A blog of the Polar Institute

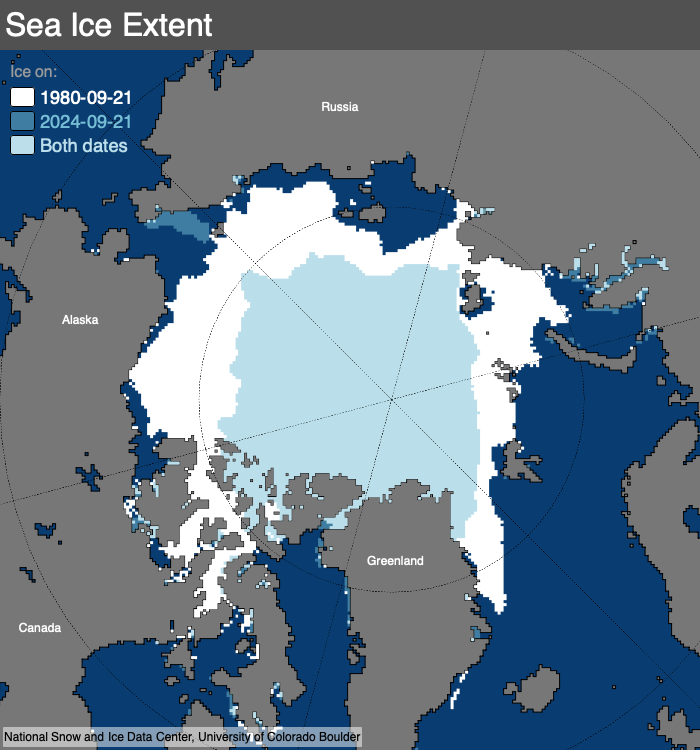

Arctic sea ice has been undergoing a transformation over the last 45+ years toward an eventual ice-free Arctic Ocean. Sea ice in the Arctic is much less extensive now, particularly during the late summer when the annual minimum ice cover is reached. It is also much younger on average, much of the ice just 2 or 3 years old, relative to the 1980s and early 1990s when a large portion of the ice was more than 5 years old. Older ice is thicker and more durable; but much of that ice was lost in a series of warm summers beginning in the late 1990s.

