Infrastructure is essential to addressing many of today’s core development challenges. It provides a foundation for social and economic security, ensuring that populations have access to vital public services and markets. It facilitates the transition to greener, more sustainable energy and transportation networks. And it even helps safeguard the free, open transmission of information vital to democracy.

The question is not whether to invest in infrastructure. Rather, it’s how to raise enough capital to meet surging demand. Across emerging markets and developing economies, the funding gap is expected to hit $10 trillion over the next decade. And that’s not counting the costs of rebuilding in today’s conflict zones. The price tag for Ukraine’s reconstruction is estimated at $500 billion, and it rises with each day of war.

Donor governments and multinational development banks (MDBs) are well aware of the problem and already dedicate large sums of money toward solving it. The G7’s assistance averages about $120 billion annually, and separate funds have been created for reconstruction efforts in Ukraine and elsewhere.

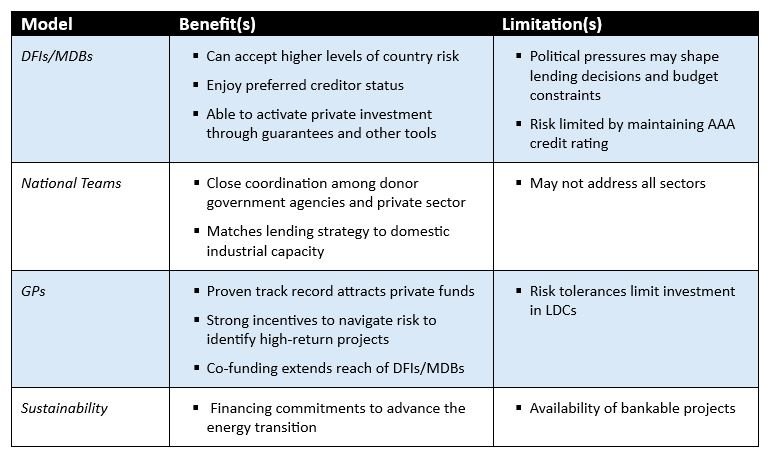

But state-led approaches are just one of several development finance strategies. There are four common models of infrastructure lending and investment, each with its benefits. Combined, they serve as cogs in a machine that produces modern, sustainable infrastructure.

DFI/MDB Model

Development finance institutions (DFIs) and MDBs are particularly important in the context of developing countries. There are significant swaths of the global landscape too tenuous for private capital to realistically invest in without significant derisking by public lenders. Even then, risks may deter private investors. Government-backed lenders are in a much better position to do the hard work of financing projects in the world’s least developed areas. DFIs/MDBs can better absorb risk because they are less beholden to market incentives guiding private investors, though MDBs must still protect strong credit ratings that enable the low borrowing costs that make their lending possible.

These government-backed lenders deploy a variety of tools that reduce risk to activate private investment. For example, the US International Development Finance Corporation offers political risk insurance and guarantees many of its products up to $1 billion. Multinational bodies, such as the International Finance Corporation, have set up local currency bonds and other hedging opportunity facilities to encourage participation in higher-risk projects. Efforts are underway seeking to activate greater private investment through co-investing or syndication, but they are still not fully realized.

“National Teams” Model

Donor governments vary in the extent to which they adopt a whole-of-government approach. Some countries effectively combine the expertise of their development bureaucracies, investment banks, and industry, creating a “national team” to pursue overseas projects. This approach may involve setting a master plan that guides the decisions of relevant agencies such as DFIs and export-import banks. It also involves fostering public-private partnerships where banks and investors lend in coordination with public entities.

The advantages of this approach are two-fold. It harnesses the knowledge and resources of the relevant agencies to pursue a coordinated, united strategy. And it can tailor projects to match the industrial strengths of the donor’s economy. Japan is one example. The Japan International Cooperation Agency devises master plans that focus on “development corridors” in specific countries and regions such as the Mekong Region, where Japan financed roads, rails, and ports in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Thailand. This Corridor development approach involves close coordination between government lenders, private lenders, and firms in the transportation sector, areas in which the Japanese economy has expertise and capacity.

General Partner (GP) Model

Infrastructure GPs have gained the trust of private investors and in doing so provide a vital source of capital, with the 100 largest firms raising more than $1 trillion in the past five years. GPs have earned the trust of investors by successfully identifying promising market opportunities and conducting the due diligence required to accurately assess risk and reward. GPs have the on-the-ground experience—along with the market incentives—to invest wisely by navigating risky environments to develop high-return projects.

As such, GPs can help mobilize capital from sources that might otherwise be deterred by informational barriers. Those sources include major institutional investors such as insurance companies and pension funds. DFIs and MDBs have found that co-funding with GPs allows them to reach more projects and more places than they could alone.

Sustainable Development Model

The final model is the array of funds established to help advance the energy transition. These include the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’s Green Climate Fund and many others.

Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs) came out of the Conference of Parties (COP) 26 in 2021, committing $8 billion to South Africa. JEPTs are designed to fund green energy infrastructure, reduce reliance on coal, as well as help transition communities and workers now producing coal and other fossil fuels. During the most recent COP, the United Arab Emirates took the lead in creating the ALTERRA Fund. These add to a dizzying array of funds seeking to apply resources to advance the energy transition, including Climate Investment Funds, GFANZ, Global Environment Facility, Green Climate Fund, and the International Partners Group. Deploying these funding commitments requires doing more to develop bankable projects.

Taken together, each of the predominate models of development finance has pros and cons. Rather than being viewed as substitutes, they must work in concert with one another. Only closer coordination among donor governments, MDBs, banks, and firms can generate the money needed to meet ongoing demand for capital. And this all has to be done with a commitment to high standards. That means there’s only one optimal strategy moving forward: more of everything.

Cosponsored by the Pacific Pension & Investment Institute

Authors

Associate Professor in the School of Government and Public Policy and the James E. Rogers College of Law, University of Arizona

Wahba Institute for Strategic Competition

The Wahba Institute for Strategic Competition works to shape conversations and inspire meaningful action to strengthen technology, trade, infrastructure, and energy as part of American economic and global leadership that benefits the nation and the world. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

De-risking Infrastructure Investment to Open the Door for Pension Funds

US Inaction Is Ceding the Global Nuclear Market to China and Russia