A blog of the Science and Technology Innovation Program

As more industries and policy makers around the world awake to the transformative benefits that artificial intelligence (AI) could bring to our lives, two countries, the United State and China, appear to advance ahead of the others in AI research and development. This piece seeks to provide a first snapshot of the general state of AI research and development in these two countries through comparing AI-related patenting trends.

Patent statistics are used extensively in economic analysis as an indicator to interpret long-term trends in technological change[1]. According to the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) PATENTSCOPE database, 3,054 patents on artificial intelligence were filed between 2007 and 2017 (as of February 16, 2017)[2]. Of those patents 1,030 were applied for in the United States; 674 in the People’s Republic of China (China); 467 in the Republic of Korea (ROK); and the remainder applied with PCT (the Patent Cooperation Treaty)[3], the European Patent Office and other national/regional patent offices. With these numbers it is possible to say where invention is occurring.

For readers unfamiliar with AI, the majority of technologies can be grouped into one of three areas listed below. In the WIPO classification system that is: G06F – electric digital data processing; G06Q – Data processing systems or methods, specially adapted for administrative, commercial, financial, managerial, supervisory or forecasting purposes; and G06N – Computer systems based on specific computational models. Within these three categories the distribution is: G06F – 1056, G06Q – 579, and G06N – 519. Out of the total 3,054 patents, 2,154 or 70.5% are grouped under the broader category of “physics: computing; calculating; and counting.”