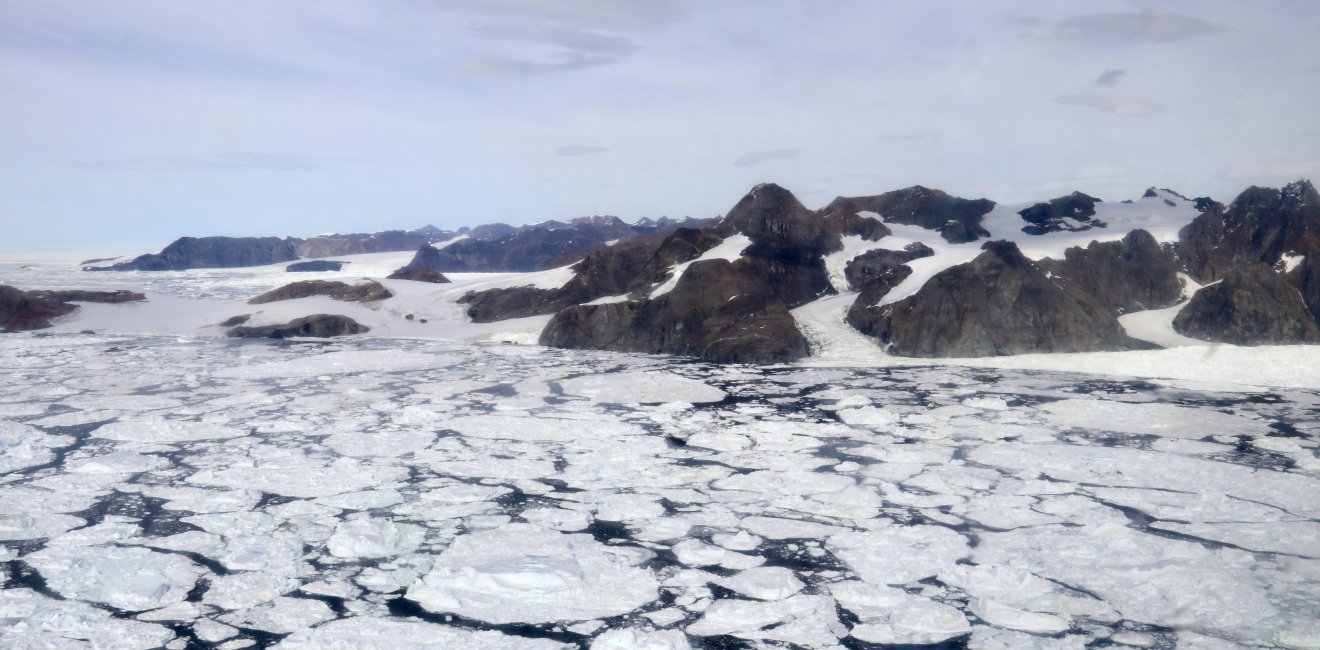

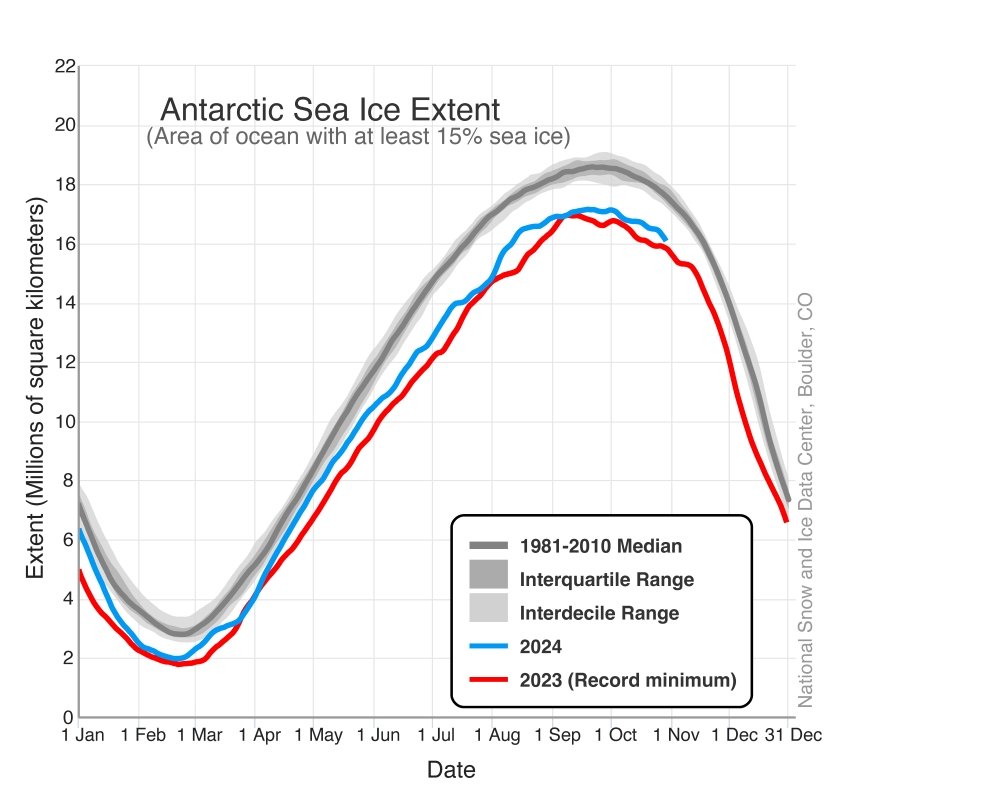

The picture in the Antarctic has until recently been much different, with regional variability and high year-to-year changes, but little trend. However, an apparent shift occurred in 2016 from generally higher than average ice cover to lower-than-average extent. Since 2016, there have been several record lows, including an extreme record low maximum extent in September 2023. The past year, and the recent maximum—again nearly as low as 2023— has reinforced these trends, although contrasts remain between the two poles.

