Marina Ovsyannikova: “Putin’s Propaganda Factory Will Soon Crumble”

The below is a Kennan Institute Long Read.

A blog of the Kennan Institute

The below is a Kennan Institute Long Read.

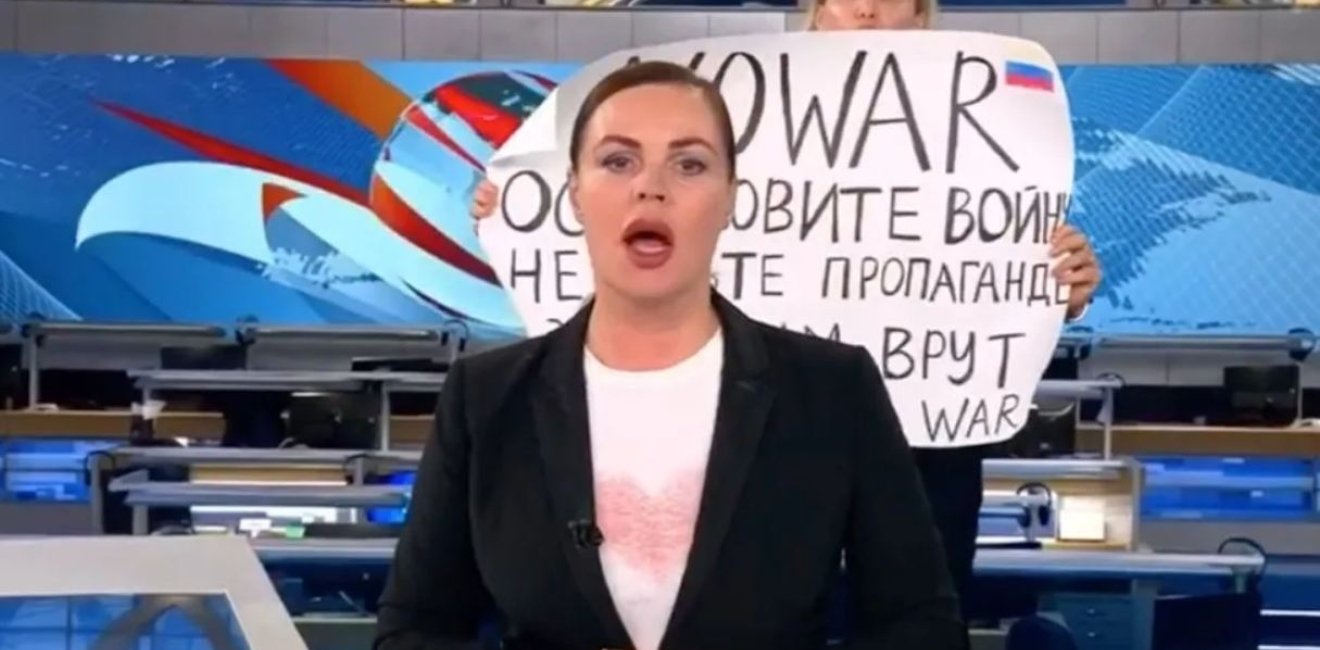

Marina Ovsyannikova, formerly the editor of Russia’s state-owned Channel One news program “Vremya,” made international headlines last year on March 14, 2022, when she burst into a live broadcast to appear behind news anchor, Ekaterina Andreeva, holding a poster condemning the invasion of Ukraine and the propaganda perpetrated by her own employer. The consequences followed immediately: she was fired, denounced by her co-workers, and accused of working for British intelligence. She was charged with an administrative offense for participating in an “unsanctioned rally.” She was fined for “discrediting” the Russian army. Her parental rights were restricted, and she was put under house arrest, where she remained until she fled the country.

You are currently in Berlin. What are you doing here? How do you spend your days?

Until recently I was writing a book. I have now finished it. The book has been translated into several languages, and its first release was in Germany. That’s why I am here. I am promoting the book.

What is the book about?

It’s my autobiography told through the prism of last year’s events. It’s also the story of how and into what Channel One had been turning over the years, when I worked there. The story of how a perfectly [normal] news channel had been transforming into a Kremlin propaganda mouthpiece.

Did you write the book under house arrest?

Yes, I started writing under house arrest. When we escaped, I continued to write in France. For almost three months, I stayed away from the public eye. I was waiting for political asylum and writing the book.

Why were you put under house arrest?

I was fined several times for anti-war statements. This was followed by a criminal charge for my protest near the Kremlevskaya embankment, when I named the precise number of children killed [during the war] in Ukraine. Back then, 352 children were listed on the UN website; now this figure is unfortunately much higher already. This was the reason for opening a criminal case [against me]. Several [court] sessions took place. At first, they determined whether to remand me and decided on house arrest.

