A blog of the Brazil Institute

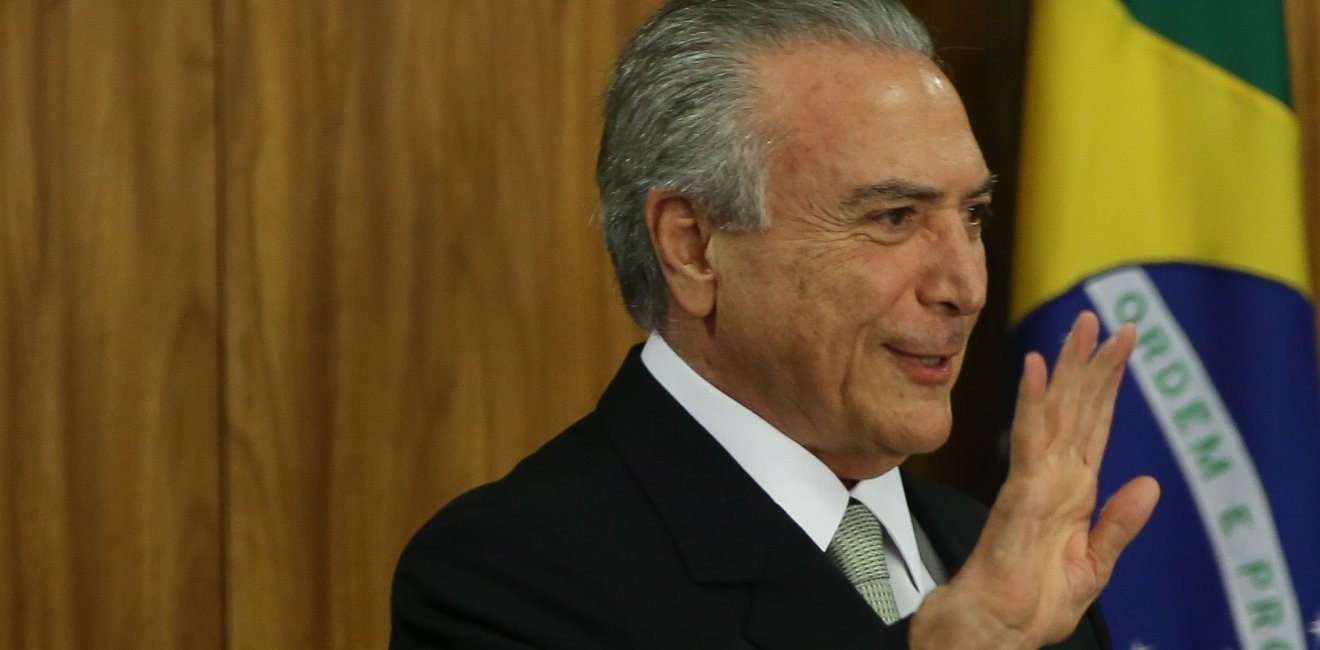

On Wednesday, May 17, the Brazilian newspaper O Globo made headlines for disclosing the existence of audio recordings that implicated Brazilian President Michel Temer in efforts to obstruct justice in ongoing corruption investigations. Their leaking has spurred serious conversations over graft charges and what some pundits consider inevitable: his ouster.

Though Temer denies wrongdoing and has categorically refused to resign, the situation in Brazil has escalated rapidly over the past weeks, leaving politicians, economists, and scholars shell-shocked. For now, it remains unclear whether he will be incriminated for allegedly encouraging hush money to keep former Speaker of the House and current inmate, Eduardo Cunha, silent. If Temer is found guilty in court (a sizable majority of the Brazilian population have already condemned him), he will likely be unable to navigate the turbulent waters of Congress and save his presidency from capsizing.

Yet, recent events are not the first time in Brazilian history to feature discussions of removing the head of state. Despite its historical proclivity for negotiated transitions, Brazil is well-versed in ousting its leaders, even in its earliest days. The country’s initial 1889 democratization uprooted centuries-old monarchic rule (first as a colony and then as an independent empire), and that first Republic dissolved when the 1930 Revolution ended the presidential pipeline of café-com-leite aristocrats (a Republic defined by its oligarchic, hand-picked selection of presidential successors from Brazil’s two most populous states, Minas Gerais and São Paulo). If Temer were removed, his name would join a long list of others now honored by Brazil’s street signs and universities.

In the past, these watershed moments of removing officials have frequently been accompanied by sweeping reforms, including new electoral processes, constitutional overhauls, and redistribution of the government’s checks and balances. Though it does not seem likely that there would be a constitutional overhaul should Temer be ousted, the Brazilian political system is experiencing burnout after decades of strain from within. The current crisis is its culmination, though one could also argue, or rather hope, that it will serve as a tipping point for action. Corruption allegations, clear electoral misconduct, and complex, institutionalized bribery schemes have arguably eroded the country’s bedrock of democratic governance. Exacerbated by the largest corruption scandal in contemporary history, the current crisis stresses the need for changes in the country’s political conduct and spotlights the vital role of the judiciary moving forward. With little restitution in sight, it is not far-fetched to say that people have lost trust in the system.