The Arctic follows a pronounced annual cycle with extent reaching a maximum near in March of around 15 million square kilometers, and then declining to its annual minimum extent in September. In 2024, the monthly average September sea ice extent was 4.38 million square kilometers, based on satellite-borne sensors that began a consistent record starting in 1979. The September 2024 extent was the 6th lowest in that now 46-year satellite record. Since 1979, the September sea ice extent has declined by about 78,000 square kilometers per year or 12.1 % per decade relative to a 30-year baseline climatology spanning 1981-2010. Other months also show significant declines across all regions, albeit smaller in scope.

We have complete and consistent data on the surface extent of the ice, but we have much less information on the third dimension of the ice cover – the sea ice thickness. Over the long-term, the most complete indication of the thickness comes from tracking the age of the sea ice. Sea ice forms and grows through the winter and then either melts away during the subsequent summer or survives the summer. Ice that survives a summer melt season (called “multi-year” or “perennial” ice) continues to thicken through subsequent winters. So, for ice that has not been buckled under compression, older ice indicates thicker ice. In the 1980s, much of the Arctic Ocean was covered by ice that had survived at least four summers and was 3 to 4 meters thick. Since then, the Arctic Ocean has lost about half of its thicker multi-year ice and the really old ice (>4 years old) has nearly disappeared. The Arctic Ocean is now dominated by ice that has formed over just one winter (called “first-year” or “seasonal” ice) and is only 1 to 2 meters thick. Starting in 2010, satellite sensors have been launched that can be used to estimate thickness over the full Arctic Ocean. These thickness estimates show little trend since 2010, but indicate much thinner ice than seen in the 1970s through 1990s from submarine data.

Underlying the decline in Arctic sea ice extent is a trend toward warmer air temperatures in the Arctic. Since 1980, average air temperatures in the Arctic have increased 3 to 4°C, more than triple the global mean rate. The loss of ice cover adds to the warming, creating a self-reinforcing trend. In particular, the wide expanses of open ocean at the end of summer and into early autumn keep temperatures high much later into the cooling season than previously, and increase the amount of water vapor in the Arctic atmosphere.

Overall, the 2024 Arctic sea ice summer melt season was relatively moderate compared to recent years though extent remained far below earlier decades. While there were not extremes, there were some notable events. First, in the fabled Northwest Passage, sea ice almost completely cleared out. The wider and deeper northern route, conducive to shipping, reached a record low extent according to Canadian Ice Service analyses. The NWP has had several low ice years and has been largely open in late summer, though ice drifting into the channels of the passage can still impede navigation, even as there is less ice overall. Nonetheless, the NWP environment has fundamentally changed since the 1980s and earlier decades. An expedition led by Roald Amundsen from 1903 to 1905 was the first ship to successfully traverse the NWP, requiring nearly three years due to the ice conditions. In recent summers, numerous ships have sailed through the passage over the course of a few weeks or less.

Another notable event in the Arctic summer melt season was an extremely early retreat of ice in the eastern Hudson Bay. Normally, Hudson Bay starts to open in late June and initially in the western side of the bay. However, this year ice loss began in early May – on the eastern side. This was due primarily to strong easterly winds that pushed the ice from the east toward the western shore, leading to record low Hudson Bay extent from mid-May through much of June. Ironically, this led to a later than normal ice loss in the west. The winds that cleared out the ice in the spring piled up ice along the western shore, which was able to survive longer through the summer warmth.

A third feature observed in 2024 was substantial open water at the North Pole. Some open water at the pole has always occurred due to ice shifting with the winds and currents that cause the ice to fracture opening up narrow ice-free areas, called “leads”. But these leads would be narrow (100s of meters to maybe a few kilometers wide) and occur as a small percentage (<5%) of the total area amid a thick, consolidated ice pack. But by August 2024, as in other recent years, the pole was characterized by loose floes of ice amid substantial open water. Sea ice was still predominant, but it was it was not the solid, consolidate sheet of ice as in the past, and was more like crushed ice melting in a glass of water. Similar conditions in 2020 allowed an icebreaker to cruise to the pole with almost no resistance.

