A blog of the Kennan Institute

What Makes Ukraine’s Demography So Complex?

The Ukrainian demographic situation is an incredibly complex issue. Simply raising the population question requires that we first clarify our frame of reference. Are we asking about the Ukrainian population living within Ukraine’s internationally recognized borders, the so-called 1991 borders? Or about the Ukrainian population inhabiting the territory within the 1991 borders but without Crimea and Sevastopol (this is the area within which the State Statistics Service of Ukraine gathered information in 2015–2021)? Or about the population of both the territories controlled by the Ukrainian authorities before the start of the full-scale Russian aggression (the so-called 2022 borders) and the non-government-controlled lands? Or about the remaining population living on the territory controlled by the Ukrainian authorities after the start of the Russian full-scale invasion, and if so, in which month, since the current situation is highly unstable?

The questions become even more complex if we recall that all the data rely on information from the last census, which was conducted more than twenty years ago, on March 5, 2001. Since then, Ukraine has experienced a long process of large-scale internal and external migration, especially after the annexation of Crimea and the revolts in parts of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts in 2014. Even more people have been displaced since the beginning of Russia’s assault in February 2022. It is difficult to get reliable data on the population—namely, its size, composition, and movement—residing on government-controlled lands today. It is even harder to know what is going on with people in the occupied regions (parts of Kherson, Donetsk, Luhansk, and Zaporizhzhia oblasts).

To come up with answers, I will discuss the demographic situation using three frames of reference: Ukraine-1991 territories, Ukraine-2022 territories, and the lands currently under the control of the Ukrainian government. I fill in the information gaps with data-driven estimates from a selected number of reliable sources (these are listed in the notes at the end of the piece).

What We Can Glean from the Data

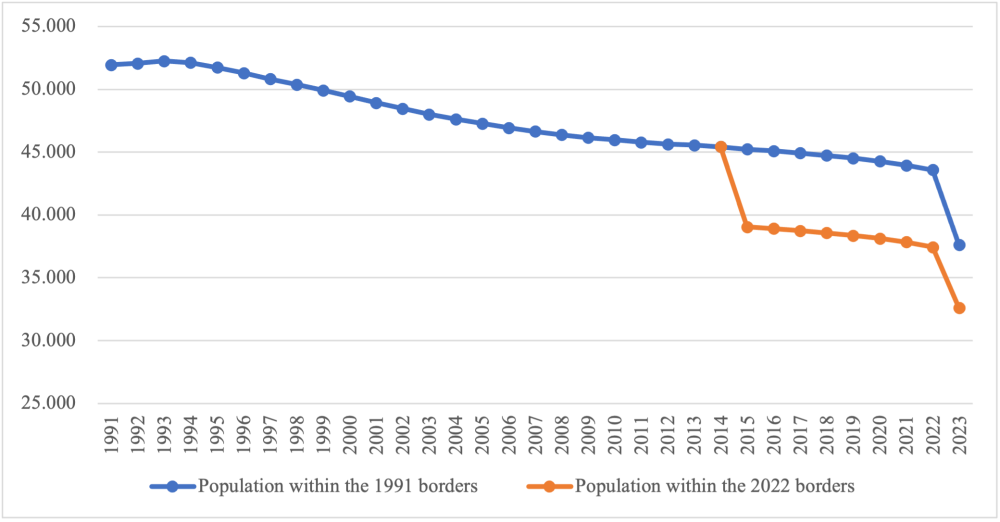

Since 1991, Ukraine has undergone a rapid process of depopulation, exacerbated by the large-scale departure of Ukrainians abroad, including labor migrants before the war and then those who have fled hostilities since 2014 (figure 1).

Figure 1. Size of the Ukrainian population (in thousand persons at the beginning of each year)

As of January 1, 2023, 37.6 million people lived in the territory within the 1991 borders, 32.6 million within the 2022 borders, and 31.1 million in the territories currently controlled by the Ukrainian government.