What’s life like under house arrest?

I was locked within four walls. They did not allow me to go outside. A perimeter was established along the walls of my house, and I could not even go into my backyard. House arrest looks different for different people: some are allowed to go grocery shopping. I was locked within four walls. My son left home and maintains zero contact with me. My [former] husband took my daughter away from me. My mom said that I ought to be put in jail; she is a Putin supporter. So there was no one to help me. Fortunately, a young woman came [to my rescue]; she was taking care of my social media and offered help. She flew from Samara to Moscow when she found out that I was under house arrest. She brought me food. Neighbors shied away from me, everyone did. The guards isolated me completely, they did not even let cars with food deliveries in.

How long were you under house arrest?

I spent two months [under house arrest] and decided to escape. My lawyer, Dima Zakhvatov, said that I ought to flee, that this was my only chance, because the next stage would be real jail. We frantically thought about how to arrange my escape.

How did you arrange it?

It was Dima Zakhvatov who arranged it. Reporters Without Borders helped. Until the last moment, I did not believe that it would work out, because it was a reckless scheme—escaping with a child, without documents….

You literally cut off your ankle monitor and went into the night, like they do in the movies?

Yes, just like in the movies, it was a [true] Hollywood thriller. Dima Zakhvatov kept telling me to flee as soon as possible. But I couldn’t flee, because they took my daughter away. I realized that I would never flee without my daughter. I’d rather go to jail than flee without her, because [otherwise] I would not be able to see her for years. I was under house arrest at home; she was under house arrest at my former husband’s apartment, locked up. It was a whole big drama.

How did the drama end?

My daughter managed to escape from my former husband. She escaped to me. Social services came, but they could not take her away, because there was no court ruling on removing the child from her mother’s custody. My daughter was expelled from school; she couldn’t even go to school. This was simply hell. In the end, Dima Zakhvatov found out via which country we could escape. We literally swapped seven cars along the way, the last one got stuck in the mud, we ran out into an empty field in search of a road. There was a person escorting us. It was pitch dark. There was no mobile connection. We literally had to follow the stars!

You don’t have a sense that they simply allowed you to escape? There was no surveillance, there was no police chasing you….

No, I don’t feel that way. Everything had simply been well organized. We chose Friday night, when police take a break. We had two days to get beyond Russia’s borders. I was put on the federal wanted list on Monday only. [My] case officer came to the office and put me on the federal wanted list.

But you removed the ankle monitor on Friday. They do get an alarm right away.

They do get the alarm. But what do they do? They call your home, check on what happened. Sometimes no one picks up, so no big deal. In the end, police never came to check. No one chased us with siren lights. We left Moscow quickly, and that’s it.

What do you mean, “that’s it”? You mean that there is a way to leave the country without documents?

Of course. No one cancelled the option of illegally crossing the border. That’s what my daughter and I did. I just can’t tell you where exactly we did it.

Is it a common practice?

Yes, of course. The women from Pussy Riot crossed the border that way. Masha Alyokhina did the same thing: she cut off her ankle monitor and ran.

This all works when someone knows about you on the other side of the border and waits for you, right?

Yes, someone waited for us and met us [on the other side]. Everything went well, everything was well prepared.

What happened once you found yourself outside Russia? Did you ask for political asylum right away?

We thought for some time about where it would be best for us to apply for political asylum. We did it in France.

Macron offered you this option right away, correct? Back in March of last year.

Yes, he offered it the day after [my] protest. I was still being interrogated, and Macron had already offered me political asylum and diplomatic protection. I did use this [opportunity] eventually, when I needed help for real, because until the last moment I didn’t want to emigrate. But everything became such a tangle in the end that I faced a choice between emigration and prison.

Has your case been reviewed? You got the asylum?

Not yet; my case is under consideration. This is not such a fast process. Right now, I am in the European Union on completely legal grounds, because I have a German work visa.

Did you resolve the conflict with your ex-husband?

He placed a restriction on my parental rights. There was a court hearing, which ruled that our children ought to live with their father, because their mother is involved in political activity. I have absolutely no doubt that this ruling was dictated from above. The problem is that my husband has cut off communication with me. He’s been avoiding contact with me, my lawyers, and my friends since March 14, since the day I broke into the live broadcast. Before that, we got along fine. We were divorced, but we kept in touch, talked about our kids’ future and various daily issues. But the kids lived with me on a permanent basis and sometimes went to his place. After my protest he immediately—the very next day—blocked the possibility for the kids to leave the country. He acted against me in an underhanded way. For crying out loud, he even tried to prevent me from selling the car. I managed to sell the car exactly two days before the court ruled to have it seized. This is crazy! Meanwhile, I got so scared of getting arrested right after the protest that I gifted the house to our children. I have absolutely nothing left, I am homeless. My former husband has now erased his daughter from his life too. He doesn’t even interact with her.