Nonetheless, significant confusion lingers around what would come next after potentially ousting both the original president, Dilma Rousseff, and her replacement, current President Temer.

Without question, this situation will set new precedents in the coming months, regardless of the outcome. Some are warily observing the country’s next steps, but Brazil has established procedures for the most unlikely scenarios, and this trend predates the country’s latest Republic. Even Brazil’s first president left office before finishing his term when he chose to resign in 1891 amid mounting pressures from an economic crisis known as the encilhamento, a purposeful shutdown of Congress, and naval revolts.

In a press conference on May 18, however, Temer announced he would not step down. In deciding to fight the accusations against him, he is following the most common path for Brazilian leaders faced with such antagonism. Most of their efforts, however, have failed to muster sufficient support to enable them to survive their terms.

The exact means of their various departures from the political scene differ widely. Some, such as João Goulart in 1964, left for exile following military coups. Others have resorted to leaving office preemptively—seeing that their forcible removal was imminent—such as Jânio Quadros, who chose to resign because of his “conscience.” One, the longest-serving president in Brazilian history, Getúlio Vargas, committed suicide after penning a lengthy farewell letter still immortalized today in history classes as the apex of Brazilian populism and as a testament to his unwavering desire for the population’s adoration.

There are also legal channels for removing a president, without his or her consent, which have been more in evidence since Brazil’s return to democracy in the mid-1980s. In the last thirty years, only three presidents have served out their full terms successfully. Of the other four presidents since Brazil’s return to democracy, two faced impeachment and two were initially vice presidents.

President Dilma Rousseff, under whom Michel Temer served as vice president, was impeached last August for manipulating the country’s current accounts, a crime of fiscal responsibility under Brazilian law. Rousseff denounced her opponents, decrying their attempts as a parliamentary coup, or golpe de estado, and continues to maintain they were motivated by political consideration rather than legal precedent. A majority in Congress disagreed, characterizing her decision to borrow from public banks to meet the target budget surplus as a campaign strategy in the build-up to the 2014 election. With a 61-20 majority, the Senate voted to remove Rousseff, and her Vice President Michel Temer was officially sworn in as the new president.

While Dilma Rousseff’s case is fresher in the people’s minds, the impeachment of President Fernando Collor de Mello is not yet ancient history. Collor was Brazil’s first directly elected president following the return to democracy. After Collor’s brother accused him of benefitting from a campaign financing scheme, however, investigations emerged from all corners of the legislative and judicial branches. In a televised appearance, Collor called for the people’s support and likened the impeachment to a coup attempt (a common tactic), but his rhetoric was ineffective. Instead, university students, donning black attire and face paint in the colors of the Brazilian flag, took to the streets in protests that augured those in 2013 and now.

Before the Senate could formally impeach him, Collor resigned in 1992, hoping this would terminate further investigations. Instead, the Senate persisted, voting to charge him with misconduct and barring him from running for office for eight years. Yet once these eight years were up, Collor reentered politics. He lost a race for the governorship of the Brazilian state of Alagoas in 2002, but later won senate races in 2006 and 2014.

Unlike in 1992 and 2016, the current president retains conditional support in Congress, making impeachment unlikely as long as the present (though tenuous) governing coalition holds with the Brazilian Social Democracy Party.

Initially, the judiciary branch appeared to be the avenue of his ouster, at least until a few days ago when the Superior Electoral Tribunal ruled to uphold the 2014 election results in a case regarding illegal campaign financing. Despite this temporary respite, Temer finds himself in a precarious position. Massively unpopular with the public and accused of corruption, he is on the defense. For many, Temer’s guilt is unquestionable and his declaration of innocence was unconvincing. Yet with no vice president, there are also significant questions over who would replace Temer and how that person will be chosen, as the next scheduled presidential election is still sixteen months away.

The fact that a second president could be forced from office so soon after Dilma Rousseff was impeached may seem extreme to foreign audiences. Yet Brazil’s history shows that political turmoil is often the norm. For decades, Brazilian leaders have seen their terms cut short, often under what appear to be unusual circumstances. However, this most recent crisis, even within this historical context, is unprecedented. Widespread corruption investigations and the media’s tireless coverage of politicians have awakened a nation-wide desire to rid the country of corruption, no matter how deep-seated it may be nor how detrimental the consequences are. The possible vacancy in short order of both the presidency and vice presidency provides even more untrodden territory for a country that has rarely followed a predictable path.

Author

Explore More in Brazil Builds

Browse Brazil Builds

They're Still Here: Brazil's unfinished reckoning with military impunity