A blog of the Kennan Institute

Seeming frenemies: Why Belarusian-Russian relations remain more predictable than they appear

For the last several months we have been watching yet another episode of the Russian-Belarusian drama. For a couple of months in a row it seemed to several observers in the West that Moscow-Minsk relations were entering a new phase of confrontation, with both President Lukashenka repeatedly voicing harsh criticism of Russia and its policies toward Belarus and various politicians and media in Russia warning Belarus of “following in Ukraine’s footsteps.”

The Russia media even went so far as to speculate on a possible successor to Lukashenka, while the president of Belarus firmly denounced a “possible” incursion of “little green men” – Russian soldiers – into Belarusian territory. This exchange led some in the West to proclaim that Moscow and the West were swapping positions on Belarus, implying that the ongoing conflict might considerably change the existing status quo in the Western-Belarusian-Russian relationship configuration.

Indeed, back in February it seemed that Russian-Belarusian relations had hit a new low, with Belarus introducing five-day visa waivers for the citizens of 79 countries, including the U.S. and EU member states, and Russia in response reintroducing border checkpoints without prior consultation with its Belarusian counterparts. Moreover, Lukashenka was refusing to sign the new Customs Code of the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), which had been introduced at the summit of the Supreme Council of the EEU in late 2016. (The Belarusian president was the only Eurasian head of state to miss that session in December.)

The Russia media even went so far as to speculate on a possible successor to Lukashenka, while the president of Belarus firmly denounced a “possible” incursion of “little green men” – Russian soldiers – into Belarusian territory.

Still, the bigger problem for Russian-Belarusian relations was the price of gas. For years, Russia had had a special deal for Belarus, essentially subsidizing the gas price, but in 2016 Minsk unilaterally lowered the price it was paying, which, according to Russia, led to the accumulation of $780 million in debt. In a tit-for-tat response, Russia reduced the supply of duty-free oil from the agreed-upon 24 million tons to 18 million tons a year. Since oil reexports account for a significant share of Belarus’s earnings, this move led to massive frustration and mutual criticism.