Is he still working for Russia Today?

Yes.

Is he an ideologically-driven person? Does he believe this war is necessary?

He has always read [Alexander] Dugin, he had [books by] Dugin on his bookshelves. That’s what he believes in.

Let’s go back to your story and talk about what brought you to this point. We know that you were born in Odesa in the late ‘70s. How and why did you end up in Russia?

My father was from Western Ukraine, and my mother is Russian. They met in Odesa. Five months after I was born, there was an accident, and my father died. Mother left the city. She had no choice, because her husband was dead. She went back to her parents in the Urals. I have lived my entire life in Russia. I consider myself Russian.

Why did you become interested in journalism?

I had a tough childhood. My mom and I found ourselves in Chechnya. She was invited to work in Grozny, and I started school in Grozny. We lived there up until the time when the first Chechen war started. Our apartment was destroyed. We fled to the Krasnodar region. My mom went to work for a local radio station. I [often] went with her to the office and got interested in journalism. Sometime around my 9th grade I decided that I would be a journalist. I got into the Kuban University and worked as a news anchor at the GTRK Kuban television channel.

And how did you find yourself at Channel One in Moscow?

There was a change of management at the Krasnodar station. I was told that I would not be a news anchor anymore. I submitted a letter of resignation on the same day. I went to Moscow, and in Moscow I started everything from scratch. I worked for a newspaper and for a sports channel. And then it so happened that I was introduced to the managing editor of a news program on Channel One. He helped me get a job. I became a writer on Channel One.

This was in 2003, correct?

Yes, in 2003. I was assigned to [news anchor] Zhanna Agalakova’s team.

What do writers do?

They write lead-ins for the news. A writer writes [it], and an anchor reads it out loud.

2003, Channel One, you are working as a writer, you are working exclusively with information, with the news. Back then, did the Channel One news programs fit your worldview, your political beliefs, the way you understand and sense the world? You didn’t find this work revolting?

In 2003, there was no propaganda factory [yet], and Channel One was still perfectly information-driven. Degradation happened gradually. Degeneration began from around 2007, possibly from Putin’s Munich speech.

Fine, but in 2007 you continued to work for Channel One against your own will?

At that point, my first child was born, then my second. My focus shifted to family. By then I was not making a career at Channel One. My husband was making a career. I took care of the home and kids and was just working on a schedule that was convenient for me. I understood clearly what was going on, I understood clearly the political situation, I simply buried my head in the sand. [But] over the last few years, it became unbearable. Like anyone else, I have a ton of personal issues. I just hid behind my family and lived in my own cozy little world. We got ourselves a home, comfortable income. I tried to sit it out, I knew that I wouldn’t be able to find another job under the current circumstances, because, as you yourself know, over the last 20 years Putin has destroyed all independent media in Russia, so television journalists have to either leave their profession altogether or quietly do their jobs.

Was the management team that handled news programs, where you worked, a tight-knit group?

Of course not. It was always a snake pit. Snitching and denunciations always flourished there and were encouraged by the top management. This is one of the reasons why it was better to mask and hide any discontent. I felt like an outsider on that team. I didn’t get too close to anyone. All my friends were from outside my work.

And closer to 2022, what were you doing at Channel One?

I was working on international affairs, on video exchanges.

You received videos from international news agencies, right?

Yes, I monitored international news and followed the international agenda. There was a different reality in front of me, a different image on my screens. I understood really well what was going on in the world, because I watched CNN, Sky News, Reuters, etc.

You got the source information from Western news agencies and adapted it for the Russian audience of Channel One?

Yes, [I adapted them] to the Russian reality. From the vast amount of news, we fished out the information that worked against Ukraine and the West. That was the only thing we did over the last years.

This was literally your only agenda?

Yes, this was our intentional agenda. If something came up on the TASS news feed, something pro-Russian spoken by some politicians in Europe, then we immediately had to comb through the internet and find that speech.

Do you feel ashamed, as a professional and as a human being, for having participated in this constant manipulation?

Yes, Roman.

So why didn’t you quit sooner?

Here is how I justified it to myself: I was working off screen, I wasn’t responsible for it because my face and name weren’t on it. I was just a small cog in this machine. And I thought that maybe I’d sit there a bit longer. I had been looking for other possibilities for a while, but, as you know, there weren’t that many options.

