A blog of the Kennan Institute

The removal of the last remaining Lenin statues in Finland in 2022 highlighted a change in how perceptions of Russia have shifted in Finland post-February 24, 2022.

A rethinking of Finland’s post–Cold War (1990–2021) relationship with Russia has grown in the past year, much as happened after the collapse of the Soviet Union some three decades earlier. Previously, the end of the Cold War was considered the end of Finlandization and Moscow trying to limit Finland’s sovereignty. Finland’s decision to seek NATO membership and the sea change in public sentiment and foreign policy toward Russia mark a definitive pivot in the relationship between these two geographic neighbors.

In September 2022, national surveys highlighted that 70 percent of Finns were in favor of ending visa issuances to Russian citizens. The head of the organization that conducted the survey interpreted the data by saying “the majority [of Finns] want to push back against Russia” and that Finns’ opinions have shifted to the same camp as the Baltic countries’ and Poles’ opinions. Finns’ previous reticence regarding America is also argued to be on the decline.

Understanding Finlandization

Finnish NATO membership was termed by the head of the National Coalition Party, Petteri Orpo, a final step in Finland joining the West. While this perspective is not uniformly accepted domestically, some researchers have endorsed it, saying that “the dust of Finlandization has been brushed off” and that Finnish NATO membership is the “culmination of Finland’s post–Cold War history.”

In international politics, “Finlandization” is considered a foreign policy strategy whereby a smaller state adapts certain domestic and foreign policies to the interest of a larger, often neighboring, country. In Finland, the term has emotional resonance and has influenced the debate on the country’s political culture, as well as over how Russia should be discussed in domestic politics. In this way, Finlandization became a keystone for debating the morality of Finland’s Cold War relationship with Russia.

Despite proclamations that Finlandization ended with the culmination of the Cold War, the debate simmered in the post–Cold War years, sharpening and gaining immediacy with Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea and subsequent full-scale invasion of Ukraine. In these moments, Finland’s relationship with Russia and Helsinki’s foreign policy decisions drew a more concentrated criticism. Finland’s post–Cold War relationship with Russia has increasingly been viewed in moral terms, according to which Helsinki was naïve in how it constructed its Russia policy.

Anna-Liisa Heusala, university lecturer at the Aleksanteri Institute, suggests that by renewed proclamations of an end to Finlandization, Finns are attempting to present “Finland’s place exclusively as a part of the West and with its back turned to the East. The label of Finlandization embodies dichotomous thinking.” In this discourse, “Finland was a ‘benevolent fool’ who immediately after [gaining] EU membership did not understand that joining NATO would be for the best.” Such sentiments became part of Finland’s post–February 24 state rhetoric about Russia. For example, Prime Minister Sanna Marin said that Finland and other European countries should have listened to the Baltic states’ warnings about Moscow for the past three decades.

Finland’s Pragmatism

Despite moralizing assessments of Finland’s Russia policy, Finnish decision-makers have been considered apt players of realist world politics. Mika Aaltola, director of the Finnish Institute for International Affairs, points out that Finnish foreign policymakers innovate “experimentally in order to find serendipitous perspectives in… emergencies and crisis.” Finland’s bid for NATO membership and its response to Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine can be considered one such emergency.

While Helsinki has worked over the past thirty years to become increasingly interoperable with NATO, the decision to apply for membership was nevertheless momentous. Former Finnish prime minister Alexander Stubb characterized Finns’ perspective on this matter as an example of the tension between idealism and realism toward Russia. For Stubb, attempts to retain a stable bilateral relationship after the Cold War were based on idealism, with realism now winning out and influencing Finland’s NATO bid.

President Sauli Niinistö echoed these sentiments in January 2023, saying that “Finland is an open and tolerant country... But being the most tolerant of all also has its pitfalls. Namely, evil is good at finding the one that is the most lenient.”

Finland’s newly proclaimed pragmatism toward Russia, however, has not found an equivalency in NATO politics. Finnish decision-makers and experts considered in early 2022 that acquiring NATO membership would be a quick and easy process. Turkey’s opposition was an unpleasant surprise, and the prolongation of the membership process into 2023 made Finnish decision-makers nervous, with some even questioning the veracity of NATO’s open door policy. As the British Ambassador to Finland noted, Finns are now learning that while NATO has an open-door policy, there are many other doors within the alliance.

Whether Helsinki will be joining a community formed around democratic values or simply a military alliance is also a subject of much discussion in Finland. While the former remains a sentimental goal in public opinion, realistic appraisals assess an uptick in the likelihood of the latter, owing to the unexpected obstacles that arose during the application process. The Finns acknowledge that the path to NATO membership has entailed a learning process and will continue to be so.

Finland’s International Role in Flux

A foundation of Finland’s relations with Russia for decades was the ability to maintain reciprocal trust, with an emphasis on Moscow’s faith that Finland was “not part of any secret conspiracy.” In the 1990s, the goodwill of Cold War relations lived on as what Russian deputy foreign minister Albert Chernyshev termed a similar “mental affinity” between the two nations that was not understood in the rest of Europe.

In August 2022, President Niinistö proclaimed that Putin's mask had come off: “The trust is gone, and there [is] nothing in sight on which to base a new beginning.” Helsinki will now need to find a new core principle for its relationship with Russia. Currently, this looks to be accepting NATO policy as Finland’s Russia policy.

