A blog of the Africa Program

What is religious about the conflict in Central African Republic?

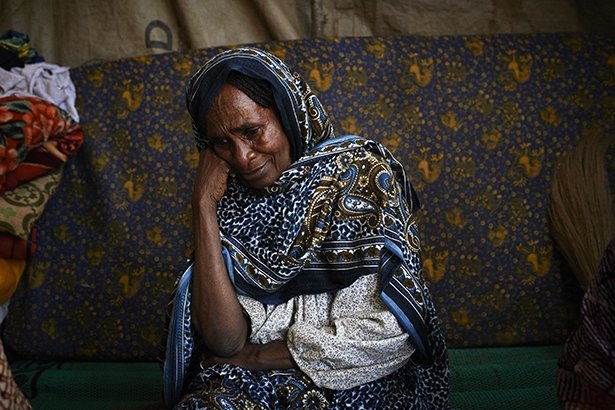

In the past two months, thousands of Muslims have fled or been displaced from the southern region of the Central African Republic, fearing for their lives in what some voices have warned might turned into a genocide. One of the episodes of this dramatic and unfortunate situation took place on April 27, 2014, as The Guardian reports, "Heavily armed African and French peacekeepers escorted some of the last remaining Muslims out of Central African Republic's volatile capital…bringing out more than 1,300 people who for months had been trapped in their neighbourhood by violent Christian militants." The ongoing violence between Seleka[1] and the Anti-Balaka[2] factions in Central African Republic has been extensively and persistently described as interreligious. The first has been associated with Islam and the second with Christianity, leading to the portrayal of the conflict as opposing Muslims to Christians. This sweeping characterization has to be taken with some caution. Indeed, Furseth and Repstad posit, "In debates over the role of religion in religious conflicts, there is often a tendency to either underestimate religion and reduce all religious conflicts to societal conflicts or overestimate religion and treat it as the dominant cause of the conflict." For the case of Central African Republic, I argue that the role of religion should not be overestimated in a conflict that is essentially political.

The Seleka saga

The Central African Republic has a population of about five millions inhabitants with an estimate of 80% Christians and 20% Muslims. The population both in the south and the north is extremely poor with at least 85% living below the poverty line, and the northern region experiencing greater poverty than the south.

Seleka appeared on the political scene in the Central African Republic in 2012 as a loose coalition of several dissident political and rebel groups. The rebel groups forming Seleka originated mainly from the marginalized northern part of the country, which is predominantly Muslim. They were without any clear political agenda, except their common objective and effort to overthrow the then head of state François Bozizé. They finally succeeded in forcing him out of power in March 2013 and their leader Michel Djotodia took over as the new ruler of the country. As this was the first time the country was being ruled by a Muslim since gaining independence in 1960, some of Seleka's members saw it as an opportunity to give a religious touch to their political agenda. Most of the combatants who overthrew Bozizé's regime were Muslims and a good number of Seleka members consistently exhibited intolerant behavior by explicitly targeting Christians and their properties in multiple acts of violence and extortion.

As Roland Marchal, a Political scientist and researcher at Ceri-Sciences-Po in Paris rightly puts it, "These armed movements, until [they formed a coalition were] more rivals than allies, recruit in the North of the country and beyond the borders, among cross-border ethnic groups. In these regions, the presence of the state is marginal, and the national sentiment is low, since the nationality of the inhabitants is often doubted, even among those born in Central African Republic." Marchal further suggests that Seleka's cross-border recruitments (mainly from Chad and Sudan) probably benefited the most from the tacit support of the Chadian president, Idriss Deby, who can boast of a military power in the region.

However, a few months after taking office as president, Michel Djotodia dissolved Seleka because of internal rivalries over power sharing. In the meantime, the group had grown unpopular in many southern cities for racketing and terrorizing Christian civilians, and Djotodia had lost control over the dismembered coalition. This turn of events has of course progressively exacerbated tensions between Muslims and Christians in the Central African Republic where they had so far peacefully coexisted.

