A blog of the Wilson Center

“Right is right, and right don’t wrong nobody.”

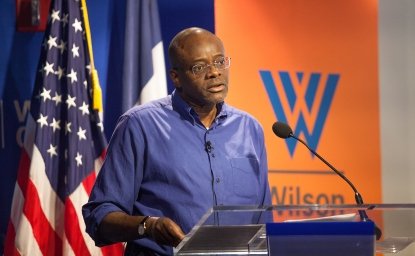

These words, from Dr. Maurice Jackson’s grandmother, shaped his personal ethos and his professional work.

Dr. Jackson’s journey to becoming a respected historian of African American life is both atypical and deeply personal. Born in Virginia, Jackson pursued many opportunities before becoming a scholar: he was a shipyard laborer, longshoreman, house painter, and community and human rights organizer. Despite the satisfaction he got from the hard labor of the shipyard, Jackson’s love for learning remained strong, and with one final push from his family, he was back at university. But his path to scholarship has always been grounded in the streets and communities he now dedicates his research to. Once back in academia, he earned his master and doctorate degrees, and became an associate professor at Georgetown University, where he focuses on African American history, the role of African American culture in Washington, DC, and the ways music and sports have shaped Black identity in the city.

He was a scholar for the Wilson Center between 2011 and 2012, and as he recalls it, “The Wilson Center gave me the space to really dig into my work.”

Being at the Wilson Center allowed him the freedom to connect with other scholars and refine his projects. "It was a place where you could get real, uninterrupted time to think and write," says Jackson. This support was crucial to the development of his research, allowing him to engage deeply in his subject matter and explore connections between history, activism, and political activity.

Another key theme in Jackson's scholarship, particularly in his book Rhythms of Resistance and Resilience, is the idea of resilience through culture. Instead of focusing on the grand, well-documented movements of formal activism, Jackson writes about the ways in which everyday people nurtured resilience, often through unexpected channels. He cites the example of James Reese Europe, a figure whose contributions to music and culture transcended the battlefield of World War I. Dr. Jackson recounted that James Reese was born in Mobile, Alabama, but attended Dunbar High School, the elite high school in Washington, DC, before serving in World War I. There, he not only fought but also introduced jazz music to European audiences through the Harlem Hell fighters' band, blending cultural expression with military service in a way that left a lasting impact.

But Jackson’s story isn’t just about the formal histories of notable figures. It’s also about the quieter personal acts of resistance that helped reshape the fabric of Black Washington.

“In 1939, Marian Anderson came to Washington,” Jackson stated. Anderson, an iconic artist of her time, was denied the opportunity to sing at Constitution Hall because of her race. Her story, however, wasn’t just about the rejection. It was about the power of activism in the form of music, and the solidarity that it inspired across racial lines. “Eleanor Roosevelt, the First Lady, then resigned her membership in the daughters of the American Revolution,” Jackson explained and reflected about how Anderson’s concert on the National Mall, in front of 75,000 people, became one of the most significant moments in the history of American civil rights.

As Jackson immersed himself in these stories, his passion for music became clearer. To him, music is not only a reflection of culture but also a means of resistance. Take Louis Armstrong, a man who, despite his fame, refused to perform abroad until the United States took action to protect Black children trying to integrate schools in Little Rock, Arkansas.

For Jackson, these stories of resistance go far beyond historical events—they speak to the ongoing struggles of Black communities in Washington today. Despite the city’s significant African American population, he sees an alarming trend in how the landscape of the city is changing. “Washington, DC, is probably more segregated now than it was 50 years ago,” he says, believing that the forces of gentrification are pushing longtime residents out and that with economic inequality worsening, the city’s Black community is being displaced from the very neighborhoods they helped build.

“There’s an attack on culture,” Jackson says, referencing the loss of spaces where Black culture once thrived. Places like the Bohemian Caverns and Twins, small community spaces where residents gathered, have been closed due to increasing rent prices. This ongoing struggle for cultural space is just one smaller manifestation of the larger systemic issues facing DC’s African American population.

Yet, Jackson doesn’t see this as a defeat. He remains a determined advocate for the survival of African American culture, and he calls on those in power to ensure that opportunities for success aren’t just for the few, but for all.

“It’s necessary for people of goodwill to come together to guarantee that African Americans are able to grow and prosper in this city,” Jackson says, continuing to state that despite having a Black mayor and a Black city council, the existing policies have not done enough to fight the challenges faced by Black residents.

Looking forward, Jackson’s work will continue to focus on the intersection of culture, history, and community. He has just completed Halfway to Freedom: The struggles and strivings of black folk in Washington, DC; a book he started to research while at the Wilson Center. As he teaches, mentors, and engages with his students, he encourages them to keep an eye on the larger societal implications of their work.

“It’s all about telling the right stories,” he says. “The stories that need to be told, that can inspire change and bring attention to the issues that matter most.” Through his work, Jackson wants to ensure that the stories of struggle and triumph are remembered, and that future generations can learn from the legacies of those who came before.

Author

Urban Sustainability Laboratory

Since 1991, the Urban Sustainability Laboratory has advanced solutions to urban challenges—such as poverty, exclusion, insecurity, and environmental degradation—by promoting evidence-based research to support sustainable, equitable and peaceful cities. Read more

Explore More in Scholar & Alumni Spotlight

Browse Scholar & Alumni Spotlight

Olufemi Vaughan: Shaping Governance Through Scholarship and Dialogue