A blog of the Latin America Program

Chile’s Blind Spot

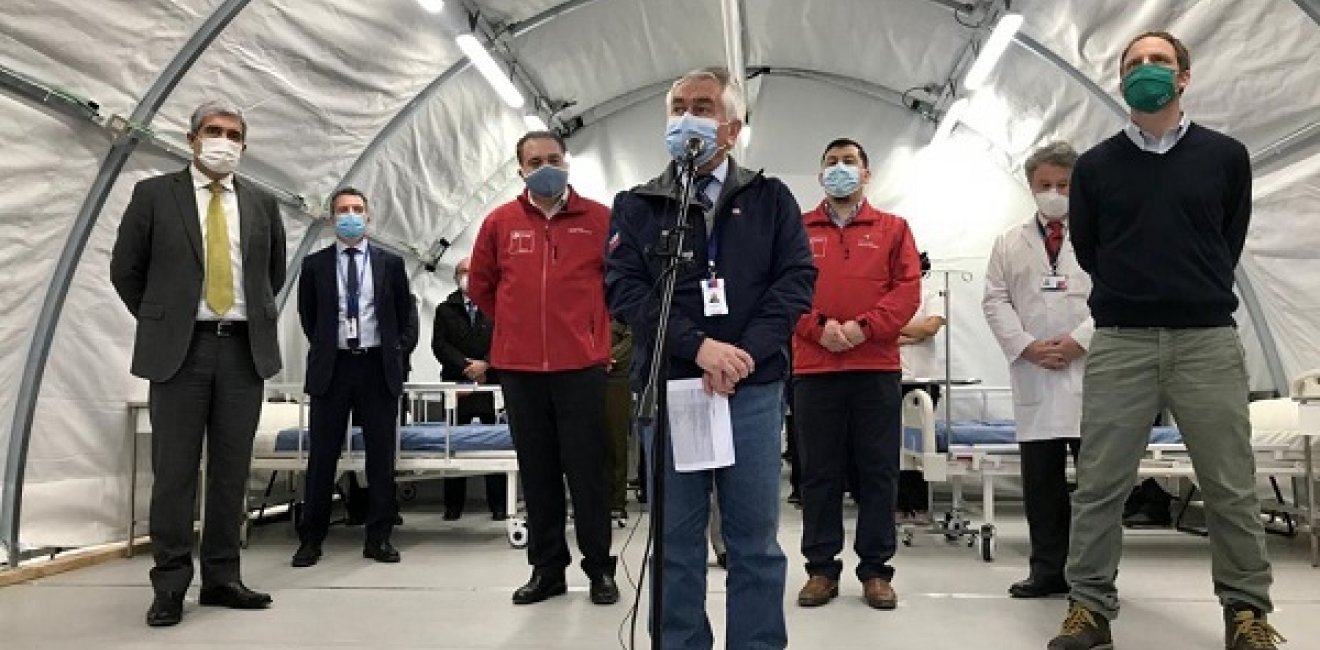

In June, amid a resurgence of coronavirus cases in Chile, Health Minister Jamie Manalich resigned while facing harsh criticism of his management of the pandemic, joining a growing roster of health authorities that have stepped down in Latin America in recent months.

The leadership change signaled a fall from grace for Chile’s public health authorities.

After Chile detected its first COVID-19 case on March 3, the government quickly imposed a quarantine in rural areas and an aggressive lockdown in cities. Testing and contact tracing appeared to pay dividends, as the number of cases remained low. By late April, the government was confident enough to begin loosening stay-at-home measures.

Chile had benefited from its high institutional capacity. It had the region’s highest rate of testing, and rolled out significant government stimulus to mitigate the pandemic’s economic fallout.

Then things fell apart. Cities shifted to a “dynamic quarantine,” maintaining lockdowns in neighborhoods most affected by the virus, while allowing others to resume business as usual. Soon, the number of cases skyrocketed. For a time, Chile had the third-largest outbreak in the region and the sixth largest in the world. It now has more than 370,000 cases and 10,000 deaths.

Original Sin

The resurgence in Chile revealed serious deficiencies in the Health Ministry’s understanding of the pandemic. Nowhere was this more evident than in the nation’s capital, Santiago, which accounted for almost 75 percent of cases in the second wave.

Initially, the government had focused on the affluent communities where globetrotting Chileans had brought the virus home. But the softening of Chile’s quarantine brought a rapid spread in the city’s densely populated low-income communities that Chilean authorities should have anticipated. After all, the city has long suffered from a stark economic divide, and many informal workers had no choice but to leave home to earn their daily wage, fueling the spread of the virus.

This phenomenon is not unique to Chile, of course. Informal neighborhoods in Argentina and Brazil have faced similar difficulties controlling the novel coronavirus. In Argentina, for example, nearly 1 million people live in these densely populated communities, where they rely on day labor and have little savings, food reserves or even easy access to basic sanitation. For Argentina’s health authorities, Health Minister Ginés González García said in an interview with the Wilson Center’s Latin American Program, the challenge is “unlike anywhere in Europe.”

Despite decades of healthy economic growth, Chile is one of the world’s most unequal countries, with wealth concentrated in a sliver of the population. The poverty rate in Santiago exceeds 15 percent. A reliance on informal work and privatizations have left basic services out of reach for many Chileans.

Public discontent exploded last October, after a small fare hike in Santiago’s public transportation system sparked unprecedented unrest. Millions took to the streets to demand education, health care and pension reform. To calm public anger, President Sebastián Piñera pledged structural changes, and promised a referendum on a potential constitutional rewrite. The pandemic froze the reform process, delayed the national plebiscite until October and largely marooned protestors in their homes. But the issues that led to last year’s uprising are unresolved, and the social peace is fragile.

Hiding in Plain Sight

Despite last year’s dramatic unrest, the former health minister said he was unaware of the extent of poverty and overcrowding in Santiago. Many Chileans saw his remarks as further evidence of the Piñera administration’s aloofness – a weakness that has deprived Mr. Piñera of the rally-around-the-flag approval bump many leaders in the region have enjoyed. Frustration with the president appeared to increase when he opposed legislation to allow Chileans to withdraw up to 10 percent of their pension savings. Lately, despite the virus’s continued spread, anti-government protests have resumed.

Out of the Frying Pan

By late July, Mr. Piñera was once again ready for a cautious reopening. By providing additional unemployment insurance and direct aid to informal workers, the government hopes this time around to staunch the economic bleeding without igniting another wave of the virus.

But even if the pandemic abates, the Piñera administration will have to turn quickly to its other crisis. The nation’s stubborn inequality, which long predates the current government, was unmasked and worsened by COVID-19, and now demands urgent attention.

Author

Latin America Program

The Wilson Center’s prestigious Latin America Program provides non-partisan expertise to a broad community of decision makers in the United States and Latin America on critical policy issues facing the Hemisphere. The Program provides insightful and actionable research for policymakers, private sector leaders, journalists, and public intellectuals in the United States and Latin America. To bridge the gap between scholarship and policy action, it fosters new inquiry, sponsors high-level public and private meetings among multiple stakeholders, and explores policy options to improve outcomes for citizens throughout the Americas. Drawing on the Wilson Center’s strength as the nation’s key non-partisan policy forum, the Program serves as a trusted source of analysis and a vital point of contact between the worlds of scholarship and action. Read more

Explore More in Weekly Asado

Browse Weekly Asado

Dengue Haunts South America’s Summers

Lessons from Costa Rica’s Economic Transformation

Women and Latin America’s Digital Revolution