Q: Describe your background and what brought you to the Wilson Center.

I was supposed to come to the Kennan Institute in the summer of 2020, but we all know how events beginning in March made that impossible.

Since graduate school I have been an academic nomad, teaching at NYU, Brown, Columbia, and NYU-Shanghai. Before graduate school I spent a few years in Russia, mostly in St. Petersburg, studying and working. I was initially attracted to Russia and Eurasia out of a fascination with communism, but once I arrived in Russia my interest became more-or-less equally split between understanding the former Soviet Union and its cultures with their centuries-old histories and understanding how the Marxist experiment impacted people’s lives and world views.

My scholarship has consistently been about how major political events play out on the ground – how a variety of people experience events of unimaginable scale on a personal level. This has led me to write about subjects such as material culture, gender, and nationalities’ policy. I arrived at grad school thinking I would write about ethnic minorities in the Red Army and ended up writing about the experience of Red Army soldiers during the Great Patriotic War through stuff. I purposefully highlighted the voices of “non-Russian” soldiers and women, but the book was more focused on examining how the experience of using similar objects brought together a diverse array of people and changed how they thought about themselves and the state that they defended. As I was finishing the book, I applied to the Kennan Institute to work on my second monograph.

Q: What project are you working on at the Center?

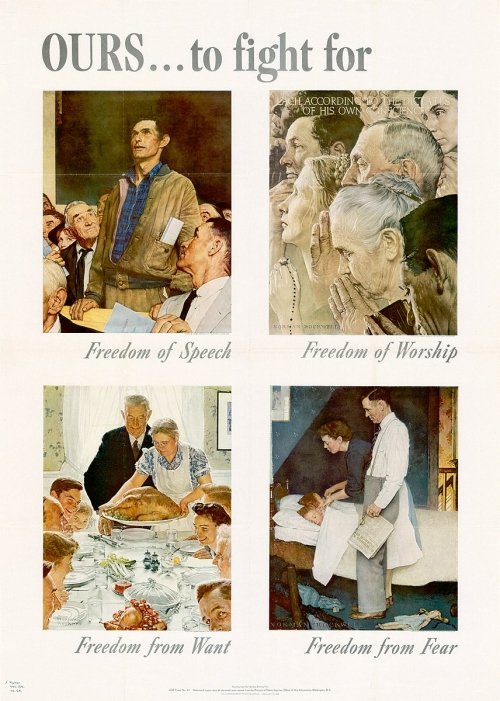

The Search for Salvation in the Second World War looks at how the US and USSR, two very different regimes – a liberal, pluralistic democracy and a monolithic dictatorship – tried to help soldiers answer the existential questions that came with fighting a global war of unprecedented scale and carnage. It did this by embedding specialists among soldiers who represented the core values that each regime was defending. In the case of the US Army, this function was served by the Chaplaincy, while the Soviets drew on political workers. These specialists lived among soldiers, explaining why they were being asked to make such extreme sacrifices, organizing the celebration of holidays and rituals of burial. They also provided what I think is best described as pastoral services – if soldiers received bad news from home or had interpersonal issues within the unit, the chaplain or the political worker was supposed to offer guidance. This could be anything from unfaithful spouses, connecting soldiers with their families, or whether or not to get married, to how to come to terms with the deaths of loved ones.

It has been a lot of fun to research, because you get to see how two very different societies come to grips with the same problems – sometimes in ways that are startlingly similar, sometimes in ways that couldn’t contrast more. As a preview of the latter, one thing that both sets of specialists had to do was sanction violence. For chaplains this could be somewhat problematic, given the Sixth Commandment (“Thou shalt not murder/kill”). Chaplains tended to emphasize that there were great warriors in the Bible, and that the tasks of the soldier were similar to those of the policeman in peacetime – protecting innocent people from criminals. The chaplaincy was averse to hate speech and spoke of the enemy as someone led astray who could be brought back to the light. In contrast, hatred was central to political work in the Red Army, where soldiers bore witness to mass atrocities committed by the Nazis. Killing the enemy was a civic duty that proved your love of country and kin and hatred of the enemy a sacred emotion. Chaplains were non-combatants forbidden from carrying weapons, while a political worker’s authority was often based on their proficiency with weapons.

Now despite this dramatic difference, the day-to-day activities of chaplains and political workers could be quite similar. If chaplains held regular religious services, political workers held meetings. Both wandered around their unit talking to soldiers, getting to know them and offering counsel. Both spread information about events around the world and within the unit. Both distributed extra goodies to soldiers and both served as the human face of a massive, impersonal institution.

Q: How did you become interested in your current research topic?

It came rather organically out of a combination of the research I was doing and geopolitics.

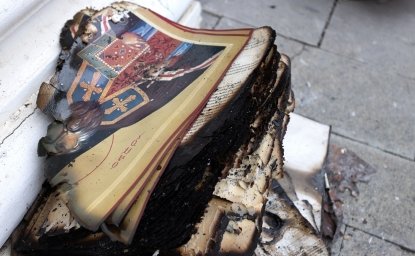

My first book, The Stuff of Soldiers (Cornell, 2019) tells the story of the Red Army in the Second World War through material culture – everything from spoons to tanks. My research drew heavily from the Party Archives and materials produced for political work. Political workers in the Red Army were responsible for ameliorating constant shortages of material and a lack of training among soldiers throughout the war. Once they lost their command function in the fall of 1942, making sure that soldiers were materially well taken care of and spreading information about how to properly use their weapons and equipment were key to their work. By the time I finished Stuff of Soldiers, I had come to know the Political Directorate of the Red Army quite well and realized that there wasn’t a solid English-language treatment of this important institution during the war.