Yet another quirky feature of the 2024 Arctic sea ice summer was an area of persistent “dirty” ice between the Siberian coast and Wrangel Island, just to the northeast of Alaska. The 100,000 square kilometer area of ice was notable for a brownish-gray “dirty” looking surface in visible imagery. The ice appears to have formed from strong and persistent spring winds from the east and south that wedged ice between the Siberian mainland and Wrangel Island, compressing it together and piling it up into thick “ridges” of ice. The dirty appearance likely came from the thick, ridged ice scouring the bottom of the shallow shelf region and bringing sediment to the surface and/or from bottom algae that was overturned from the piling up of the ice. Much of this “chunk” of ice survived through the summer even though a good part of it was south of 70 degrees North latitude, while in all of the surrounding area and several hundred kilometers to the north melted out completely. While there was some melt through the summer, at least 60,000 square kilometers of ice survived to the fall freeze-up. It appears that this ice is the lowest latitude surviving ice of that size in the Arctic in at least several years.

Moving south to the Antarctic, 2024 would have been a stunningly low extent year…. were it not for the previous record low year of 2023. In 2023, the Antarctic extent reached a record low minimum extent in February, surpassing the previous lowest summer minimum by nearly 200 thousand square kilometers. The ice growth from the minimum through the early austral autumn of 2023 was typical until May when the growth rate slowed dramatically before reaching a stunning record low maximum extent in early September 2023, over one million square kilometers below the previous record low maximum. During 2024, extent was also extremely low, below all previous years in the satellite record except 2023 for much of the year. This was particularly true between June and October 2024, the period when the ice edge reaches its farthest extent northward in the Southern Ocean. During the autumn and winter, the growth slowed such that 2024 extent nearly matched 2023 levels.

In the end, the 2024 maximum extent was 17.16 million square kilometers, second lowest in the record, just above the 2023 maximum. This slowing of the ice advance relative to previous years, and the hastened retreat in spring and summer, has let the polar sea ice science community to suspect that warmer ocean conditions in the surface and upper ~10 meters of the ocean (the ‘mixed layer’, mixed by wind and waves) is the cause of the regime shift. Surface air temperature anomalies are large, warm where the ice is retreated; but similar air temperature anomalies have occurred in the past without such a dramatic sea ice retreat. Conversely, much of the world’s ocean surface is at record warm temperatures, and indeed, the areas where the anomalously low sea ice conditions are worst are regions just south of warm surface ocean conditions.

Overall, Antarctic extent has largely been lower than normal since September 2016 with several periods of record low extent. This is a significant shift from pre-2016 conditions where Antarctic sea ice extent had a small long-term increasing trend and had hit record high maximum extents in 2013 and 2014. There is an indication that this change represents a “regime shift” toward a new state of low Antarctic extent that is likely related to increased ocean heat in the upper Southern Ocean that is hindering growth and facilitating earlier retreat melt. While Antarctic sea ice appeared to be largely insulated from the overall warming trend, this regime shift may be an indication that global warming, and particularly warm near-surface ocean waters, may finally be affecting Antarctic sea ice.

The sea ice environments in both the Arctic and Antarctic are dramatically changing. In the Arctic, the change has been a persistent decrease in the coverage and a thinning. In the Antarctic, the change has come more recently, but the regime shift within the past decade has been pronounced. Now, sea ice at both poles appears to be responding to the warming temperatures.

Authors

Polar Institute

Since its inception in 2017, the Polar Institute has become a premier forum for discussion and policy analysis of Arctic and Antarctic issues, and is known in Washington, DC and elsewhere as the Arctic Public Square. The Institute holistically studies the central policy issues facing these regions—with an emphasis on Arctic governance, climate change, economic development, scientific research, security, and Indigenous communities—and communicates trusted analysis to policymakers and other stakeholders. Read more

Explore More in Polar Points

Browse Polar Points

Melting Point: Where is the Antarctic Sea Ice?

Greenland’s New Governing Coalition Signals Consensus