Lebanon, home to the largest number of refugees per capita in the world, including 1.5 million Syrian refugees (including those who are unregistered this figure is likely closer to 2 million) in addition to the nearly 500,000 Palestinian refugees, faces an acute humanitarian crisis, exacerbated by the country’s economic collapse, political instability, and recent Israel-Hezbollah war that displaced more than a million people. Both the Syrian and Palestinian refugees in Lebanon face systemic restrictions on employment, education, movement, and property ownership, trapping many in cyclical dependency and vulnerability. In addition, Lebanon’s crumbled state of affairs have for long harbored ground for systematic discrimination against the refugee population.

“With the recent Israeli attacks in Lebanon, the same trauma I experienced in Syria came back,” explained Lana, adding how hard she tried to work on her own trauma while being strong for her children and elderly parents.

Lana recalls leaving her studies at Damascus University in 2013 after threats of detention by the Assad regime’s Internal Security Forces. She, as well as other classmates and friends, were targeted for sharing anti-regime posts on Facebook—a charge so simple, yet detrimental for Syrians under Assad’s ferocious police state.

“So many of my friends and classmates were arrested—with some still missing. I have friends in Sednaya prison, including one who disappeared right after our last meeting.” Lana’s voice trembled as she talked about her friend, a journalism student who just two days after his initial release from detention was arrested again by the security forces and taken to what many are calling “Assad’s slaughterhouse.” “He told me he’s going to his mother’s house, but on his way home, they took him. I was the last person to see him since.”

Charged with an exuberant joy since Assad’s fall last Sunday, Lana is counting the days until she can return home. “I want to leave tomorrow if I can, but I know we need some planning.” She explained as she underscored the enormous travails her family undertook to pay insiders in Syria in an effort to remove her name from the regime’s “security list.”

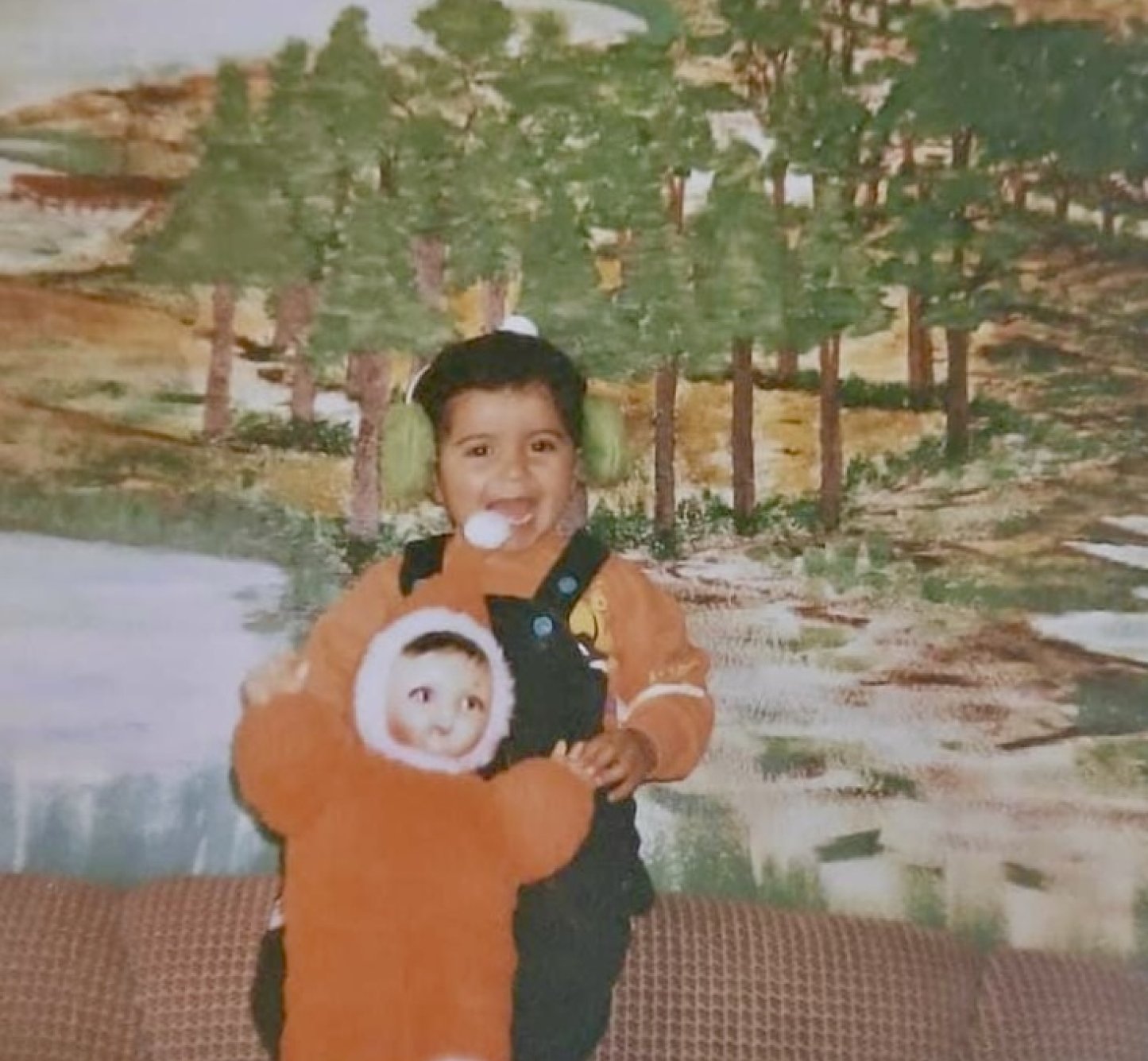

“I wasn’t successful. I’m still on that list,” said Lana. However, in the past few years, her now 6-year-old son Mohammad-Ali has visited the ruins of his mother’s home during his few visits to Zabadani with his father.

“I always wanted him to see my hometown, where I came from. Then the morning of Assad’s fall, when Mohammad-Ali found out that I can now go back, he turned to me and said, Mama let’s go home—let’s go.”

High on the promise of a new dawn for Syria, Lana shared her trust for HTS. “Assad did brutal things to his fellow Syrians; anyone other than Assad is better. I hope all Syrians would live in peace, and I think the free army will protect people. From my heart, I hope this. I believe this.”