This means that the population losses within the 1991 borders exceed 14 million people (27.6 percent). This proportion increases to 37.4 percent if we add to the losses the population living in the non-government-controlled regions in 2014–21 (the loss would total approximately 19 million). The population loss within the 1991 borders increased by another 1.5 million after Russia launched its full-scale aggression (data as of January 1, 2023). Although part of the Russia-occupied territories was liberated, the population losses have probably increased in the last six months with the continued migration abroad, the constant shelling of cities, leading to concentrated civilian deaths, and the environmental disaster caused by the destruction of the Kakhovka dam.

Migration is the main engine driving Ukraine's demographic dynamics. Despite the apparently well-established system for registering border crossings, estimating the scale of the migration faces obvious discrepancies between Ukrainian and foreign data from the first days of the war. For example, according to the Ukrainian border service, between February 24, 2022, and May 24, 2023, 1.7 million more people left the country than entered. According to Eurostat (data as of April 30, 2023), almost 4 million Ukrainians who left Ukraine after February 24, 2022, were registered under the law on temporary protection in EU countries. Most of them are registered in Germany (1.1 million), Poland (1.0 million), and the Czech Republic (0.3 million). Approximately half of those who fled the war are women 20–64 years and one-third are children and adolescents.

According to a number of surveys of Ukrainians who have fled to Europe, 70 percent of the refugee women have higher (or incomplete higher) education; a significant number of the refugees have already found jobs, although only a third are working in their profession or using their qualifications; and the vast majority of children are receiving general or vocational education, indicating a good level of previous education.

Every month that Ukrainian refugees remain abroad reduces the likelihood of their return to Ukraine. On the one hand, they are working hard to adapt to living conditions in another country; on the other hand, the possibilities for a return to Ukraine decrease with the ongoing, targeted destruction of residences and critical infrastructure. The number of potential jobs in Ukraine is also declining. So refugees wanting to return to Ukraine might have nowhere to return to. The polls show that Ukrainian war refugees cite security, the availability of housing, and work opportunities as the main conditions for their return.

Forecasting Ukraine’s Demographic Situation

Despite all the risks that await them, I estimate that at least half the refugees will return to their homeland after the war. The experience of the Balkan countries suggests that about a third of those who fled the war could actually return home. The high level of Ukrainians’ patriotism, demonstrated by the return of 200,000 men from the developed countries to Ukraine in the first two weeks of the war, provides grounds for my more optimistic expectations of 50 percent coming back.

If Ukraine's economy is slow to revive after the war’s end, however, and if employment opportunities are unsatisfactory, Ukrainian families that are now divided, with men in Ukraine and women and children abroad, may choose to reunify abroad, not inside the country. This means Ukraine may lose an additional 1–1.5 million young, educated men.

It bears emphasizing that Ukraine is losing to migration not only the general population but people of a relatively young, reproductive age, educated and with work qualifications, usually determined to succeed, efficient and entrepreneurial. So the migration-related losses should be tallied not only in numbers but in the quality of the demographic resources lost to Ukraine.

Another important factor driving population loss is lower fertility rates. First the COVID-19 pandemic and then Russia's aggression caused a decline in Ukraine’s fertility rate, which was already the lowest in Europe. The total fertility rate (TFR) in 2021 was 1.2, and for 2022 it is expected to be 0.9. Since the births planned before the war were still delivered in 2022, a much more dramatic drop in fertility rate is expected in 2023: it will most probably achieve 0.7, and this level will remain at least until the end of the war. I see no reason to expect any compensatory effect in that regard, and the demographic dynamics will follow the models of what was seen after World Wars I and II. This means that after Ukraine’s victory, the TFR may return to the level of 1.3–1.4 only in the 2030s.

Irreversible human losses (i.e., deaths, including the direct losses of military and civilians due to hostilities and indirect losses caused by lack of timely medical care in the occupied territories, especially in the areas of active hostilities and shelling) have already had a significant impact on the average life expectancy (ALE) of Ukrainians. For 2023–24, the ALE will remain critically low: 70.9 years for women and 57.3 years for men. We can expect a return to prewar levels—76.4 and 66.4 years, respectively—no earlier than 2032, while the ALE of 77.8 and 67.7 years, respectively, will be back in Ukraine no earlier than the mid-2030s.