Did the management of news programs at Channel One know that there was going to be a war? Were you being prepped for something unusual?

No, there was no preparation. No one knew. It was a shock for everyone.

Even for your boss, [Kirill] Kleymenov?

I think that yes, for Kleymenov it was also a shock, because everyone’s faces were just…well, I don’t even know how to describe them. Such confusion and such shock! I had never seen such horror on the faces of my co-workers.

Were you working on February 24?

No, I was not working on that day. It was my week off. We work in weekly shifts, but I remember it all really well….

You’re lucky to not have been working.

I turned on my phone and got a flood of these alerts from different media…

Did you also get a flood of messages from your co-workers? “We’re f*cked, we don’t know how to work now! We don’t know what to do, how to live!”

No. No one internally discussed the editorial policy. Everyone [always] strictly follows the clearly defined rules.

Even in such critical situations? This is an extraordinary situation, even by Channel One standards.

You know, it was a shock for everyone, and everyone was stunned and silent, as if shell-shocked.

So you went back to work, your work week began. Did any of your co-workers refuse to produce [news] pieces or write lead-ins about the war? Did anyone try to sabotage [the workflow] or simply step aside? Did anyone do anything at all?

I know that one person didn’t show up at work, simply didn’t show up, that’s it. Others kept working as if hypnotized, kept doing what was required of them.

Did you have special staff meetings [about the war]? Did [the management] try to reassure you or suggest quitting? Was there any separate, special conversation with the staff?

No, and I write about it in my book. There was one staff meeting, where our boss showed up and said: sit tight, you’ve got a cushy job. In a war situation, the Kremlin will only be supporting the security agencies, the army, and the propagandists, so don’t fret.

You’re well protected, you’re in safe hands.

Yes, yes, yes, and everyone understood it all [very well].

Everyone understood it all, apart from you, apparently. Tell me how you pulled off your protest on live television.

I came to Ostankino at 2 p.m....

Before that, you wrote what you wrote on the poster.

Yes, on Sunday, ahead [of my protest], I made a poster at home and recorded a video message. I sneaked the poster into work in the sleeve of my jacket. And I was already getting ready to burst into the live broadcast when the managing editor called and told me that we need to redo [Vasily] Nebenzya’s soundbite. We had to clip off a different segment. I ran off to the editing room, we redid something. And I see that the Vremya program is already coming to an end, I’m not making it! I burst [into my office], grabbed the poster, and bolted behind Katya Andreeva’s back.

What were you thinking in that moment?

That if I they catch me before I get to the studio and stop me from bursting into the live broadcast, they will simply leave me to rot in the [FSB] basement on Lubyanka [Square], and no one will ever know about it. This was my greatest fear.

So only publicity could save you once you took this step.

Yes, that’s why it was crucial that I carry my protest to the end.

Everything happened behind Ekaterina Andreeva’s back. Did anyone convey her reaction to you? Did she damn you? We all know that this anchor’s image will forever be like this, with a poster behind her back that describes what she does.

She has commented [on the situation] on social media.

No more than that?

No more than that.

After your protest on Channel One’s live broadcast, which I view as heroic, you gained a lot of fans, but at least as many haters. Haters argued that nothing stopped you from being part of the propaganda machine for decades. And it is actually a fair point. What prevented you from ending this work for the propaganda machine sooner? Just the convenient schedule?

I would have ended it sooner…but I already told you what I thought: I wasn’t responsible because my face wasn’t on any of it, I worked off camera, and no one knew me—that’s number one. Second, I understood perfectly well that I had nowhere to go under the current circumstances, when all television was under state control. Third, I had loads of personal problems: I had two dependent children whom I had to feed, a difficult divorce, an unfinished house, and loans. I am an ordinary, weak person.

With this protest, you raised the bar so high that no one, of course, thinks of you as an ordinary, weak person now. You are the only person from the television industry who did what you did, so naturally people expect an entirely different level of responsibility from you! The last time you and I chatted was six months ago. You said back then that you found yourself in a difficult situation, because propagandists labelled you a traitor and independent journalists did not accept you because of your background. So you are sort of an outsider everywhere. Has the situation changed, now that you’ve been under house arrest and spent time with an ankle monitor?

Not really. There is almost no support from journalists. There is almost no support from Ukrainians. Still just hate.

Does it hurt?

I’ve experienced so much pain lately that I’ve already learned not to react [to it]. Here’s what I think: a few more years, and I will be left one on one with myself. It’s more important to me what my own conscience will say [then] than what oppositional journalists or people working for Putin will say.

After your protest with a poster, your boss Kirill Kleymenov just about called you a British intelligence operative live on air, correct?