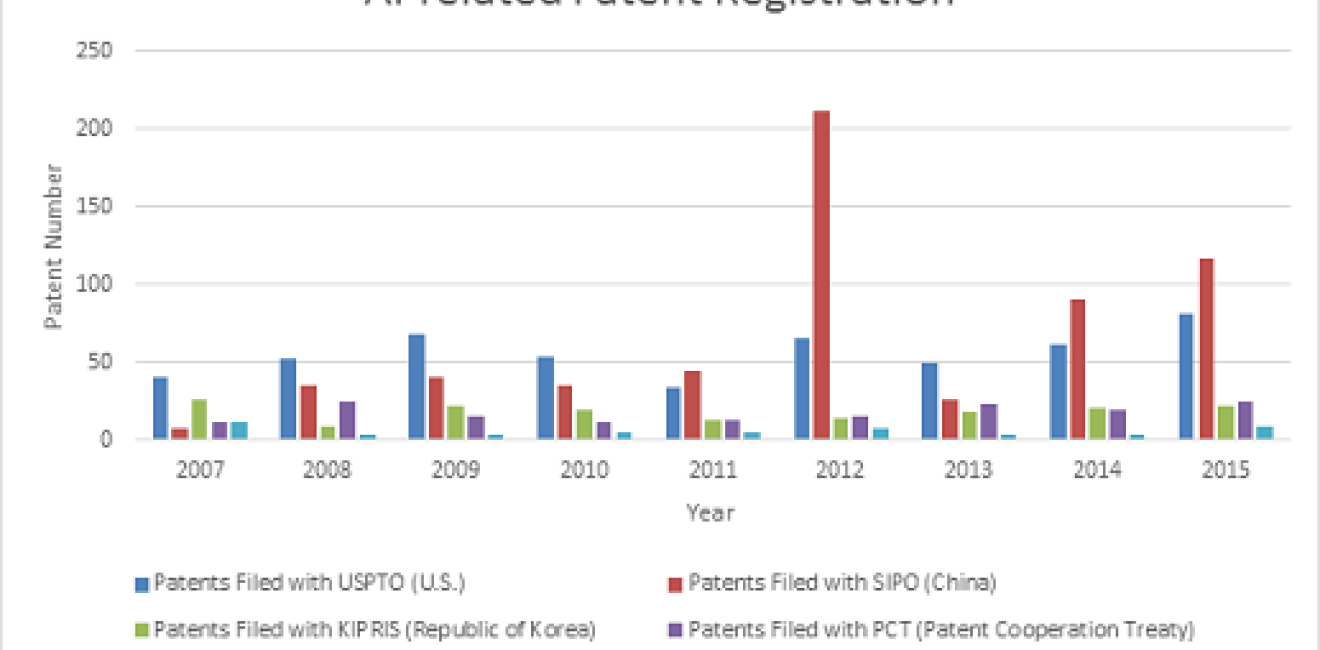

Next we look at the trend of AI-related patent registration with different national/regional patent offices over time between 2007 and 2015 (the most recent year when patent data for all major countries are available). Using the PATENTSCOPE database, we could see the U.S. taking the lead in the number of AI patent registration since 2007, but China catching up and surpassing the U.S. in 2011, 2012, 2014 and 2015 (see the graph above). A calculation of the annual growth rate for patent registration shows that AI-related patent registration grew much faster in China than the U.S. and other major countries/regions. The Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) for AI-related patent registration between 2007 and 2015 is 39.8% for patents filed in China, compared with 9.6% for patents filed with the Patent Cooperation Treaty, 9.2% for patents filed in the U.S., -2.1% for patents filed in the Republic of Korea, and -2.5% for patents filed with the European Patent Office.

While the patenting trends show China as a strong competitor to the U.S. in the AI research field, there are some caveats for using patent data to measure the rate of innovation in a country:

First, patents can be filed in a country by either residents or nonresidents (aliens). For instance, a patent filed with SIPO (State Intellectual Property Office) of China can be the result of an invention by either a Chinese firm or a foreign firm seeking protection in the Chinese market. Therefore, the rapid increase in patent registration in China could be the result of both increases in patent registration by domestic Chinese companies/nationals and increases in patent registration by foreign companies/nationals seeking protection in the Chinese market.

Secondly, differences in government policies can lead to differences in the practice of patent granting. In the case of China, the National Patent Development Strategy (2011-2020)[4] has set ambitious targets for the annual quantity of patent applications and explicitly calls for government incentives to increase the number of domestic patent filing. Thus minor improvements in existing product design or technology have been reported to be more likely to be granted patents in China compared to other countries including the United States[5].

Thirdly, increase in the quantity of patents do not automatically equate with increase in the impact of innovation. If we look at the process of technological change from the invention to the end result of the product, then patents only capture the early part of the innovation process. A subpar innovation system could render many patents dormant without making to the end stage of commercialization.

The key insight of these figures is that Chinese companies are becoming more innovative. Other measures such as market capitalization or gross expenditures on research and development may offer a somewhat different perspective. However, this measure of technological progress shows that the Chinese market is becoming more competitive in artificial intelligence technologies. If and when there will be a parity in value-added to the U.S. in artificial intelligence technologies is a topic still up for debate.

[1] Zvi Griliches. (December 1990)."Patent Statistics as Economic Indicators: A Survey." Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XXVIII, pp. 1661-1707.

[2] The search is conducted in the WIPO PATENTSCOPE database (http://www.wipo.int/patentscope/en/) using “artificial intelligence” which appears on the front page of a patent document as the search criteria.

[3] The Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) allows applicants who are residents or nationals of PCT contracting states to simultaneously seek protection in all 151 contracting states by filing one “international” application (http://www.wipo.int/pct/en/pct_contracting_states.html). However, the granting of national patents remains under the control of the national or regional patent Offices, and applicants need to fulfill the corresponding requirements (for instance, paying national legal fees, filing translations of the application) to be granted patents in countries or regions where they seek protection. For more information, see http://www.wipo.int/pct/en/faqs/faqs.html.

[4] State Intellectual Property Office (SIPO). (2010). “National Patent Development Strategy (2011-2020)”. Retrieved from http://graphics8.nytimes.com/packages/pdf/business/SIPONatPatentDevStrategy.pdf

[5] Anil K. Gupta and Haiyan Wang. (2011, July 28). “China as an Innovation Center? Not So Fast”. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424053111903591104576469670146238648

Authors

Science and Technology Innovation Program

The Science and Technology Innovation Program (STIP) serves as the bridge between technologists, policymakers, industry, and global stakeholders. Read more