I found a few Soviet memoirists who explicitly compared the work of a good political worker to that of a chaplain and I was sold on the idea. It also didn’t hurt that my dissertation advisor was working on a book that argued that the Bolsheviks were essentially a millenarian sect (Yuri Slezkine, The House of Government) and I was steeped in discussions of Bolshevism as something like a religion.

Geopolitics stepped in twice. Until 2014, I planned on getting a job at a university in St. Petersburg or Moscow and thought that being able to teach courses in American History would be attractive to the type of institutions I wanted to work at. This led me to take a secondary field in US History in grad school, where I was a teaching assistant in courses in US history more than any other subject. The idea to make the second book comparative emerged from this and conversations with friends who worked on US religious history. After 2014, while I continued to go to Russia, it was clear that access to archives might become an issue and that it was no longer tenable to plan a future there, so having a project where the archives I hadn’t yet mined were in the same country that issues my passport became a plus.

Q: Why do you believe that your research matters to a wider audience?

I try to offer a wider audience two things: an explanation of the origins of some modern tropes and an understanding of events of incomprehensible scale on a human level.

Both how the US imagines it role in the world and the primary framing of Russia’s current war in Ukraine emerged from the Second World War. The US went from a country that was (at least rhetorically) isolationist to one in which international intervention was considered a necessity to the securing of freedoms at home. The Soviet project had always been global, and the war gave opportunities for expanding communism, but the regime was nearly toppled in 1941-1942. The Third Reich (and to a lesser extent Imperial Japan and Fascist Italy) provided a model of an enemy who was so alien and dangerous as to require a total commitment to victory, one that was credible to Soviet citizens early in the war and became credible to Americans as news about concentration camps spread. For the Soviets, the Third Reich was simply the most pure and honest form of capitalism – a proudly imperialist society so obsessed with its own right to acquire things that it happily killed and enslaved its neighbors. The US was a proudly capitalist country, and the UK proudly imperialist, so Soviet leaders expected more of the same in the postwar period. For the US, a model of totalitarianism being key to explain Axis behavior, that is, essentially, a society that puts the state before God, destroying individual dignity and making a messiah figure of the leader. It was easy for people in the US to shift this framing from the Third Reich to the Soviet Union. In the early Cold War, we can see the tropes developed to describe Axis powers being deployed against former allies, alongside a call for formal religious affiliation as a sign of loyalty to the American way of life in the US, and in the Soviet Union a return to orthodox Stalinism after a period when the state lost control over many of its citizens. Fast-forward to today and Putin has shifted the narrative of the Third Reich from being distillation of capitalism to it being the purest form of an eternal “Western” hatred of Russia as a civilization. While the US is defending and trying to hold onto the order established in the wake of the Second World War. This book will tell the story of how these tropes were transmitted – and in some ways authored – by specialists embedded among soldiers waging the Second World war – chaplains and political workers.

This brings me to the second thing I want people to take from the book: I will be telling this story largely from the perspective of people on the ground. While I will talk about high-level decisions made in the Office of the Chief of Chaplains and the Political Directorate of the Red Army, my main emphasis will be on the day-to-day interactions of individuals. This is why I emphasize the pastoral work of both sets of specialists. How did soldiers’ interactions with people very different from them – Americans in Europe, the Pacific, India, etc., Red Army soldiers in East Central Europe – change how they saw themselves and their society’s place in the world? How did chaplains and political workers help soldiers interpret villages massacred by the Nazis and concentration camps? And how did these specialists help maintain ties with loved ones back home (as defending home became a central framing of why soldiers were being asked to make such tremendous sacrifices)? My work has always been about how major policies play out on the microlevel and how understanding the microlevel helps us understand macro processes, and here I aim to do the same.

Q: What is the most challenging aspect of your research?

Two things: being disposable labor and COVID.

I was scheduled to be here two years ago, instead I ended up in Shanghai teaching students who were supposed to be in the US but couldn’t come due to the pandemic. I was supposed to be gone for a semester, and ended up staying sixteen months. In Shanghai I met wonderful people and had a lot of conversations that forwarded the book, but I was away from my sources until 2022.

But the greatest challenge by far in realizing my work is the job market. I have been disposable labor since I finished graduate school, so I spend much of my time trying to piece together employment with no permanent institutional home and no sense of whether I will have the resources to finish the book.

Q: What do you hope the impact of your research will be?

I hope that this will contribute to our knowledge of how the Second World War changed how both states and citizens understood their place in the world, add to our understanding of the early Cold War, and enrich our understanding of how both the US and Russia imagine and have imagined their place in the world since the 1930s.

The opinions expressed in this article are those solely of the author and do not reflect the views of the Kennan Institute.

Author

Visiting Scholar, Jordan Center for the Advanced Study of Russia, New York University; Teaching Resource Developer, "Teaching Things: Material Culture in the History Classroom," American Historical Association

Kennan Institute

The Kennan Institute is the premier US center for advanced research on Eurasia and the oldest and largest regional program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region though research and exchange. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Who Owns Tradition? Ukraine’s Church Controversy

The Two Layers of Alexei Navalny