A blog of the Kennan Institute

BY GRIGORII GOLOSOV

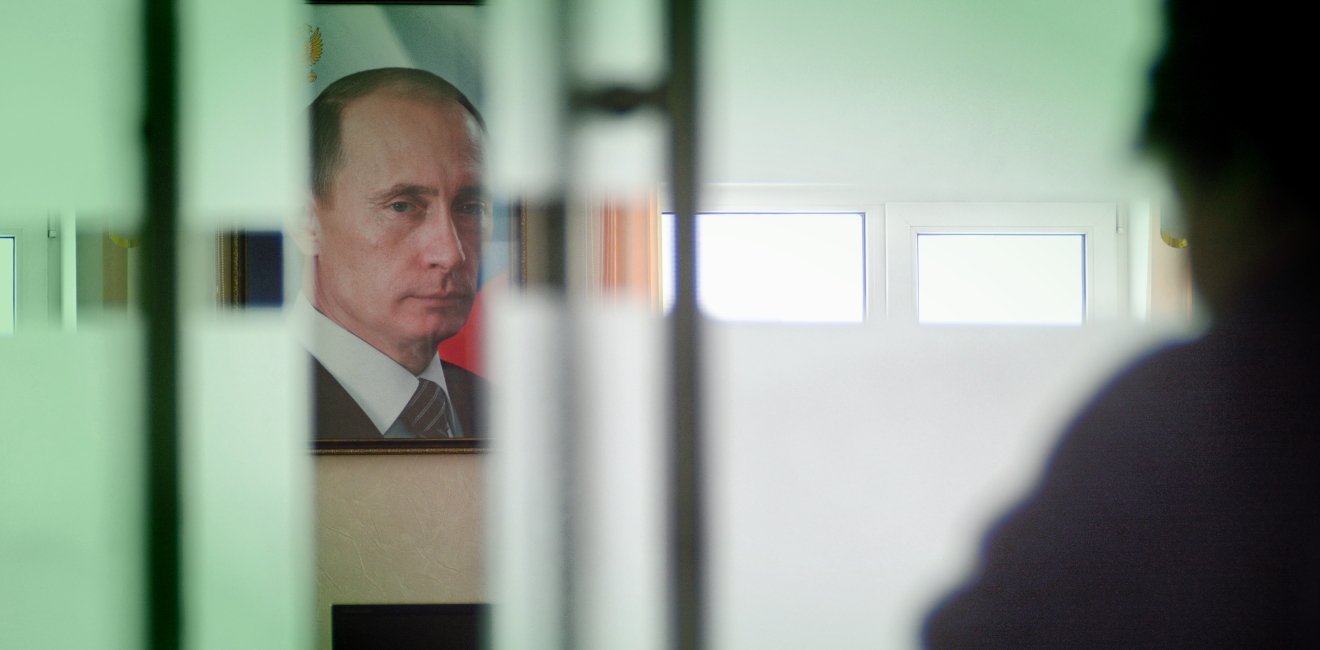

It is the Russian president Vladimir Putin who in my opinion poses the main threat to the Russian political regime’s long-term survival. But before going into this, I will clear up a few questions about Putin’s main opponent, Alexei Navalny, who has established himself as the leader of the Russian opposition. Last year Navalny survived an assassination attempt, underwent medical treatment in Germany, and, in mid-January, returned to Russia. He was detained at Moscow’s Sheremetyevo airport and Tuesday was sentenced to effectively 2.5 years in prison.

Before Navalny’s attempted poisoning, his democratic credentials and his integrity in dealing with the Russian authorities had been subject to doubt and caused concern even among opposition circles. Some of the antidemocratic claims deserve only a cursory mention because of their invalidity. Chief among them is Navalny's so-called nationalism, something he has been repeatedly accused of. Indeed, in 2007–2008 Navalny did participate in an effort to expand the opposition’s political base through a coalition with civil nationalism. Given the circumstances of the time it was to my mind the right tactical move. Russia’s liberal opposition may even return to the issue later, but for now it has lost all relevance. Russia’s authorities have prevented civil nationalism from developing and have installed their pocket political figures, such as the writer Zakhar Prilepin, to pose as “nationalists.”

Second, some see Navalny as a potential autocrat. Because this claim has no basis in actual fact I will only note briefly that critics expressing this view hate the very idea of Russia’s opposition having a leader. There have always been ample critics of the opposition who have invariably served as props of authoritarian political orders. From a functional point of view, however, leadership is but a coordination mechanism—no more, but no less.

The third charge that often comes up is that “Navalny is the Kremlin’s agent.” There is even less factual basis for that than for the two previously mentioned ones. It would take extraordinary intellectual rigidity to continue saying that after all that has happened in recent months. He did not die from poisoning, those conspiracy theorists say, therefore he was the Kremlin’s agent. This is ridiculous.

Any moves by Navalny that could theoretically be identified as directed by the Kremlin were hard to identify. But supporters of the Kremlin agent theory do not need facts to stay convinced. Their argumentation is based on unsubstantiated assumptions that Navalny in some cases acted in agreement with the implicit wishes of the Russian leadership. He may have even contacted real Kremlin officials to get to a better mutual understanding. I will now say something that might sound blasphemous to many. If those claims were true, they would not tarnish Navalny. Real politics—that is, the struggle for political power, not just mobilization for protest—is a complex game. Those who play it have to interact or even cooperate despite all divisions because the prize can only go to one of them. They do this for tactical purposes, often without informing their supporters. This is normal.

