A blog of the Kennan Institute

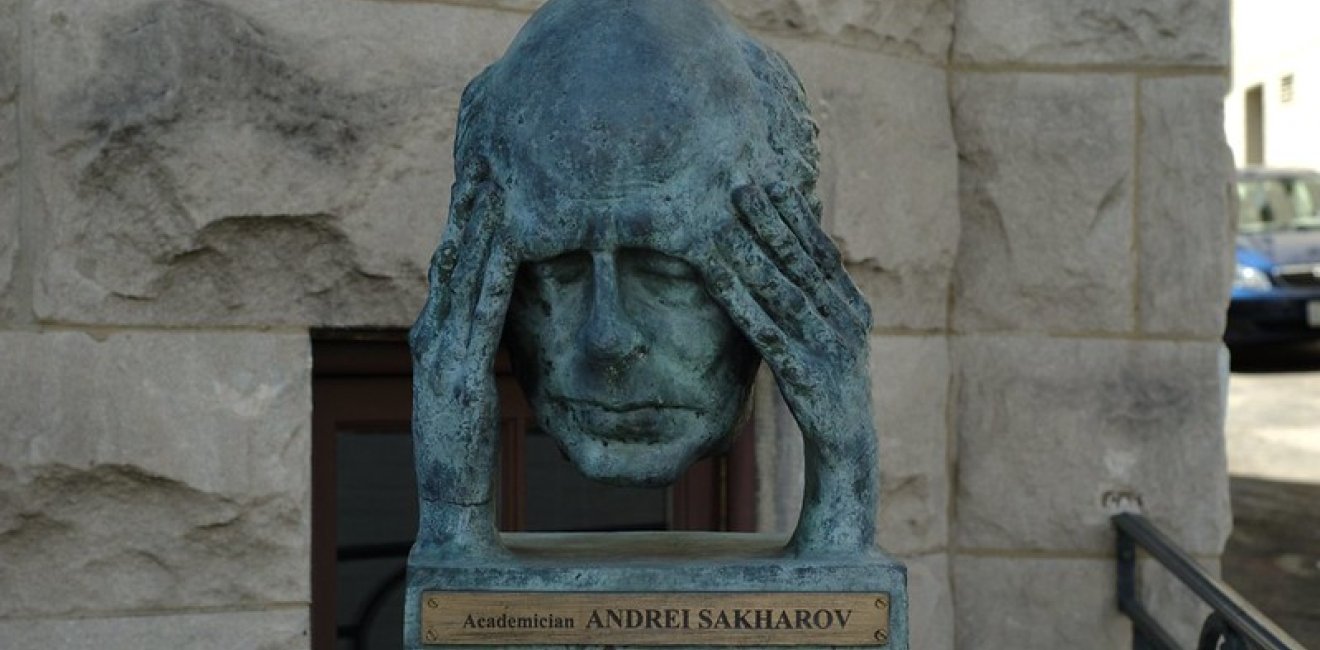

On December 28, 2021, the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation ordered the closure of the International Memorial Society, one of Russia’s oldest human rights and civic organizations. Memorial had been established in 1987 by a group of concerned citizens, including Nobel laureate Andrei Sakharov.

A year later the International Memorial Society was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, along with the Belarusian human rights activist Ales Bialiatski and the Center for Civil Liberties in Ukraine.

The real reason for the Russian state’s attack on Memorial was that the organization’s ongoing efforts to bring the crimes of the Soviet regime to light made it difficult for the state to celebrate the Soviet Union’s victory in World War II without also being held responsible for Stalin’s victims. The state prosecutor made the state’s aim of taking control over the portrayal of Soviet history explicit at the Supreme Court hearing when he accused Memorial of “incorrectly interpreting Soviet history” and creating a “false image of the Soviet Union as a terrorist state.”

