a More Genuine DC Experience