A blog of the Kennan Institute

BY MIKHAIL FISHMAN

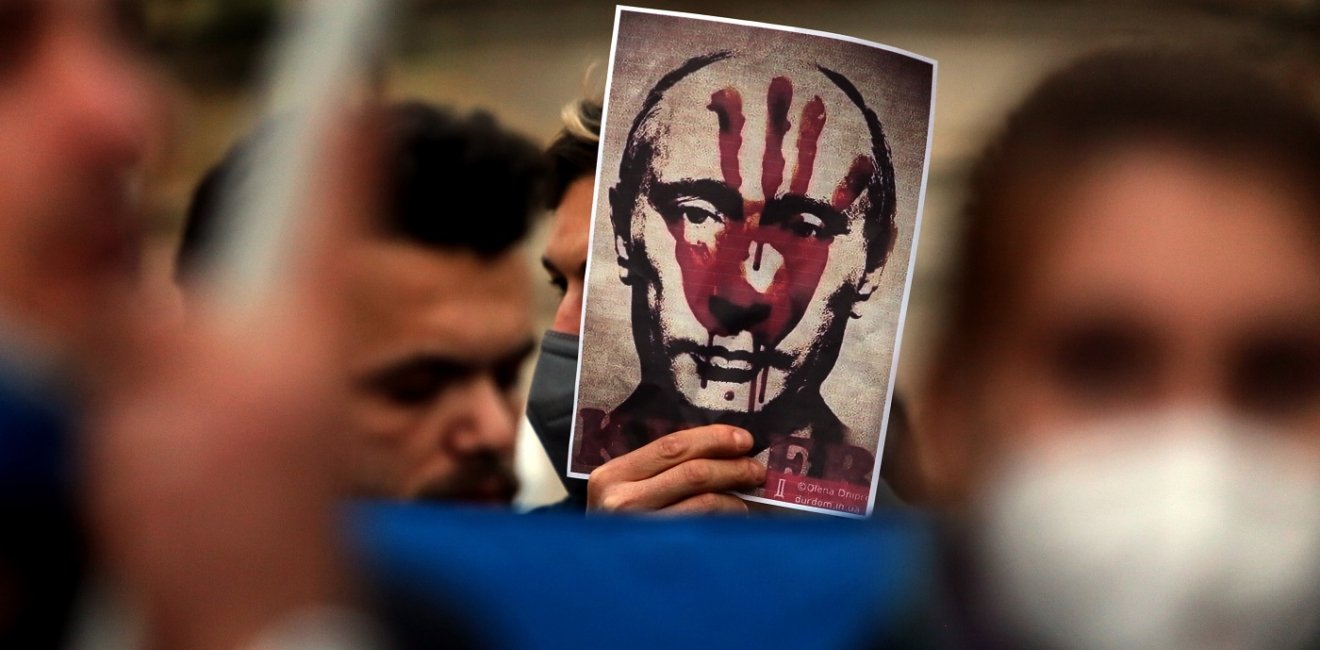

Disregard for human life and dignity has been a hallmark of Vladimir Putin’s devastating war in Ukraine, marked by violence not seen in Europe since the Yugoslavian wars of the early ’90s. The Ukrainian government is investigating more than 11,000 suspected incidents of war crimes and says the Russian military intentionally targets schools, museums, and other civilian infrastructure. Western leaders accuse Putin not only of unlawfully attacking a sovereign country but of attempting to fully erase Ukrainian identity and culture. Scholars and experts across the world debate whether Putin’s Russia qualifies as a fascist state or whether it is closer to a far left Stalin-type totalitarianism.

Some similarities are obvious on both accounts. As the Ukrainian philosopher Volodymyr Yermolenko has put it, Putin’s views on Ukraine look like inverted Nazism: “Jews were for Nazis ‘the Other’ which wanted to ‘be like you.’ Ukrainians are for Russians ‘like us’ which now want to be ‘the Other.’ And therefore have to be exterminated as major enemy par excellence (‘anti-Russia’).” And the Russian propaganda effort to label all Ukrainians Nazis follows the pattern of Stalin’s concept of the intensification of the class struggle while approaching socialism: the more the Russian military is stuck in its fight in Ukraine, the more Ukrainians are branded as a “Nazified population” as a whole, as opposed to the initial phase of the war, when Russian propaganda depicted Ukraine as a pro-Russian nation oppressed by a Nazi government.

Apparently, no single historical analogy can fully describe Putin’s invasion, but it is obviously based on totalitarian ideas. The goal of Putin’s war is to “get Ukrainians back home,” that is, make them the same as Russians (or Belarusians, controlled by Putin’s vassal Lukashenko). Translated from Russia’s propaganda language, the denazification of Ukraine means desocialization, the deformation of its social structure: as a nation, Ukrainians must be turned into a formless entity that would serve the interests of the state (as the Soviet people did under Stalin) along with Ukrainians’ maternal Russian people. Technically, this effort could be described as a far right fascist type of action inside the Stalinist logic of the relationship between the state and the nation.

Military experts and human rights watchers tend to see in the war crimes of the Russian military in Ukraine a repetition of the same criminal actions that the Russian military committed in both wars in Chechnya starting in 1995: destroying cities, slaughtering civilians, practicing torture, rape, and humiliation. They suggest the same reasoning: insofar as Russia’s military seems to commit similar crimes in every conflict, Russia’s military culture and organization are to blame.

Yet Russia’s brutality in Ukraine seems not to be limited to long-term issues inside Russia’s military. It’s not just a military but a political assault—and much more than that. Russia’s war crimes in Ukraine, though committed on an unprecedented scale, are of a piece with how the Russian state treats its own citizens.

