A blog of the Brazil Institute

The global economic slowdown caused by the coronavirus crisis is changing the profile of Brazilian exports. And it continues to increase Brazil's dependence on its undisputed top trading partner, China. Data from Brazil’s Special Foreign Trade Secretariat shows a 7 percent drop in overall exports during the first half of 2020, which is in line with the expected economic contraction for the economy this year. According to the latest Focus Report—a Central Bank-led weekly survey with market analysts—the median forecast for the Brazilian economy is a 5.28-percent contraction by the end of 2020.

Exports to China over the first six months of the year amounted to USD 34 billion—slightly higher than 2019 (and twice what was sold over the same period in 2015). On the flip side, however, sales to the United States and Mercosur countries dropped 32 and 29 percent, respectively, compared to 2019.

China has topped the list of Brazil’s trading partners since 2009 and gobbled up 33.7 percent of Brazilian exports in the first half of 2020.

The impact of the coronavirus on imports was smaller, at just 5.21 percent. But these numbers show a more equal split among Brazil's three main partners: China, the European Union, and the United States.

Commodities Continue to Carry Brazilian Exports

The COVID-19 pandemic has hit some sectors harder than others. With regard to Brazil's foreign trade, industry has clearly slipped out of favor. The numbers of countries or regions where Brazil usually sells manufactured goods has also decreased, in general terms. However, the impact on total exported volume has been softened by the continued strength of Brazilian commodities.

José Augusto de Castro, chairman of Brazil Foreign Trade Association (AEB), believes the pandemic emphasized the chronic problems of competing in manufactured goods markets and the resilience of commodities. “In commodities, Brazil has productivity. Whatever the price or exchange rate, Brazil will be competitive. With favorable demand and exchange rates, as we have now, Brazil sells at ease, with no worries,” states Mr. Castro.

For instance, the five main goods exported to China are commodities. For these five products, exports have increased by 13.4 percent.

In the opposite direction, Brazil's far-more diversified export portfolio to the United States was affected significantly. Aircraft, for instance, saw sales fall 75 percent. Across the board, shipments to the United States declined 32 percent in the first half of 2020.

“Trade with the U.S. is a mix. It used to be much more based on manufactured goods, but this is decreasing mainly because of oil. Brazil had a trade surplus with the U.S. Today, however, it has a strong deficit. The U.S. market demands prices Brazil is unable to offer,” says Mr. Castro.

A similar process occurred in Mercosur. This trade relationship with regional South American partners is essential to Brazil, as it allows the country a chance at selling value-added goods—unlike in its trade relations with China. On a local level, the auto industry plays a huge role in Brazil-Mercosur relations.

However, since last year, Brazil has seen declining sales to Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay. This began with the economic crisis in Argentina and has worsened due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This year, China surpassed Brazil as Argentina’s top trading partner as well.

“Brazil has a chronic problem. Cost is an issue that mainly affects manufactured goods. There was already a dependency on China, which has increased. The market for manufactured products in Brazil, South America, and Argentina is in crisis. Brazil has nowhere to export manufactured goods,” Mr. Castro tells The Brazilian Report.

