A blog of the Kennan Institute

Armed incidents, the number of victims of violence, and the death toll connected with extremism have risen in Russia’s troubled republic of Chechnya in 2016 compared to 2015. And 2017 started with a large counterterrorism operation by the Chechen Ministry of Internal Affairs and the National Guard of the Russian Federation against an underground group accused of plotting terror attacks.

These events are indicative of a gathering accretion of home-grown extremist-minded and radicalized youth in Chechnya. The trend is related to the weakening of the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) as a territory-holding quasi-state and military group that until recently had absorbed many fighters from Chechnya. The Kremlin had declared the fight against ISIS one of its motives for intervening in Syria. An effective fight against ISIS, though, could ultimately create serious security problems at home in fragile Chechnya. Such a possibility triggers the question of whether the Kremlin will really fight ISIS in Syria and beyond.

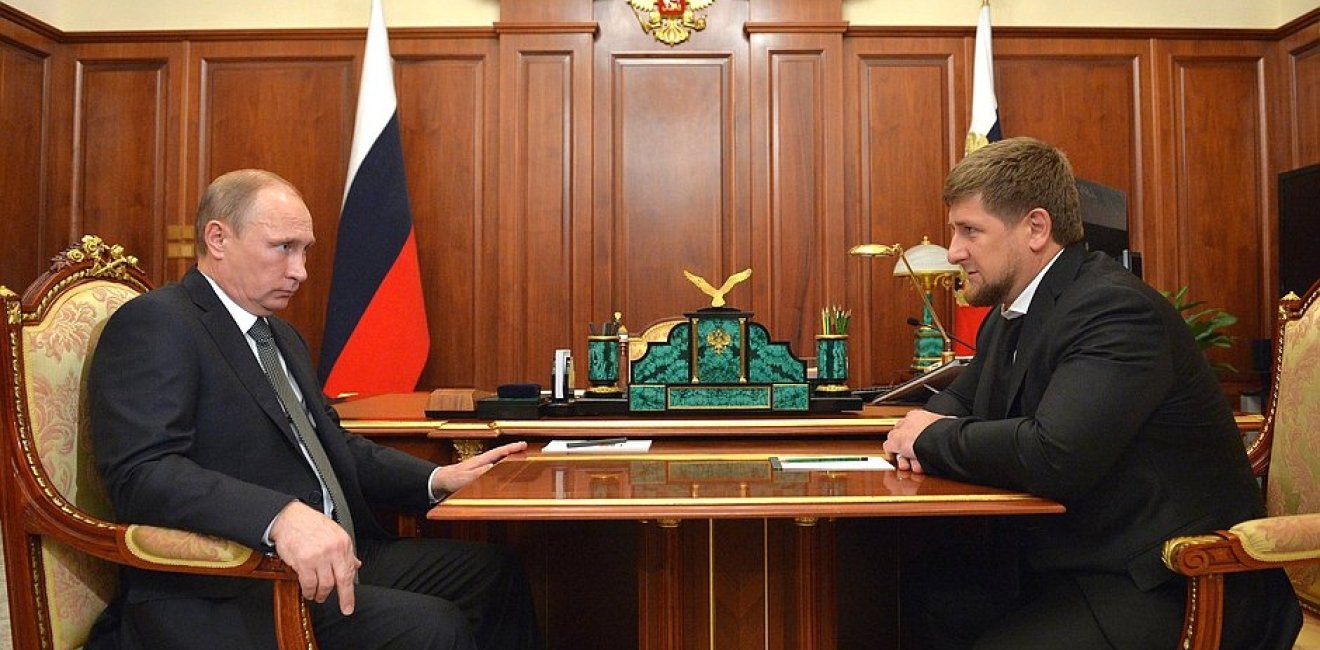

The number of victims and of those killed in the course of the armed conflict in Chechnya increased by 43 percent and 93 percent respectively in 2016 compared to 2015. The related armed incidents doubled in that period. It is not accidental that a large counterterrorism operation, of a scale unprecedented in recent years, was carried out in Chechnya over January 9–16, 2017. More than 60 members of a group linked to ISIS were arrested and four were killed in the operation. Two servicemen from the Russian National Guard were also killed during the operation. The governor of Chechnya, Ramzan Kadyrov, said that the entire group was controlled by someone in Syria who was originally from the Chechen town of Shali. He added that the underground group had been recruiting members for ISIS.

The Kremlin had declared the fight against ISIS one of its motives for intervening in Syria. An effective fight against ISIS, though, could ultimately create serious security problems at home in fragile Chechnya.