Despite the official liquidation of the organization as a legal entity, Memorial’s members have continued their work on the memory project of coming to terms with the legacy of Soviet repression in the hope of building a democratic future. Unable to prevent this work, which is conducted throughout Russia’s regions, the Russian state has now come for Memorial’s champions.

Raid and Arrests

On the morning of March 21, 2023, in Moscow, Memorial’s leaders, staff, and their family members—including Ian Rachinsky, Aleksandra Polivanova and her mother, Nikita Petrov, Alena Kozlova, Galina Iordanskaya, Irina Ostrovskaya, Aleksandr Guryanov, and Oleg Orlov—had their homes and offices raided. Some, including Rachinsky, Orlov, Polivanova, and Guryanov, were detained and interrogated.

As the International Memorial Society has reported on social media and on its website, its files, computers, phones, flash drives, and other items bearing the Memorial logo, including a medical mask, were seized during the search. The reason for this renewed attack on Memorial’s leaders, whose ongoing work is an act of courageous resistance to Putin’s regime, was an allegation made by the organization Veterans of Russia that Memorial was responsible for rehabilitating Nazi collaborators whose names were included in their database of victims of Stalin’s mass repressions. The invasion of Ukraine, after all, has been justified in part by Putin’s false claims that Ukraine is an illegitimate state and needs to be de-Nazified.

In actuality, Veterans of Russia is concerned with only three of the more than three million names in Memorial’s database (inclusion of those three names in the database appears to have been an error, and one Memorial had previously corrected). There is no concrete information about what two of the three people were sentenced for.

The third was one of tens of thousands of ethnic Germans who began settling in Russia in the eighteenth century and whose descendants were persecuted during World War II. Although a minority of Soviet citizens collaborated with the Germans out of hatred for the Stalinist regime, many more, such as Gulag survivor Elena Markova, were sentenced to fifteen-plus years of hard labor in the Gulag or exile for simply having lived in areas under German occupation.

It is unknown what will happen to Memorial’s leaders in the wake of this attack.

The Politics of Memory

This action on the part of the courts and the state was meant to further intimidate any others from engaging in research that could question the state’s narrative of the past. It comes at a time when the Russian state is not only arresting protestors but prosecuting citizens of all ages who have dared to question the war online or even in the privacy of a personal conversation.

The civil society Russian citizens built in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union has been crushed by the state under President Vladimir Putin, who has silenced the last independent voices in the state-controlled press, clamped down on NGOs, and imprisoned anyone who criticizes Russia’s war on Ukraine. The state prevents those who wish to learn the truth about their past from doing so by restricting access to the archives to only those with repressed relatives, whom they intimidate with an opaque and byzantine bureaucracy despite their legal right to access their repressed relatives’ files in state archives.

Memory laws like those enacted in Western Europe to criminalize Holocaust denial and racism are used by the Russian state to label the regime’s critics “Nazis” and to criminalize interpretations of history that challenge the growing cult of victory in World War II. In fact, history in Putin’s Russia is being singularly distorted to justify the largest land invasion in Europe since World War II. Political repression is arguably the worst it has been in Russia since Stalin. The politics of memory have never had greater implications than they do today.

The opinions expressed in this article are those solely of the author and do not reflect the views of the Kennan Institute.

Author

Associate Professor and Arthur T. Fathauer Chair in History, University of Alaska, Fairbanks

Kennan Institute

After more than 50 years as a vital part of the Wilson Center legacy, the Kennan Institute has become an independent think tank. You can find the current website for the Kennan Institute at kennaninstitute.org. Please look for future announcements about partnership activities between the Wilson Center and the Kennan Institute at Wilson Center Press Room. The Wilson Center is proud of its historic connection to the Kennan Institute and looks forward to supporting its activities as an independent center of knowledge. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Explore More in The Russia File

Browse The Russia File

Chechnya as a Model of Modern Russia

Russia’s Indigenous Communities and the War in Ukraine

Gas and Power in a Changing US–Russia Relationship