The anti-balaka reaction

The anti-balaka faction, on the other hand, is also a loosely structured set of self-defense groups, which appeared on social scene in 2009 to counter the unbearable exactions and insecurity generated by organized armed robbery on the roads. At this initial stage, it had not political nor religion connotation. They simply embodied a limited community response to a situation of insecurity that the weak state apparatus was unable to address effectively. People felt they had to take responsibility for their own security. It is obvious that groups such as anti-balaka become uncontrollable once they emerged in a context of weak and unstable state such as that of the Central African Republic and are liable to recuperation and manipulation by political leaders.

Following the coup d'état by the Seleka rebels in 2013 and their inability to control and contain their extremist elements who where targeting Christians, the anti-balaka emerged once again as a grassroots response to an unbearable situation of terror which was destroying lives and properties. The rise of anti-balaka, coupled with the dismantling of the Seleka and the subsequent intervention of French troops, made the Muslims of the Central African Republic more than vulnerable. They became the main targets of acts of revenge by anti-balaka, accused of being accomplices of the crimes of Seleka members who were retreating from Bangui, which the French and African troops were struggling to stabilize. Since then, anti-balaka groups have been terrorizing Muslim communities they suspect had cooperated with the now-dismantled Seleka. Some have fled to neighboring countries and others have migrated to other parts of the countries were they feel more secure.

Political misuse of religion

The fact that Seleka members are mostly Muslims and that the reacting anti-balaka are mostly Christians has given a religious connotation to a conflict, which at its initial stage, was mainly political. Having acknowledged the religious twist of the conflict, it is important to underline the fact that neither Seleka nor anti-balaka both in their origins and nature qualifies as a religious group from a sociological point of view. Neither of these groups is institutionally directly related to a major religious organization nor is either pursuing a clear religious agenda, as is often the case with fundamentalist religious organizations such as Al-Qaeda, Boko Haram or al-Shebaab. Also, neither Seleka nor anti-balaka has the open support of any major religious group inside or outside of the Central African Republic. It is also helpful to bear in mind that neither Christianity nor Islam is a monolithic reality in this country where both religions, as elsewhere, have their own share of internal plurality and conflicts. It is just as difficult to link Seleka with a particular Muslim group as it is to connect anti-balaka with a particular Christian denomination. It is even suspected that some sections of anti-balaka are now controlled and manipulated by allies of the overthrown president, François Bozizé, for political purposes.

Nevertheless, it is difficult to know what were the real intentions of Seleka with regard to the religious component of their short political adventure in the Central African Republic. Some analysts have argued that Seleka was infiltrated by fundamentalist elements from neighboring countries that saw their political exploit as an opportunity to implement a fundamentalist religious agenda. If it is the case, it was surely a counterproductive political strategy to attempt to set Muslims against Christians in a country with such a strong Christian majority. However, now it will take decades to rebuild trust between these communities. In order to do so, it is crucial to involve religious leaders in this process, as political solutions will not be enough.

Dr. Ludovic Lado is a Southern Voices African Research Scholar with the Africa Program at The Wilson Center, and Director of the Institute of Human Rights and Dignity at the Centre de Recherche et d'Action poir la Paix (CERAP) in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire.

Photo Credit: S. Phelps with UNHCR via Flickr in the album "Central African Republic: Torn Apart by Violence."

[1] Sango word for "coalition"; Sango is the other major language of Central African Republic besides French.

[2] Meaning "anti-machete" or "invincible" in Sango.

About the Author

Ludovic Lado

Director of Institute of Human Rights and Dignity, Center of Research and Action for Peace

Africa Program

The Africa Program works to address the most critical issues facing Africa and US-Africa relations, build mutually beneficial US-Africa relations, and enhance knowledge and understanding about Africa in the United States. The Program achieves its mission through in-depth research and analyses, public discussion, working groups, and briefings that bring together policymakers, practitioners, and subject matter experts to analyze and offer practical options for tackling key challenges in Africa and in US-Africa relations. Read more