A blog of the Kennan Institute

Russia’s twenty-first-century propaganda machine for Western consumption had a mighty precursor, PR operations set up in Berlin in the late 1920s by a little-remembered German communist. The effort of today’s Moscow to sell its story to the world is not nearly as successful as Stalinist Russia’s.

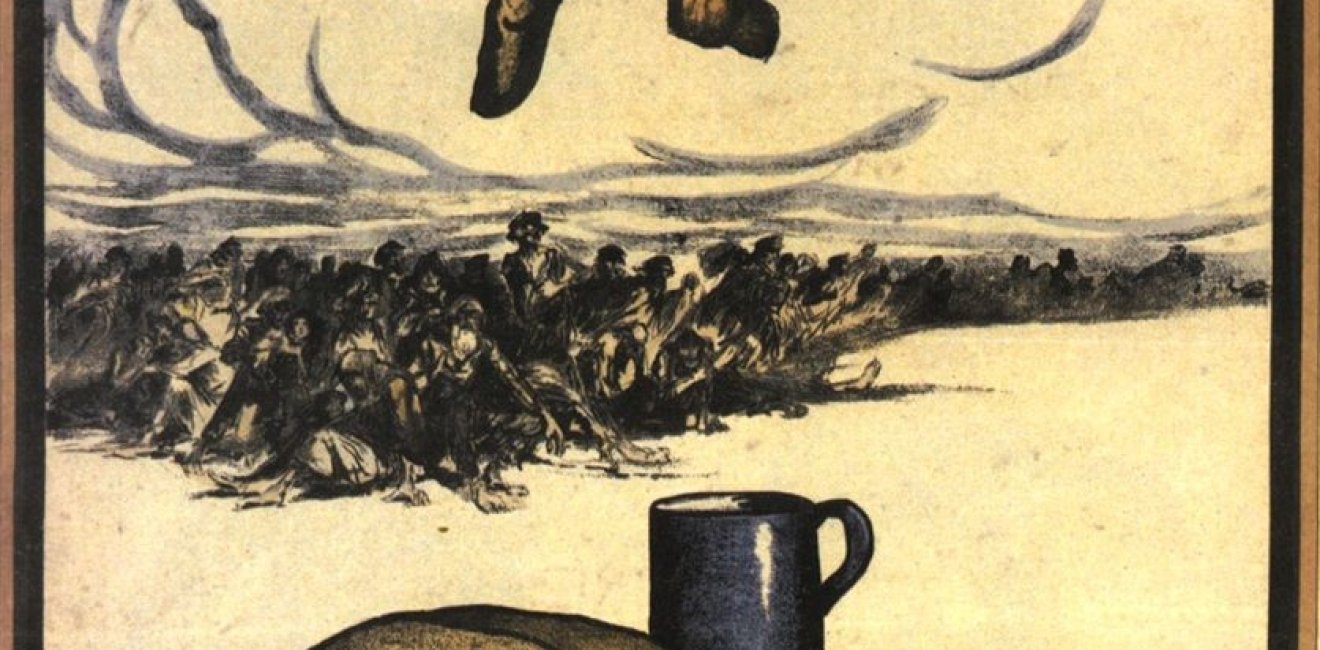

In March 1921, after three years of civil war, a terrible famine struck Russia. The Bolshevik policy of appropriating food surpluses (prodrazvyorstka), a wartime measure carried to an extreme, was largely to blame. The policy was robbing peasant farms, the engine of Russia’s agricultural economy, of any incentive to produce.

The American Relief Administration, a charity chartered by the U.S. Congress to provide food supplies to war-torn Europe, came to Moscow’s aid in 1921. Headed by the future U.S. President Herbert Hoover, it fed up to 11 million people daily at the peak of its operations in post-revolutionary Russia.

The Bolshevik government accepted foreign aid but was loath to become dependent on “greedy capitalists.” That is why the ideologically correct Workers International Relief (Internationale Arbeiter-Hilfe), based in Berlin, was created. The new agency was headed by Willi Münzenberg, a German communist and a close ally of Vladimir Lenin, who proved a PR genius. Willi Münzenberg’s name is not the most familiar one in the annals of twentieth-century propaganda but it deserves to be as well-known as that of Joseph Goebbels, Münzenberg’s Nazi counterpart.

For it was Münzenberg who, generously funded by the Soviet state, went on to stage all the early Soviet propaganda coups. It was he who masterminded the organizing of countless “antifascist,” “peace,” and “antiwar” committees. These committees, helmed by illustrious figures such as Herbert Wells and Albert Einstein and staffed by communist moles, produced countless pro-Bolshevik resolutions, complete with celebrity signatures.

Münzenberg largely deserves the credit for making left-wing politics fashionable among Western intellectuals and on university campuses. He worked to make “capitalism” and “fascism” sound morally equivalent. He was instrumental in organizing the League Against Imperialism, which first convened in 1927 in Brussels and initially counted among its supporters Chiang Kai-shek, the nationalist leader of China, and Jawaharlal Nehru, General Secretary of the Indian National Congress.