It is not only the invading looters and murderers in Ukraine that enjoy impunity for their criminal actions: so do representatives of probably every law enforcement arm of Russia’s government inside Russia. Riot police beat protesters, the FSB has a mandate to kill enemies of the state, penal correction officers torture inmates, and so on. It is a system based on indifference and dehumanization that Putin attempts to spread over Ukraine—the same strictures he has been promoting inside Russia from his very first day in power.

At the beginning of his rule, Putin could have had no notion of what policies he would pursue or what future for Russia he might aspire to, but his dehumanizing approach was already shaping his agenda when he undertook his first military invasion in the fall of 1999. In 1995, the First Chechen War was bloody and brutal warfare. But it was Putin’s Chechen war of 1999–2003 that was transformed into a punitive operation on a political level when every disloyal resident of Chechnya was labeled a terrorist, just as, twenty-two years later, Ukrainians would be presented as “a Nazified population.”

Putin’s war in Chechnya unfolded under the slogan “No mercy, no negotiation.” In October 2002, authorities did not make a single effort to rescue hostages held in the Dubrovka Theater during the Nord-Ost siege in Moscow before launching an assault on terrorists, a striking difference from the Budyennovsk Hospital hostage crisis in June 1995 and sending a clear message: human lives mean nothing when weighed against Putin’s main mission, to avoid the humiliation of Russia.

The same approach dominated two years later when more than 300 hostages, most of them children, were killed in a military assault on armed terrorists during the Beslan school siege in the North Caucasus. “Some would like to tear from us a ‘juicy piece of pie.’ Others help them”: this was Putin’s response to one of the most tragic and ruthless rescue operations the world has ever known. Human lives again meant nothing. Compounding this moral failure, the catastrophe of Beslan was shamelessly used as a pretext to cancel gubernatorial elections in Russia and to further harden Putin’s authoritarian grip.

Overall, the story of how Putin’s Russia turned into an ideologically Stalinist dictatorship, wherein an individual is reduced to a cog in the machine, is multidimensional and complex. It can be explained in historical terms: throughout its history, Russia has rarely—almost never—enjoyed freedom and respect for human life.

Social factors certainly played a role in the growing authoritarianism: Putin emerged as a leader in the context of growing nostalgia, overwhelming frustration, and ressentiment, aggravated by the Russian Central Bank’s default of 1998. A tired nation was craving for a strongman who would restore order after years of chaos.

The structure of Russia’s economy, based on oil and gas revenues, also enhanced paternalism within Russian society (damaging the concept of the state as at the service of its people, who would finance the state with their taxes and feel the right to put forward their demands) and fueled the ambitions of its leadership. Finally, Russia’s nuclear arsenal fostered Putin’s sense of accountability as unnecessary: his rule inside Russia cannot be breached, and his aggression outside Russia’s borders cannot be challenged.

Yet eliminating Putin’s personality from this analysis would be incorrect. It would mean that Russia’s vicious path was predetermined.

In fact, Putin possessed a unique quality that made him very different from almost any other player who could theoretically have substituted for him as Yeltsin’s successor and Russia’s next president in the summer of 1999: he had no experience with the public political process. A career bureaucrat, he never took part in an election and never acted as a political person. His emergence as a head of government and the future leader of Russia in the summer of 1999 came as a shock first and foremost because it was totally unthinkable that this position—and this perspective—would be granted to an individual virtually unknown to anyone outside a small circle of Moscow bureaucrats and security officials. At that time, three Russians out of four didn’t even know his name.

Before becoming president, Putin never addressed voters at a political rally. Throughout his career, he never campaigned, did not take part in a single political debate. He propelled himself to national popularity with the help of television, and from the very start, television became his grandstand, his arena, his home.

From the first day of his rule, he connected with reality through staff memos and carefully assembled selections of news programs he watched in his car while on the way to the Kremlin or back to his villa. Human life, routinely reprocessed inside the enormous Kremlin propaganda machine, lost its value.

Pollsters and Kremlin watchers would later explain why Russians supported Putin’s wars: for them, the wars were virtual reality, television shows. Putin himself would be no different: as a leader, he never addressed people’s real hopes and aspirations, pains and sufferings; only their distorted and molded propagandistic projections. It was not people Putin was dealing with but their superficial image inside his mind, projected on a TV screen; a number from a public opinion poll; a reflection of his authority.

Bureaucrats respond to no one—but a political job is supposed to be open and transparent. Bureaucrats deal with papers, lists, and numbers—but a political job requires empathy. Paperwork is mechanical by nature—but political life is an organic process. It’s a form of social X-ray, a security check, that reveals the personalities of political leaders and filters out pathological forms. But Vladimir Putin was never a political leader. A clerk, he entered the heights of power through the back door and broke the system.

The opinions expressed in this article are those solely of the authors and do not reflect the views of the Kennan Institute.

Author

Russian Journalist and Filmmaker

Kennan Institute

After more than 50 years as a vital part of the Wilson Center legacy, the Kennan Institute has become an independent think tank. You can find the current website for the Kennan Institute at kennaninstitute.org. Please look for future announcements about partnership activities between the Wilson Center and the Kennan Institute at Wilson Center Press Room. The Kennan Institute is the premier US center for advanced research on Eurasia and the oldest and largest regional program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Explore More in The Russia File

Browse The Russia File

Chechnya as a Model of Modern Russia

Russia’s Indigenous Communities and the War in Ukraine

Gas and Power in a Changing US–Russia Relationship