A blog of the Middle East Women's Initiative

Greater attention and research must be paid to women in rural areas who continue to confront meaningful challenges with issues such as poverty, education, healthcare, and employment.

We cannot talk about women who live in the rural world without considering the colonial history, the policies put in place by postcolonial states, and the consequences of structural adjustment introduced during the 1980s. Due to the legacies of these structures, women who live in rural areas have not benefited from health, education, employment opportunities, and culture in the same way as residents in urban areas. In this context, we can ask whether they can be agents of change and overcome their handicaps to face new challenges, such as the absence of democracy, the aridity of the land, and climate change.

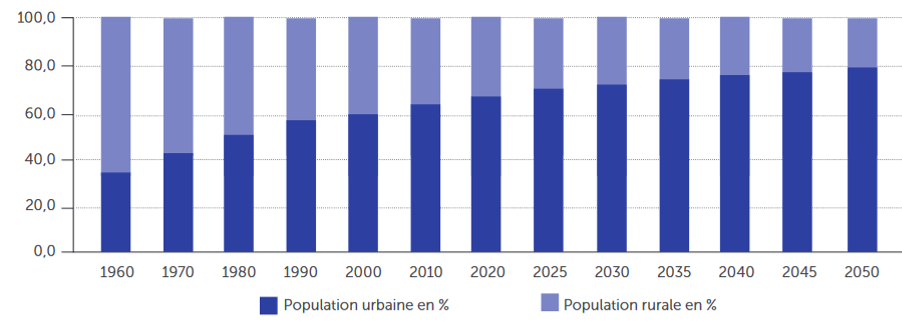

In Tunisia, women in rural areas are confronted with a myriad of challenges. In 2017, there were 1,786,261 rural women (INS, 2017), amounting to a third of all Tunisian women and half of the rural population. Beginning in the 1960s, many heads of households who could no longer provide for the primary needs of their families left to look for work in Tunisian cities, Libya, or France. Then came the departures of young men and some young girls who went to the cities from the 1980s on for family reunification, to pursue studies, or to seek better professional opportunities. Throughout this change, the roles and challenges that women in these areas have confronted have expanded over time. These roles and challenges address poverty, healthcare, education, and employment.

Poverty

The rates of poverty and extreme poverty declined between 2005 and 2015 in non-municipal regions, falling from 38.8% to 26% and from 15.1% to 6.6%, respectively. But, since the Covid-19 pandemic, poverty has worsened again. Eighty percent of women who live in rural areas are financially dependent on a male member of the family (INS, 2015). Only 1 in 5 rural women have their income compared to nearly 56% of men (MFFES, 2017). In these circumstances, women do not have a great margin of freedom in decisions concerning their destiny and/or that of their children.

Healthcare

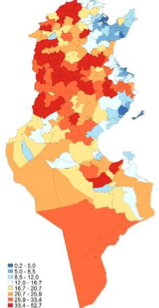

Access to healthcare is a challenge for women in rural areas and is inconsistent across different governorates. If they need to go to the nearest Primary Health center, women must travel an average of more than 4 km, sometimes on foot in the absence of means of transport. Women in rural areas also receive less healthcare consultation when pregnant than their urban counterparts (UNICEF, 2020). Furthermore, the attitudes of healthcare workers often go against women's rights regarding access to contraception, abortion (free since 1973), and screening for violence, among others. Budgetary restrictions in terms of training and recruitment impact caregivers and those in need of care in these areas. For example, during COVID-19, a young surgeon died in a faulty elevator in the hospital where he worked in Jendouba, a town in the northwest of the country. This incident, among others, provoked protests among young doctors who are increasingly leaving the country to work in Europe, Canada, or the Gulf countries.

Education

The education of children living in these rural regions also poses problems. Schools face serious infrastructure and maintenance issues, and students are often required to travel long distances on foot to get to school, with 27.9% of girls and 28.3% of boys traveling more than 3km to go to school, compared to 2.4% for children of both sexes in urban areas. The poor condition of buildings and the lack of teachers in these regions favor the interruption of classes, which impacts the results of national exams. When girls manage to escape all these difficulties, at the cost of many sacrifices, they are not sure, once they graduate, of finding a job.

Employment

In 2016 and 2017, unemployment among women with higher education degrees reached 41.5% and 39%, respectively, while the rate for men did not exceed 20.1% and 19%. Interregional disparities between women are often ignored despite being very large. Women in rural areas are particularly vulnerable to unemployment, even if they obtain university degrees. For example, Houda, who holds a master's degree, was found selling traditional "tabouna" bread on the roads of Kairouan to meet her needs; Mouna, 30, from the Mahdia region, an unemployed English language graduate, blew herself up in 2018 in front of the national theater and became another symbol of the "Arab Spring" revolution. There are also significant portions of the rural women populations that work in agriculture. These women typically do not own their land, spend a significant amount of their pay to travel to and from work daily, and are at risk of employment-related accidents because they do not receive compensation or protection.

Given the considerable changes in Tunisian society over the last several decades, greater attention and research must be paid to women in rural areas who continue to confront meaningful challenges with issues such as poverty, education, healthcare, and employment. Post-independence research has devoted little work to women who live in these areas. Greater emphasis on their experiences and needs will provide better and more human-centered data and create space for these women to continue to promote change in their respective regions.

Author

Visiting Research Professor, Middle East Institute, National University of Singapore; Former Minister for Women’s Affairs (January to December 2011), Government of Tunisia

Middle East Program

The Wilson Center’s Middle East Program serves as a crucial resource for the policymaking community and beyond, providing analyses and research that helps inform US foreign policymaking, stimulates public debate, and expands knowledge about issues in the wider Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Read more

Explore More in Enheduanna

Browse Enheduanna

Women are the Catalysts for Change in Lebanon

How Education Can Empower Young Women in MENA