A blog of the Kennan Institute

Writer Taras Prokhasko’s entire life and career have been shaped by Ukraine’s struggle for independence, from his days as a student protestor at Lviv University in 1989–91, through his award-winning career as a writer, to becoming an observer of life during wartime. On February 24, 2022, he began his story “War Begins Privately” by writing in the story’s first paragraph: “From this moment—the morning of 24 February—on, everyone will think that they are doing the right thing. People only do that which they can’t not do. It’s tempting to do what others are doing, but the desire to do things your own way is even stronger.”

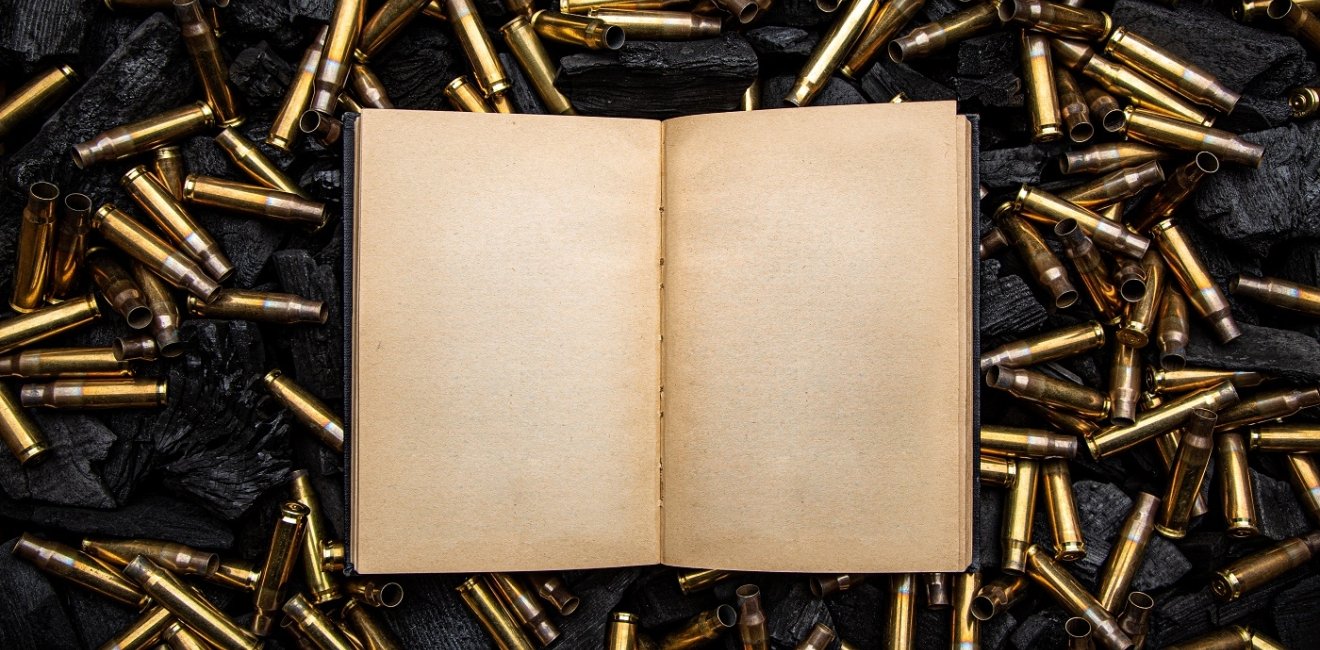

In a new collection of 28 essays, “doing things their own way” means writing, for Prokhasko and eight other prominent Ukrainian writers and cultural figures. Edited by Mark Andryczyk, a leading American specialist on Ukrainian literature, with translations by Andryczyk, Michael Naydan, and Alla Perminova, Ukraine 22: Ukrainian Writers Respond to War offers English-language readers a valuable opportunity to appreciate what has been happening inside Ukraine since the war began.

Together, the volume’s essays underscore the fact that the war began for Ukrainians in 2014, rather than 2022. They amplify the bitterness felt by many Ukrainians over the West’s unwillingness to acknowledge the threat to everyone posed by Russia ever after. They highlight the horror, rage, and confusion sparked by the full-scale invasion of 2022 in stories large and small.

Early in the volume, Yuri Andrukhovych, one of Ukraine’s best-known writers, recalls the warning he gave in Berlin at a 2009 celebration of the fall of that city’s wall dividing east from west. He broke an otherwise joyous and triumphalist atmosphere by reminding his Berlin audience that Moscow hardly embraced the “New Europe” it assumed to be free and fair. Russian aggression in Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine, he warned, regularly undermined any notion that the Cold War had ended. He ended by observing with a tinge of irony that “Europe is fated to become united. There is one certain generator of this: Russia.”

Sadly, his prediction has come to pass, as others in the volume—including Oleksandr Boichenko, Andriy Bondar, and Olena Stiazhenkina—elucidate further. A central question for Stiazhenkina is: how can anyone negotiate with criminals?

Other authors turn from the geopolitical to the minutia of life during wartime. The most powerful moments emerge when a gifted writer turns to the smallest detail of war: chats over a wine bottle being passed around in a city park; a four-year-old boy knocking on all his neighbors’ doors to insure that they hear the air raid siren; gathering in an apartment vestibule to sleep, in the hopes that it will be safter than the beds upstairs; pondering how many books will fit into a soldier’s backpack, and which one to take along to the front.

Russian brutality, from infamous Bucha to the unknown cottage community of Blyzhnni Sady, prompts questions about whether or not Russians have any shame; whether Russian culture can ever be separated from dreams of empire; and how Russia is so very unlike Ukraine. Prokhasko captures the differences he sees by recounting a train trip from Uzhhorod in western Ukraine to Moscow some time back: “The colorful flower gardens of Transcarpathia, the exquisite, lush order of Galicia, the green-colored flourishing of Greater Ukraine, the elaborate designers’ layout near Kyiv, the modest charm of near Slobozhanshchyna, traces of ethnic borders in the Bryansk region, the lapidary nature and monumental decay of the Moscow region. There were only grey houses behind board fences, bare yards without flowers and trees, only an outhouse and a pile of garbage in the corner.”

Such perceived differences flow through many of the essays in the volume, providing a sense of how differently Ukrainians and Russians view the world. Whether reading Andrukhovych’s account of the 1676 response to the Sultan of Constantinople, in which Kozaks famously told the Turks to go away, or Bondar’s declaration that “Russian culture has never been beyond politics,” the essays underline the great distance between Ukrainian and Russian world views.

Iryna Tsilyk reminds readers at the book’s close that the Russian invasion of 2022 is perhaps best understood in human—rather than political—terms. As she writes, “My phone suddenly vibrates—the air alarm is over; we can crawl back to our beds. The night ends, and with it the unbearable nightmares and waiting for dawn. Another night where I, holding the frightened child-deep-inside-of-me in my outstretched arms, swam out and didn’t drown. It’s time to make coffee and spin further, in a circle, in a circle, in a circle, like all people do.”

The opinions expressed in this article are those solely of the author and do not reflect the views of the Kennan Institute

Author

Former Wilson Center Vice President for Programs (2014-2017); Director of the Comparative Urban Studies Program/Urban Sustainability Laboratory (1992-2017); Director of the Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies (1989-2012) and Director of the Program on Global Sustainability and Resilience (2012-2014)

Kennan Institute

The Kennan Institute is the premier US center for advanced research on Eurasia and the oldest and largest regional program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Explore More in Focus Ukraine

Browse Focus Ukraine

Talking to the Dead to Heal the Living

Ukrainian Issue in Polish Elections