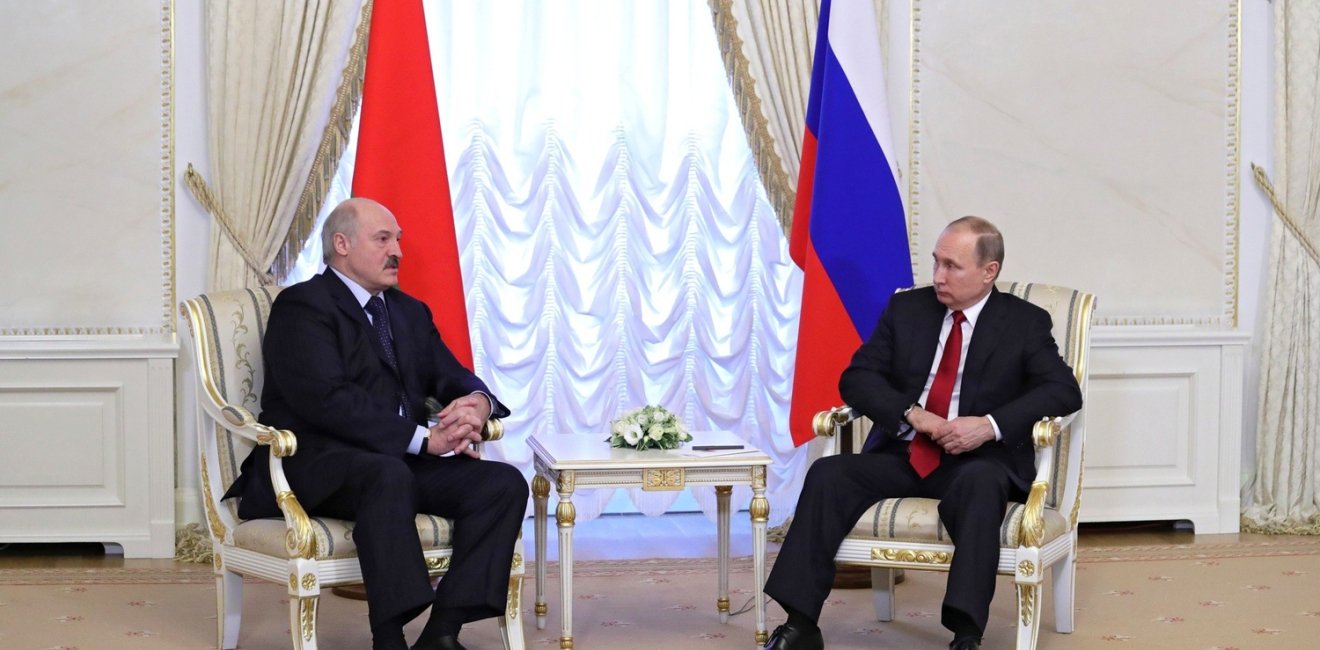

Since January 2017, Lukashenka has been trying to meet Putin in person to negotiate a resolution to the emerging conflict. In February there were numerous reports of upcoming meetings, but all of them were subsequently delayed indefinitely. Lukashenka even went to the Russian ski resort in Sochi for a week, but Putin denied him an audience. The two met only in early April, thereby ending speculation, with a compromise on the gas price and a $1 billion loan from Russia that would help stabilize the Belarusian economy. A week later Lukashenka signed the EEU Customs Code.

Once again, Lukashenka has proved to be politically savvy enough to get what he wants from Russia while continuing to build his reputation in the West of being tough on Putin. Ever since the annexation of Crimea, the risk of being seen as an ally of Russia has grown higher for Belarus, but it seems that Minsk has been able to institutionalize its “unique” relationship with Russia, whether through hosting the Minsk peace talks on Ukraine or making the West soften its stance on the “former last dictator of Europe,” to the point that the West thinks it is its idea to initiate rapprochement with Belarus.

It is true, however, that close relations with Russia no longer guarantee significant economic growth for Belarus, as the country suffers every time the Russian economy slows down. Moreover, the promise of Eurasian integration no longer guarantees any significant economic benefits. In fact, Minsk does not need the EEU to get credits and gas discounts from Moscow. It allows the EEU to continue to “develop” not because doing so serves the interests of the Belarusian economy or the country’s political goals but because it pleases Moscow by continuing the so-called integration process in the post-Soviet space, which is very important for Moscow. But, as Moscow holds almost every key to Belarusian economic well-being, Minsk cannot simply attempt to cut the ties to Moscow and pivot to the West, beyond the rhetoric that the Kremlin is allowing, even if Minsk wanted to.

The West should clearly understand that there are limits to how far Belarus can move away from Moscow and that most of the time, Lukashenka’s rhetoric must be put in the context of ongoing negotiations with Moscow. This leads to several straightforward conclusions:

1. The “uniqueness” of Belarusian-Russian relations now rests in Belarusian economy’s high dependency on Russia rather than in any shared vision of future, whether it be “Eurasian integration” or simply “authoritarians united.” It may seem easy for Belarus to turn away from Russia should circumstances demand it, but as long as Moscow supplies what Belarus needs, this is unlikely to happen.

2. There is a very easy way to check whether Lukashenka is serious in his criticism of Russia. He follows the same rules that the Russian opposition has followed for years: you can criticize the system, its institutions, and particular bureaucrats and politicians as long as you don’t criticize Putin personally. If and when that does happen, we could safely assume that real changes are on the way.

3. Despite the harsh rhetoric that Belarus allows itself to emit, as long as Minsk does not change the basic framework of its relations with Russia, Moscow will never consider sending the infamous little green men or “saving” the Russian-speaking population in Belarus in any other way. Thus any speculation about a possible Russian military incursion should be taken with a decent grain of salt.

It is impossible to predict how Belarusian-Russian relations might look after Putin and Lukashenka, but for as long as those two are in power, they will be able to find a common language, despite the occasional seeming estrangement.

Author

Editorial Director, Riddle Russia

Kennan Institute

After more than 50 years as a vital part of the Wilson Center legacy, the Kennan Institute has become an independent think tank. You can find the current website for the Kennan Institute at kennaninstitute.org. Please look for future announcements about partnership activities between the Wilson Center and the Kennan Institute at Wilson Center Press Room. The Kennan Institute is the premier US center for advanced research on Eurasia and the oldest and largest regional program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Explore More in The Russia File

Browse The Russia File

Chechnya as a Model of Modern Russia

Russia’s Indigenous Communities and the War in Ukraine

Gas and Power in a Changing US–Russia Relationship