Early signals can be seen, though more in terms of aligning the language of security objectives than of maintaining an autonomous policy. For example, rhetoric is slowly emerging in Helsinki that parallels the U.S. president Joe Biden’s interpretation of the world as a battle between democracies and autocracies. On his February tour of the United States, President Niinistö repackaged the domino theory, asserting to the press corps that “our membership in NATO is for democracy... If an autocratic system would win somewhere, it never stops. After one win, it might be another win.”

This is a marked shift from traditional Finnish rhetoric, heard as late as the fall of 2021, that attempted to promote dialogue as a form of de-escalating tension internationally. There is concern that Helsinki’s new policy direction, if handled improperly, could run counter to Finland’s long history of promoting itself as a peacekeeping superpower. Finns have marked experience offering good offices to conflicting parties and hosting numerous U.S.-Russia meetings in Helsinki.

Eyes on the Future

Finland’s changing relationship with Russia is part of a larger debate about where Finns imagine themselves and their allies, as well as what and how certain issues should be discussed in Finnish society. Matti Pesu and Tuomas Iso Markku of the Finnish Institute of International Affairs argue that Finland's Russia policy “is currently in profound flux.” Finnish society will feel Russia's second invasion of Ukraine for years to come, as will many other European societies.

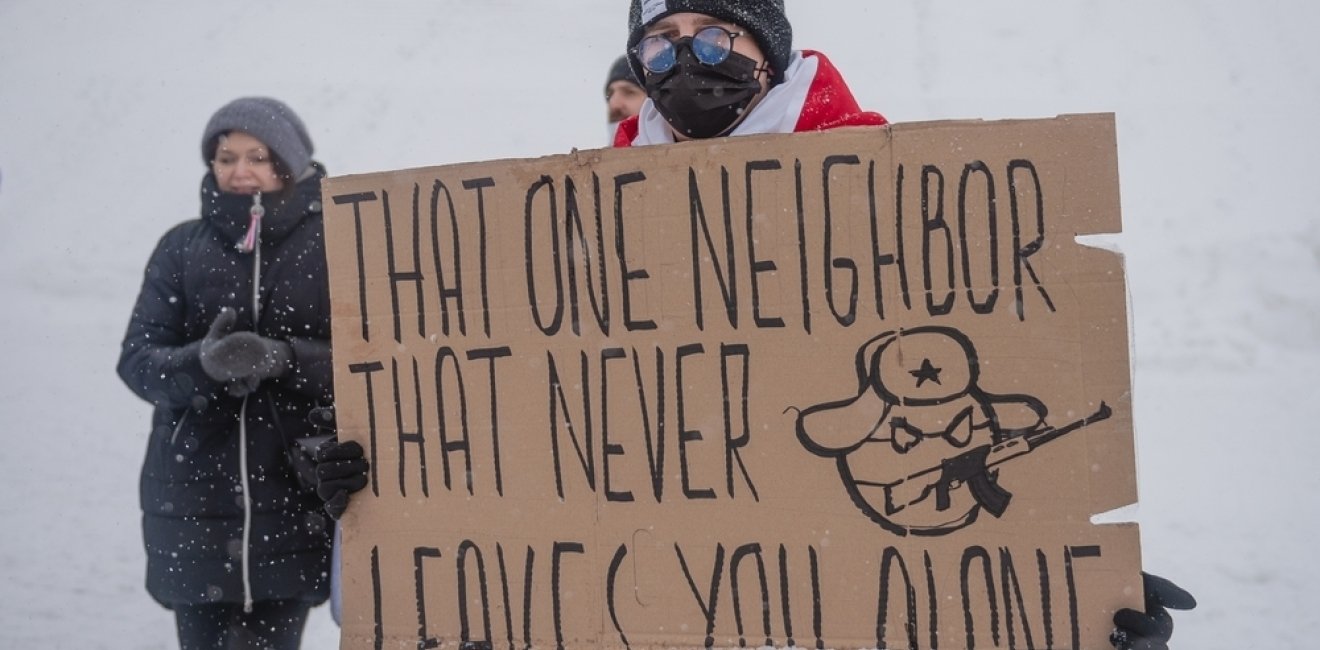

Kimmo Rentola, professor emeritus of political history at the University of Helsinki, argues that Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine has left a time stamp on Russia-Finland relations, likely marking the start of a new era. For Rentola, the events of the past year have already eroded societies and ways of thinking. While Finns’ trust in Russia may be gone, Russia will always be a geographic neighbor, and one that must be reckoned with. How Finns simultaneously shape their future NATO and Russia policies will influence the development of Finnish political culture and society for years to come.

The opinions expressed in this article are those solely of the author and do not reflect the views of the Kennan Institute.

Author

Doctoral Researcher, University of Helsinki

Kennan Institute

After more than 50 years as a vital part of the Wilson Center legacy, the Kennan Institute has become an independent think tank. You can find the current website for the Kennan Institute at kennaninstitute.org. Please look for future announcements about partnership activities between the Wilson Center and the Kennan Institute at Wilson Center Press Room. The Wilson Center is proud of its historic connection to the Kennan Institute and looks forward to supporting its activities as an independent center of knowledge. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Explore More in The Russia File

Browse The Russia File

Chechnya as a Model of Modern Russia

Russia’s Indigenous Communities and the War in Ukraine

Gas and Power in a Changing US–Russia Relationship