Of course, this does not happen in all political regimes. In a democracy, cooperation between the government and the opposition is so routine it is seen as a sign of a functioning system. On the other hand, many dictatorships have zero tolerance for opposition and use repression against all kinds of dissent. Halfway between these two extremes are various “soft” autocracies, including the kind that Russia belongs to, electoral authoritarianism.

Electoral Authoritarianism

Electoral authoritarianism is a system that emulates democracy while being an autocracy. Opposition parties are tolerated and elections are held regularly, but they never lead to a real change of government. An actual change of government might occur in such regimes but for other reasons, not because of an electoral loss. Autocratic incumbents often resort to electoral falsification and vote rigging to stay in power, but those kinds of means are dangerous because elections have to appear “real” to the population, at least to significant parts of it. Otherwise the delicate balance is lost and the population starts to suspect foul play.

Clearing the political playing field of the most inconvenient opponents and establishing a monopoly on information are more efficient ways of clinging to power. For an autocrat, the real victory is not when he retains power as the result of an election, which is assumed by default, but when he can claim victory with some credibility, when he can say, “I won in a fair contest, I have my people’s support, there is no alternative.” The Belarusian president Aleksandr Lukashenko was not successful in credibly claiming electoral victory last year and a massive popular protest ensued.

Electoral authoritarianism has become a global phenomenon relatively recently, but political science has already accumulated a sufficient body of data to say with certainty: authoritarian regimes’ survival directly depends on such credibility. A recent study led by the Swedish political scientist Staffan Lindberg has found as much. Those electoral authoritarian regimes that can count on a long life were able to “institutionalize electoral uncertainty,” that is, to appear to “win” elections as a result of real competition, Lindberg and his colleagues showed. As Lindbergh and his colleagues statistically demonstrated, those authoritarian regimes that enjoy a longer existence are able to meet those conditions during the first three electoral cycles.

Russia’s political regime seemed to have succeeded at that. If we consider the 2003–2004 electoral cycle as Putin’s first, he has already cleared four of them and is on the verge of getting through the fifth.

Surkov’s Design

Russia’s political system has not emerged out of nowhere. It is a product of design, and one of its chief designers was Vladislav Surkov, a political operator who served in various roles in the presidential administration and the Russian government between 1999 and 2018. He was the ideologue and the architect of a system that has a “national leader” at its top, a carefully groomed “party of power,” a select and well-paid “systemic opposition,” and an utterly marginalized “nonsystemic opposition” that is the real opposition. I will venture here a second blasphemous thought: Surkov did show a strategic vision and political intuition. He knew what he was doing.

What Russia’s ruling politicians were left to do was to use Surkov’s smart design to their advantage. They could have been successful. Would it have been good for Russia? I think not. Living without authoritarianism is better than living with it. From Egypt to Mexico, resilient electoral authoritarian regimes have brought stagnation and misery to most of the countries where they were established. However, the ruling circles of these countries had no reason to complain. They enjoyed the good life, because if there is one distinctive feature those kinds of regimes share, it is widespread corruption. The story of “Putin's palace,” as well as thousands of similar stories of corruption on a lesser scale, indicates that this is exactly what happened in Russia. The exorbitant oil prices of the 2000s helped a lot, but Surkov’s legacy cannot be overestimated. He did create a functioning authoritarian system for the Russian elites to benefit from.

Naming the Glitch in the System

But they have botched it. At some point the system crashed, and its systemic problems grow. That glitch has a name. And the name is Putin, not Navalny. Having played by the rules for the last time in 2008, when Putin handed over power, however insincerely, to Dmitry Medvedev, Putin subsequently put his personal safety above the goal of survival of the system. Because of this Putin has made Russia’s security apparatus the main pillar of his power structure and a key component of the Russian ruling class. Usually, authoritarian leaders avoid this, correctly understanding that excessive reliance on siloviki makes them hostage to their all-powerful guards. Why submit to someone who completely depends on you, if you can keep power to yourself? Putin’s personal biography may be the reason why he has chosen that path.

Let me emphasize: Putin has made his personal security the state’s priority over that of the system. Had Putin remained prime minister in 2012 instead of returning as president, his chances of holding on to de facto power would have been very high. In 2024 he would have been able to remain in power as the head of Russia’s State Council or some other institution. For the authoritarian leader, moves of that kind bring with them a certain degree of uncertainty. There are no absolute guarantees in such situations. However, it is precisely this, the institutionalization of electoral uncertainty, that scared Putin so much that he sent all of Surkov's meticulous designs down the drain.

Now that Russian politics has deviated from the subtle dynamics of electoral authoritarianism, it is becoming more confrontational and repressive. The person who has emerged as the leader of the Russian opposition is so unacceptable to the authorities that attempted murder seemed a logical solution.

As the massive January protests in defense of Navalny showed, the only communication strategy available to the regime is to intimidate and arrest its opponents. This only testifies to the fact that Russian electoral authoritarianism’s chances for long-term survival are dwindling. It is not Navalny or even the US State Department that is to blame for this [as the Kremlin likes to say] but Vladimir Putin: a person is a systemic failure.

This piece first appeared in Proekt and has been translated with permission.

The opinions expressed in this article are those solely of the authors and do not reflect the views of the Kennan Institute.

Author

Professor and Head of the Political Science Department, European University at St Petersburg

Kennan Institute

The Kennan Institute is the premier US center for advanced research on Eurasia and the oldest and largest regional program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Explore More in The Russia File

Browse The Russia File

Chechnya as a Model of Modern Russia

Russia’s Indigenous Communities and the War in Ukraine

Gas and Power in a Changing US–Russia Relationship