The outflow of potential fighters from Chechnya slowed significantly in 2016. The number of those who left Chechnya to join terrorists groups in Syria plummeted to just 19 in 2016, according to a source in the Interior Ministry of Chechnya. This figure is several times lower than the numbers for 2013, 2014, and 2015, which measured in the hundreds. Although the authorities attribute the drop in recruitment to the implementation of successful preventive and operational measures, the declining recruitment figures actually reflect the diminishing ISIS-controlled territories and ISIS forces in Syria and Iraq.

President Putin stated on February 23, 2017, that the number of Russian citizens fighting in Syria was approximately 4,000. Russia is the world’s third biggest contributor of fighters to ISIS and other extremist groups in Syria and Iraq. Among Russian regions, Chechnya is a major contributor to refilling the human capacity of the Islamic State. The Chechen outflow must be viewed in the light of certain controversial statements, such as “terrorism in Chechnya has been defeated.” The notional defeat of terrorism in Chechnya, however, is partly the result of Chechen fighters leaving for hot spots of radical extremism, mainly in Syria. The activity of the Caucasian underground was halved during the years of the Syrian war, and that fact is confirmed by law enforcement bodies, experts, rights activists, and residents of the region. Accordingly, the movement of fighters out of Chechnya can be thought of as an external solution to Russia’s domestic security problem.

The ongoing decline of ISIS in terms of territory and power, however, means that this external solution to Russia’s domestic security problem is becoming increasingly less operant. The decline of ISIS doesn’t necessarily mean the end of radicalization and recruitment in Chechnya. Possibly, radicalization and recruitment of youth by the Chechen underground will continue. This would potentially affect the security situation in two ways.

First, the return of experienced Chechen fighters from Syria, in conjunction with those already settled in Chechnya, may represent a bigger threat. This is not very likely, though, since Moscow has taken legislative precautions. President Putin stated in April 2015 that ISIS posed no direct threat to the country but that Russia was preoccupied with the fact that its citizens were joining ISIS and then returning home later. Under the October 2013 amendments to the Russian Criminal Code, the penalty for participation in terrorist activities abroad was increased. This effectively blocks those who intend to return home. Nevertheless, it is possible that some might try to return through a backdoor arrangement. In 2016, two Russian federal bills known jointly as the Yarovaya Law were adopted to amend the existing counterterrorism legislation. The Yarovaya Law was designed to block the backdoor entry as well.

Second, the accumulation of upcoming extremist-minded and radicalized youth at home in Chechnya may cause a serious deterioration in the security situation, with the potential for an upsurge in extremism. The rise in armed incidents, victims, and the death toll connected to extremism in Chechnya and the significant drop in the number of potential Chechen fighters leaving the country to join extremist groups in Syria in 2016 were early signs of that scenario taking shape. The counterterrorism operation of January 9–16, 2017, was essentially the authorities’ initiative to prevent that scenario from unfolding further.

“Despite the work we [authorities] have done, they [recruiters] managed to convince so many youth, who were ready to die for an idea they believe in, which is incomprehensible,” said the governor of Chechnya. The Chechen underground communities have constantly recruited such youth. But until recently they had been absorbed by ISIS on the battlegrounds of Syria and beyond. Currently ISIS’s significant loss of territories, its weakened positions, and the Mosul offensive all signal the looming decline of ISIS as a territory-holding quasi-state. Without a territory, the Islamic State will be hobbled in its ability to attract and accommodate potential fighters from Chechnya. Those potential fighters in turn are expected to become disheartened and less tempted to leave Russia to join ISIS abroad. This second scenario could result in the buildup of a population of potential fighters and radicalized youth at home. As a result, Russia may face a serious deterioration in its domestic security situation and even an uptick in extremism in Chechnya, which would be a nightmare scenario for Russia. Ongoing ISIS conflicts in Syria and elsewhere, on the other hand, could serve to drain radicalized youth from Russia’s territory, hence preventing that scenario. That is why it is hard to predict whether Moscow might wholeheartedly fight ISIS in Syria or anywhere beyond Russia’s borders.

Author

Kennan Institute

After more than 50 years as a vital part of the Wilson Center legacy, the Kennan Institute has become an independent think tank. You can find the current website for the Kennan Institute at kennaninstitute.org. Please look for future announcements about partnership activities between the Wilson Center and the Kennan Institute at Wilson Center Press Room. The Kennan Institute is the premier US center for advanced research on Eurasia and the oldest and largest regional program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Explore More in The Russia File

Browse The Russia File

Chechnya as a Model of Modern Russia

Russia’s Indigenous Communities and the War in Ukraine

Gas and Power in a Changing US–Russia Relationship