Brazil in the Trade War

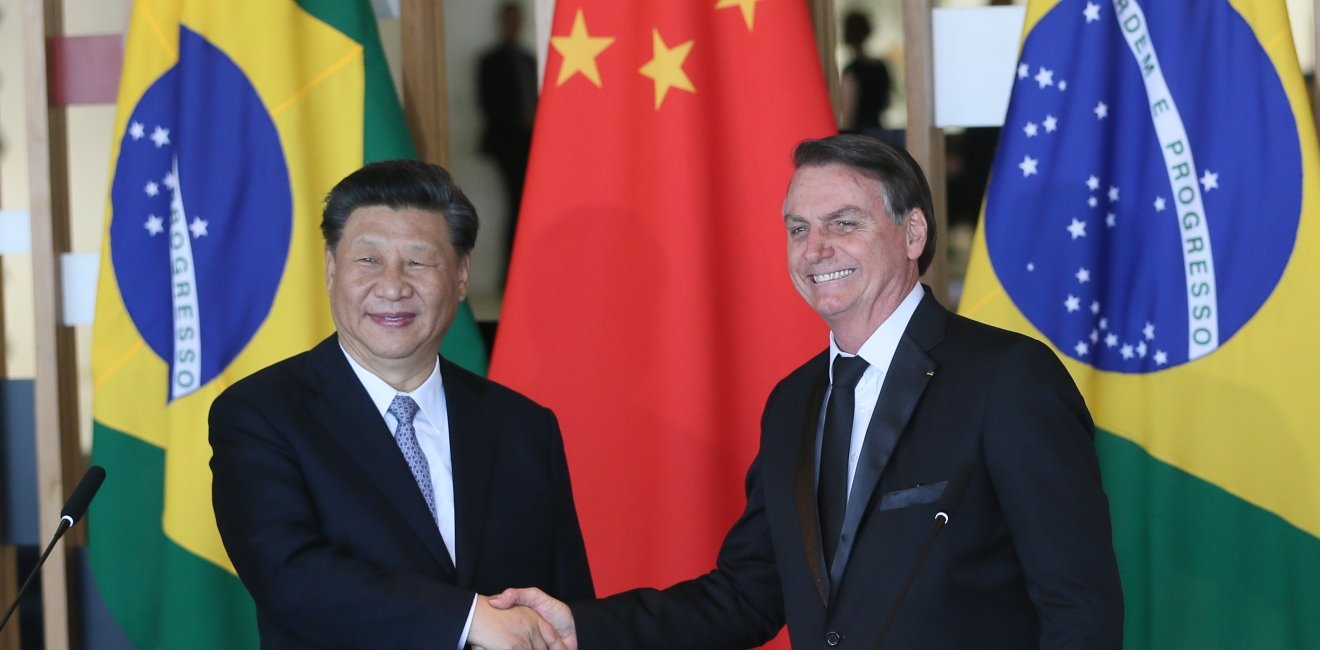

Although increasingly dependent on China, the Brazilian government under President Jair Bolsonaro has adopted a pro-U.S. stance. Among Bolsonaro’s supporters and close allies, anti-China sentiment is common. One recent example of this sentiment in action was when Brazil signaled its support for a U.S. proposal at the World Trade Organization that was essentially a broadside at Beijing.

And in a live online broadcast on July 30, the president deliberately avoided mentioning the word “China” when discussing vaccines. “We took part in Oxford’s consortium, and it seems that [the vaccine] will work, and 100 million units will arrive for us. It is not from that other country, no. Okay, guys?”

This anti-China stance—following the cues of U.S. President Donald Trump—has led to several warnings from the Chinese embassy to Brazilian authorities. In March, one of the president’s sons, Congressman Eduardo Bolsonaro, tweeted that “China is to blame” for the COVID-19 pandemic. The official representative of China in Brazil responded, demanding a retraction: “His words are extremely irresponsible and sound familiar. They are an imitation of his dear friends. Upon returning from Miami [where the Bolsonaro delegation met with Mr. Trump], he, unfortunately, contracted a mental virus, which is infecting the friendship among our peoples.”

There is also what seems to be an unwillingness among Brazilian authorities to accept the involvement of Chinese company Huawei in Brazil's future 5G operations. However, pushing the firm out will be easier said than done, as Huawei currently operates in Brazil and supplies 80 percent of all operational radio antennas in the country.

“The U.S. invites Brazil to take a stand against China, the primary market today. The world tries to be equidistant; Brazil takes sides. You need to start evaluating the business aspects, not of today but the future. The pandemic showed that Brazil depends on commodities; they have no option,” says Mr. Castro.

Like the content? Subscribe to the Brazilian Report using the discount code BI-TBR20 to get 20 percent off any annual plan.

Author

Brazil Institute

The Brazil Institute—the only country-specific policy institution focused on Brazil in Washington—aims to deepen understanding of Brazil’s complex landscape and strengthen relations between Brazilian and US institutions across all sectors. Read more

Explore More in Brazil Builds

Browse Brazil Builds

They're Still Here: Brazil's unfinished reckoning with military impunity