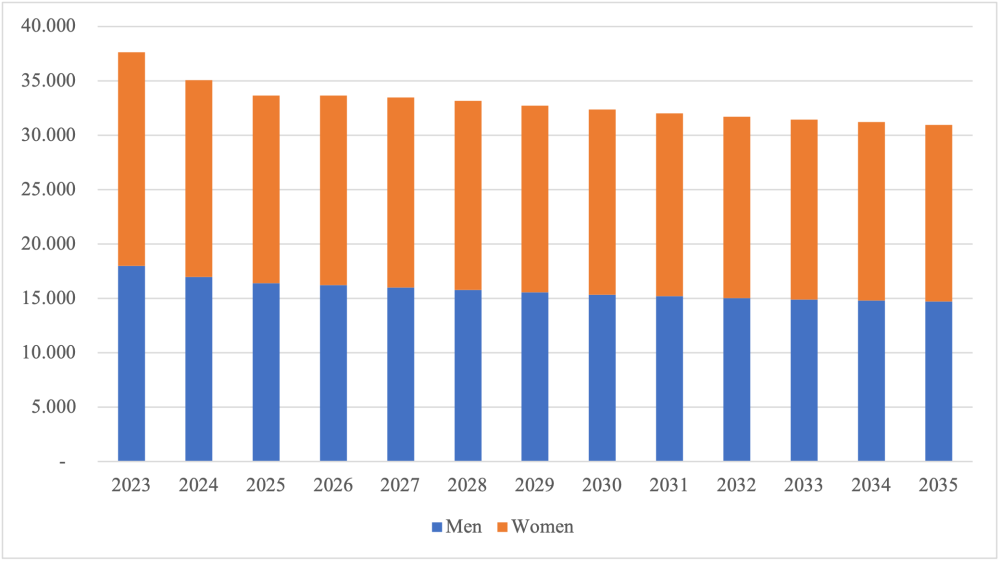

Thus, in a best-case scenario of the country's development—that is, a return to the 1991 borders and rapid economic and environmental recovery—further depopulation seems inevitable. Most probably by 2035, the population of Ukraine will have decreased by another 18 percent, falling from the current 37.6 million to 31 million (for the Ukraine-1991 territory). The demographic group of those aged 20–64 years old will decrease by 15 percent, falling from 23.7 million to 20.2 million, while the number of women of the most active reproductive age (i.e., 20–34 years old) will decrease by 11 percent, from 2.9 million to 2.6 million (see figure 2 for projected data).

Figure 2. Forecast of the Ukrainian population's size (within the borders of Ukraine-1991)

The opinions expressed in this article are those solely of the author and do not reflect the views of the Kennan Institute.

Notes

Sources of the data-driven estimates:

- The State Statistics Service on the number, sex and age composition of the population as of January 1, 2021, and January 1, 2022, and on births and deaths in 2020 and 2021.

- The State Statistics Service on the use of mobile communication services by households.

- Mobile operators (Kyivstar, Vodafon Ukraine, Lifecell) on the number of subscribers with the so-called main subscriber number.

- Rosstat on the population of Crimea, Sevastopol, and the occupied areas of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts.

- The State Border Guard Service on border crossings into Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, and Moldova or out of those countries into Ukraine (by day and month) as of February 24, 2022.

- Eurostat on the number of Ukrainians under temporary protection in EU countries.

- Rosstat on the number of Ukrainians who left for the territory of the Russian Federation and Belarus.

- eHealth system on birth rates.

- The Pension Fund of Ukraine on the number, age, and gender of contribution payers and recipients of social transfers (including pensions) during a certain period.

Author

Kennan Institute

After more than 50 years as a vital part of the Wilson Center legacy, the Kennan Institute has become an independent think tank. You can find the current website for the Kennan Institute at kennaninstitute.org. Please look for future announcements about partnership activities between the Wilson Center and the Kennan Institute at Wilson Center Press Room. The Kennan Institute is the premier US center for advanced research on Eurasia and the oldest and largest regional program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Explore More in Focus Ukraine

Browse Focus Ukraine

Talking to the Dead to Heal the Living

Ukrainian Issue in Polish Elections