Yes.

Why did he do it? Was he trying to save his own ass? Did the [Russian] security services force him?

It’s his favorite thing to talk about—British spies. He loves it. Especially after the Skripals were poisoned [in the British city of Salisbury]. So there is nothing surprising here. The rhetoric about traitors and British spies is his favorite propaganda trick. I wasn’t even particularly surprised. My son though got a very good laugh [out of it]. He said that if I were a spy, I’d be the worst spy of our time.

Did you forgive Kleymenov?

I understand that he is a hostage of the system, he does what he is told. One wrong move and he is dead.

Can you say the same about [Konstantin] Ernst? Do you feel the same about him?

Yes. Putin is trying to smear everyone in this mud as much as possible, to make them all his accomplices. They will be with him till the end.

Do you keep in touch with any of your former co-workers?

Only with Zhanna Agalakova. Among former co-workers, Zhanna is the only who supports me; the others are keeping silent, staying low.

You support lustration. Do the state propaganda employees deserve to be put on trial?

[Margarita] Simonyan deserves trial, [Vladimir] Solovyev and [Olga] Skabeeva deserve trial—the top propagandists. But regular employees…I don’t think they deserve lustration. Video editors, camera crew members, text editors…I am not so sure [about them].

When Simonyan and Solovyev are put on trial, they will also say that they were hostages of the system, that they had nowhere to go and had no options….

If they had rebelled in the beginning of the war and put on Swan Lake on Channel One, maybe things would have gone differently.

Marina, do you realize that you too may find yourself on trial, if the judges in the “beautiful Russia of the future” find your protest on Channel One unconvincing? It’s not impossible.

Look, these are different things. Everyone must be punished to the extent of their guilt, depending on what they were doing during the war.

Do you feel that you are also responsible for what Russian television has become?

Of course I am. I feel guilty, I am trying to atone for this guilt, I am not silent, I use every chance I get to tell about how propaganda works, I support Ukrainians, I gave my Václav Havel [Human Rights] Prize to a volunteer organization that evacuates refugees from Ukraine. I am helping several Ukrainian families financially. I am doing everything to atone for my guilt, and I am ready to go to Ukraine to help with reconstruction after the war ends.

Let’s just tick off everything you’ve lost over the year since your protest.

I lost everything. I lost my home, I lost part of my family, I lost my homeland, my peaceful life. Thirty years on, I became a refugee for the second time in my life. War has destroyed my life for the second time. The first time was when Russian troops obliterated my house in Grozny, and this time the Kremlin took absolutely everything away from me.

And what have you gained, thanks to your protest?

I’ve gained support in Europe, I’ve gained good people.

Knowing the consequences of this protest in your life, would you have done it again?

Yes, I would. Because at that moment someone had to say that the emperor had no clothes. [Putin] has built a propaganda factory and this entire cardboard stage set around him, which will crumble very soon. I am like that boy from [Hans Christian] Andersen’s fairy tale who had to say it out loud. Everyone knew, but everyone is silent.

So now you’re in Berlin, there’s certainly no going back to Russia for you under the current regime...

Right, I’m facing 10 years [in prison]…

I apologize for what may be a dumb question, but it seems appropriate here: what are your creative plans?

I want to defend freedom of speech in Russia, I want to help journalists who are political prisoners, I want to work with Reporters Without Borders. I am in touch with the Women’s Forum in Berlin; we want to protect women’s rights and primarily help Ukrainian women affected by the war.

You want to be a human rights defender?

Yes.

How do you make a living now?

Over the past few months, I lived off the money from the sale of my car. Now [that] my book is out, I’ll get a small [honorarium] to live off of.

Where are you going to live?

In France. France will become my home.

Do you believe that you will go home [to Russia one day]?

I would very much like to go home, because my mom and my son are there. They are brainwashed by propaganda. I don’t know how soon I will be able to see them. I’m afraid that my mom might die, God forbid, and I won’t be able to go to her funeral, that I will never be able to hug her again. This is all very complicated. This is all very difficult.

This interview originally appeared in Russian on Иными словами, a Kennan Institute blog. It has been edited lightly for style and clarity.

The opinions expressed in this article are those solely of the author and do not reflect the views of the Kennan Institute.

After more than 50 years as a vital part of the Wilson Center legacy, the Kennan Institute has become an independent think tank. You can find the current website for the Kennan Institute at kennaninstitute.org. Please look for future announcements about partnership activities between the Wilson Center and the Kennan Institute at Wilson Center Press Room. The Kennan Institute is the premier US center for advanced research on Eurasia and the oldest and largest regional program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more