This has been a summer of discontent in Washington best symbolized by the region’s collapsing metro. In addition to large sections of system being shut down for too-long deferred maintenance, one major station – Cleveland Park – was recently flooded following an intense but hardly rare outbreak of thunderstorms. National politics, the city’s biggest industry, has become a dystopia of theorists’ nightmares; and even in local politics three of Mayor Bowser’s stalwart allies on the city council went down to ignominious defeat in party primaries. Even the iconic Capitol Dome is under scaffolding during much needed repairs.

What is going on? There are many explanations, of course, but one is simply that Washington has become a city. Cities constitute humankind’s largest and most complex products and, like all human inventions, are given to failure over time. Washington, as a planned city, more often than not is thought of as a symbol rather than a place; and certainly is talked about in American national discourse as such. Yet, at some point, Washington like all planned cities eventually just became a place.

Washington is a special kind of city, the planned new capital. Vadim Rossman, in a superb encyclopedic new book -- Capital Cities: Varieties and Patterns of Development and Relocation -- chronicling the history of planned capitals (they are everywhere having been built ever since politicians needed a place to be) argues that new capitals are only as successful as the political regimes which build them. Moreover, at a certain point the new becomes the old; and capitals become just cities. Washington is now past that point.

There is, of course, no fixed moment when a new capital becomes a city. In some instances, such as St. Petersburg and Washington, the process required a couple of centuries. Why so long? Because there needs to be sufficient lived life to take abstract places set down in plans detached from any local reality to take hold. Perhaps there is a need for all memory of the founding moment to have been lost to living memory, requiring the grandparents of city dwellers to have become familiar with the capital as a place and not a plan. More important, it requires that all sorts of institutions take hold which would sustain a city even were the capital to leave.

St. Petersburg is a case in point. The Bolsheviks moved their capital to Moscow almost a century ago and St. Petersburg remains the fourth largest city in Europe. The Soviets still needed the educational, cultural, and, most importantly, industrial enterprises that had emerged in St. Petersburg even after its “true” function as a seat of power had come to and end.

Despite all the commentary suggesting that “Washington” is “broken” and the country would be better off without it, Washington would not disappear were the capital to move to, say, St. Louis. This was not the case in the nineteenth century when such proposals gained traction for a while. However, at a minimum, the region’s half-dozen major research universities and many more additional smaller colleges would remain. They simply would be too expensive to leave. Like St. Petersburg’s industry, much of its economic power would remain, though certainly in muted form.

Washington may be an unhappy town at the moment, but hardly more or less so than many other cities around the world. Cities created as Washington was out of whole cloth are human inventions just as their more organic cousins port cities and market towns are. At some point, cities just stop being new. Perceptions, however, always lag.

Naples, Italy, is so old that few remember that its name came from the Greek for “New Town.” Founded as a Greek colony, Naples was the sort of colonial new town that we think of as being somehow more pure and rational. Yet, “the wonder of the place,” as the novelist and writer on the arts Benjamin Taylor reminds us in Naples Declared: A Walk Around the Bay, “is that it has not been annihilated by so much history. Ask yourself what New York or Chicago or Los Angeles will be twenty-five centuries from now. Imagination falters.”

Looking at images of water streaming into Washington metro stations during this summer of discontent, the imagination indeed falters in thinking what the city would be like twenty-five centuries from now. Meanwhile, Washingtonians are reaching for the pails to bail themselves out.

Author

Former Wilson Center Vice President for Programs (2014-2017); Director of the Comparative Urban Studies Program/Urban Sustainability Laboratory (1992-2017); Director of the Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies (1989-2012) and Director of the Program on Global Sustainability and Resilience (2012-2014)

Urban Sustainability Laboratory

Since 1991, the Urban Sustainability Laboratory has advanced solutions to urban challenges—such as poverty, exclusion, insecurity, and environmental degradation—by promoting evidence-based research to support sustainable, equitable and peaceful cities. Read more

Explore More in Building Inclusive and Livable Cities

Browse Building Inclusive and Livable Cities

Hometown D.C.: America's Secret Music City

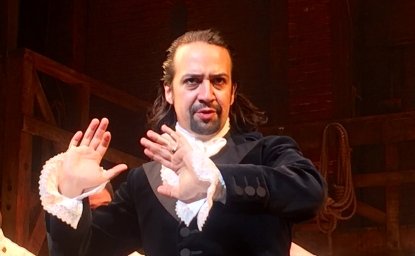

Bringing New York to the Broadway Stage

10 Steps to a More Genuine DC Experience