Münzenberg was also behind a mock trial that was organized in London in 1933 to counter the Nazi trial of a group of European communists accused of setting the Reichstag building, home of the German parliament, on fire. When the Nazis presented the fire as evidence of a communist plot against their newly established regime, Münzenberg responded by characterizing it as a Nazi false flag operation aimed at discrediting communists and the Soviet Union.

Münzenberg’s Workers International Relief, his first major operation, didn’t achieve much. It raised about $100,000, or about 1/600 of the amount raised by the American Relief Administration. It also insisted, suspiciously for an aid foundation, to be paid in money, not in kind. The cash Münzenberg laid his hands on served two purposes: it paid for his lavish lifestyle and his bloated operation, and it was used to portray the famine “as evidence of the diabolical designs of western capitalist governments to sabotage the Soviet regime by starving its citizens,” in the words of the historian Sean McMeekin.

In this as in almost all of his PR feats, Münzenberg was wildly successful. For a long time it was simply unfashionable among European intellectuals to attribute the Volga famine to anything other than the diabolical ways of the international bourgeoisie.

In 1939 Soviet Russia allied itself with Hitler, yet Münzenberg continued to portray it as the sole bulwark against Nazis. It engaged in genocide, purges, and mass murders, but most Western intellectuals turned a blind eye to these atrocities.

Münzenberg used bribes, manipulation, and flattery to cajole Western opinion leaders into acquiescing with Soviet politics. Anybody in the French or German artistic circles in the 1930s who dared raise the issue of Stalin’s gulags would receive the same cold shoulder as climate change deniers do today.

Russia’s modern propaganda efforts look pitiful in comparison.

Among the challenges Russia’s PR machine has to deal with today are the poisoning, in the British city of Salisbury, of the former Russian double agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter, and the use of chemical weapons by the Bashar al-Assad regime in Syria.

The results of Russia’s PR efforts in these matters are dismal, but not for lack of trying on the part of Moscow. Viktoria Skripal, a cousin of Yulia, Skripal’s daughter, first claimed that the poisoning was a private vendetta carried out against her relatives by a disgruntled future mother-in-law. Then Viktoria Skripal changed her story and turned to food poisoning. “Where’s the menu? What did they it eat at that restaurant?” she demanded to know. And then Russia’s UN representative, Vasilij Nebenzya, had a sudden revelation: the Skripals, he opined, were injected by Westerners with the Novichok nerve agent while unconscious in a sinister anti-Russian plot.

So was it a mother-in-law wielding a military-grade nerve agent or poor restaurant hygiene? Was it accidental food poisoning or an intended injection by Russia’s enemies?

Explanations for the chemical attack in the Syrian city of Douma were no less colorful. What they lacked in verisimilitude they made up for in the sheer scope of the possibilities offered. While the UN representative Nebenzya claimed there was no attack whatsoever and that all videos proffered in evidence were fakes, Maria Zakharova, Russian foreign ministry spokesperson, claimed that the separatists gassed themselves with smoke grenades produced in Salisbury, of all places.

It is in comparison with the Soviet-era propaganda machine, however, that the Russian propaganda of today looks weakest. It lacks a coercion mechanism at home and a base of supporters abroad.

No Russian will be sent to the gulag if she laughs at Nebenzya’s claims. No Russian will be arrested if he openly states that the Skripals were poisoned by the FSB. Yes, the state-run TV will threaten otherwise, but the major state-run TV news program, Vremya, is watched by 5 million viewers whose average age is 65, and the viewership is dwindling.

Only eight years ago, during the Russo-Georgian war, a Russian narrative that sought to portray the Georgians as the aggressors achieved some limited traction. Even after the annexation of Crimea some marginal political groups embraced Moscow’s narrative of a “fascist coup in Kyiv.” Today, few Westerners subscribe to the theory that the Skripals were poisoned by London in a smear campaign directed against Russia. Without an audience of believers, the Russian propaganda machine is yesterday’s sale item.

This is both telling and sad, because these latest Russian fake news items are not any wilder or more improbable than the Münzenberg Volga famine narrative. What makes propaganda is not so much its intrinsic qualities as the number of people willing to accept the narrative of the lie and the power of groupthink.

Russia currently lacks the means to impose its groupthink even on its own elite, let alone abroad. Moscow still has not found itself a Willi Münzenberg for the 21st century.

Author

Columnist, Ekho Moskvy; Columnist, Novaya Gazeta

Kennan Institute

The Kennan Institute is the premier US center for advanced research on Eurasia and the oldest and largest regional program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Explore More in The Russia File

Browse The Russia File

Chechnya as a Model of Modern Russia

Russia’s Indigenous Communities and the War in Ukraine

Gas and Power in a Changing US–Russia Relationship