A blog of the Latin America Program

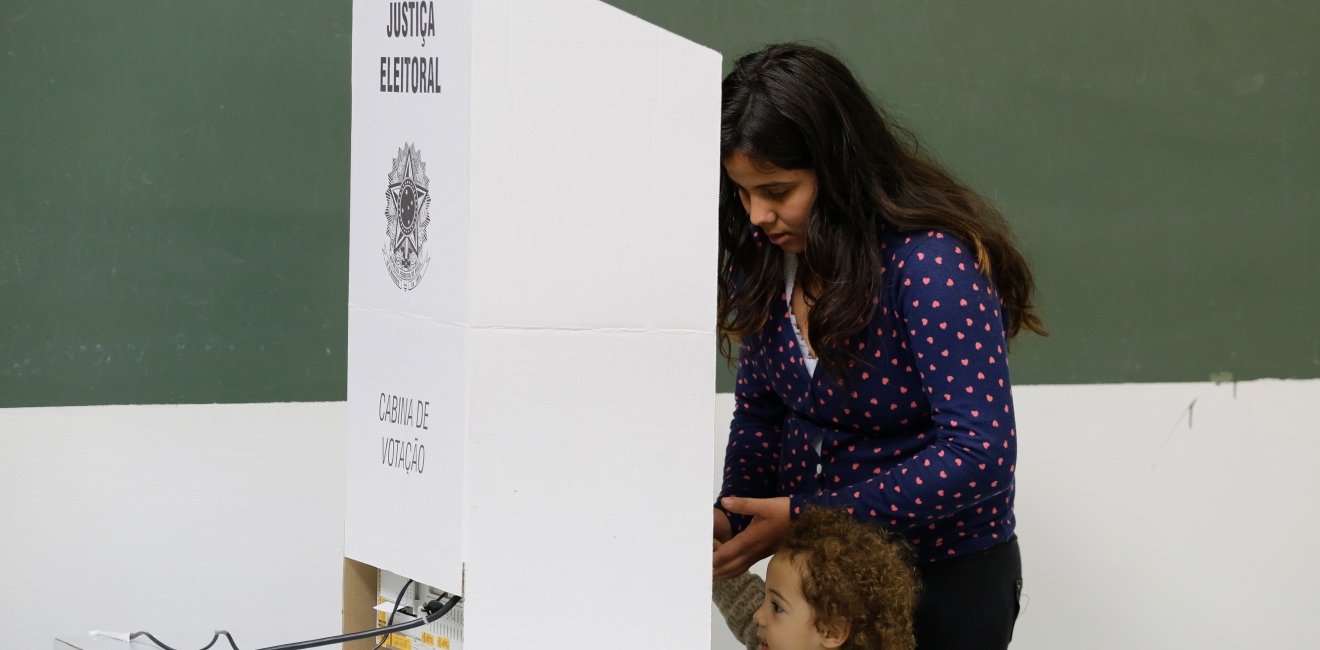

February 24 marked the 90th anniversary of women’s suffrage in Brazil. That achievement was the result of sustained efforts by Brazilian women’s movements. But as Brazilians gear up for elections in October, it is remarkable how little progress has been made in women’s political participation nearly a century after Brazilian women won the right to vote.

Despite accounting for 52 percent of the population, women represent only 15 percent of legislators and 11 percent of ministers in Brazil. Dilma Rousseff was the only female president in the country’s history. Brazil ranked 108 out of 155 countries in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap 2021 Political Empowerment subindex, which assesses the presence of women across parliament, ministries and heads of state. Although the number of women in parliament has nearly doubled in the last two decades, Brazil has actually seen its ranking fall by 22 spots since 2006 for women’s representation at the highest level in political and public office.

While Brazilian women were among the first to win the right to vote in Latin America, their relative political empowerment lags much of the region.”

While Brazilian women were among the first to win the right to vote in Latin America, their relative political empowerment lags much of the region. For example, Costa Rica, where women’s suffrage was achieved in 1945, has closed 55 percent of the political empowerment gap.

Greater female representation in politics does not only matter to women; research shows it has broad economic and social implications. Gender equality in political participation is linked to greater economic stability and participation, heightened democratic outcomes and increased peace and prosperity. In Brazil, increased representation of women at the local level has also been shown to reduce gender-based violence.

Gender equality in political participation is linked to greater economic stability and participation, heightened democratic outcomes and increased peace and prosperity.”

Today, the case for prioritizing this agenda is even more critical, given the disproportionate impacts on women of the COVID-19 crisis. Yet at the current rate of progress, it would take Brazil over 145 years to achieve gender parity in political empowerment.

Gender parity in politics often reflects broader female empowerment. Brazil is no exception. Women’s political prospects are undermined by gender-based economic, social, institutional and cultural barriers.

Violence against women in politics is a particularly pervasive barrier to political participation. In Brazil, 81 percent of sitting congresswomen and 75 percent of women running for mayor in 2020 experienced political violence. Worse still, that might be an undercount, as fear of retaliation and tolerance of this behavior hinder reporting and the adoption of policy responses.

It would take Brazil over 145 years to achieve gender parity in political empowerment.”

Laws also condition women’s political participation, including those related to economic empowerment. While Brazil has made progress in this area, women still have only 85 percent of the economic rights afforded to men, and lag behind in economic participation and opportunity. Laws mandating equal pay for work of equal value and prohibiting gender-based discrimination in access to credit, for example, could improve women’s economic empowerment and opportunities.

Electoral laws and rules also constrain women’s political prospects. While gender quotas and parity laws drive female representation in politics, the characteristics of quota systems and electoral funding mechanisms shape the overall outcomes. In 1995, Brazil established a 20 percent quota for female candidates in local elections and expanded it, in 1997, to 30 percent for elections at any level. It adopted additional improvements in 2009 and 2016, including a requirement that parties allocate at least 30 percent of campaign spending to promote women’s candidacies. In 2021, the parliament passed legislation to combat political violence against women.

Violence against women in politics is a particularly pervasive barrier to political participation.”

Notwithstanding these developments, Brazil remains far from achieving political equality due to underlying gender norms and discrimination, a broad lack of support for women’s engagement in political life, and inadequate enforcement of the regulations just mentioned. In terms of next steps moving forward, more forceful monitoring and punishment of campaign funding violations and incidences of political violence, enhanced measures to ensure favorable placement of female candidates on party lists, and approval of pending legislation to ensure female representation in party leadership and establish reserved seats for women, could serve to more effectively increase female representation in Brazilian politics.

Author

Senior Legal and Gender Specialist, World Bank

Latin America Program

The Wilson Center’s prestigious Latin America Program provides non-partisan expertise to a broad community of decision makers in the United States and Latin America on critical policy issues facing the Hemisphere. The Program provides insightful and actionable research for policymakers, private sector leaders, journalists, and public intellectuals in the United States and Latin America. To bridge the gap between scholarship and policy action, it fosters new inquiry, sponsors high-level public and private meetings among multiple stakeholders, and explores policy options to improve outcomes for citizens throughout the Americas. Drawing on the Wilson Center’s strength as the nation’s key non-partisan policy forum, the Program serves as a trusted source of analysis and a vital point of contact between the worlds of scholarship and action. Read more

Brazil Institute

The Brazil Institute—the only country-specific policy institution focused on Brazil in Washington—aims to deepen understanding of Brazil’s complex landscape and strengthen relations between Brazilian and US institutions across all sectors. Read more

Explore More in Weekly Asado

Browse Weekly Asado

Dengue Haunts South America’s Summers

Lessons from Costa Rica’s Economic Transformation

Women and Latin America’s Digital Revolution