From Victimhood to Victory: The Evolution of the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall

Museums can be effective vehicles for displaying collective memory, or socially based reconstructions of the past that prioritize the needs of the present -over the veracity of the past and are frequently used by governments to promote nationalist agendas. Not only are public museums dependent on government funding, they also represent potent “sites of memory,” where memory ceases to be part of everyday experience and takes on a collective, physical form. Museums in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) are no exception.

Today, public museums in China are an important bellwether for gauging the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s legitimizing national narrative. Museums have attained such an important role in Chinese nationalism that, since 1982, they have been stipulated in successive versions of the People’s Republic of China (PRC)’s constitution as a type of “cultural undertaking” (wenhua shiye) of the state to “serve the people and socialism” (wei renmin fuwu, wei shehui zhuyi fuwu). The recent “museumification” of China has been well-documented – as of 2022, according to Chinese historian Xu Jian, there were 6,565 museums in China, and the number continues to grow.

In the 1994 Outline for the Implementation of Patriotic Education, the CCP made the connection between museums and national identity even more explicit. “Patriotic education bases” (aiguo zhuyi jiaoyu jidi) such as museums would be established to “cultivate patriotic sentiment among the youth” (ba peiyang guangda qingshaonian de aiguo zhuyi ganqing). Museums on the War of Resistance against Japan (China’s World War II) continue to prevail among patriotic education bases. As political scientist Wang Zheng notes in his 2012 book Never Forget National Humiliation, when the first 100 sites were designated as “patriotic education bases” in 1995, 20 percent were about the War of Resistance.

The most famous Chinese museum commemorating the War of Resistance is the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall. The site commemorates the Nanjing Massacre, the horrific six weeks from 1937 to 1938 during which the Japanese military slaughtered several hundred thousand Chinese non-combatants. The Memorial Hall was designed by Chinese architect Qi Kang and purposefully built around a mass gravesite excavated in the early 1980s, ensuring its powerful function as a “site of memory.” Skeletons of the victims remain half-buried in the ground beside placards that describe the methods of their demise. Initially opened on August 15, 1985, the Memorial Hall’s design, according to Qi’s 1999 memoir, was intended to reflect the themes of tragedy, disaster, and death.

Phase Two of the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall, which was completed on December 10, 1997 for the 60th anniversary of the Nanjing Massacre, included a new L-shaped entryway and several larger-than-life sculptures titled “A Disaster for Jinling (the ancient name for Nanjing).” Juxtaposed with Phase One, this phase focused more on the themes of current pain, hatred, and indignation, connecting the past to the present.

Emily Matson

Closer to present, Phase Three (built in 2007), the first phase not designed by Qi Kang, added an air of grandeur to the previous sentiments of solemn commemoration and fierce indignation. During its first two phases the Memorial Hall was barely visible from the street, but Phase Three added 20,000 square meters to the space, including a reflecting pool with sculptures of victims and an expanded hall with a dark “contemplation room” and a ceremonial courtyard to be used for events, such as the annual commemoration of the Massacre.

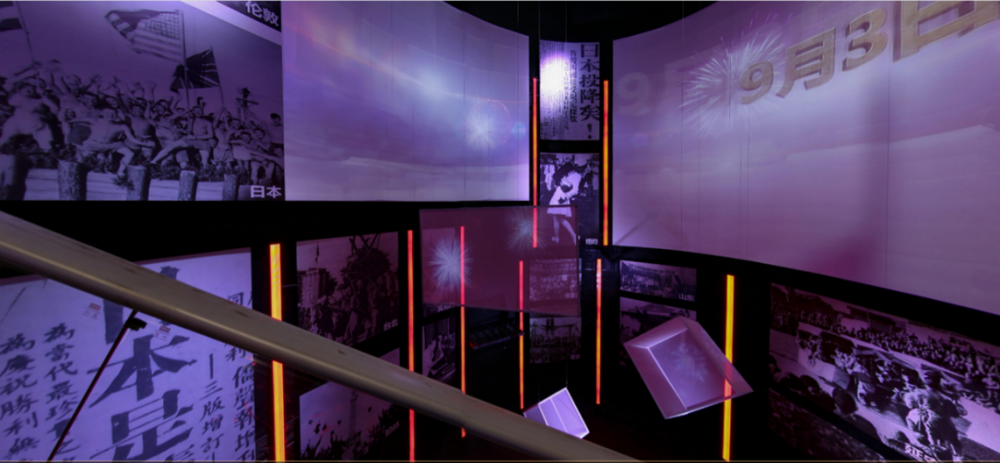

The fourth stage of the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall, the Victory Exhibition Hall, is the most recent and most aptly reflects the contemporary narrative of “national rejuvenation” under Xi Jinping. The Victory Exhibition Hall opened on December 7, 2015 and provides a comprehensive trajectory of the War of Resistance against Japan centered on the unconditional surrender of the Japanese Empire on September 2, 1945. In contrast with the earlier exhibits, the Victory Exhibition Hall appears designed to inspire pride in China’s victory. For example, the museumgoer is confronted at the entrance with the “Three Must Prevails” (san ge bisheng) text in multiple languages: “Righteousness will prevail, peace will prevail, and the people will prevail” (zhengyi bisheng, heping bishen, renmin bisheng). Upon entering the building, the grand entryway, with pictures of celebrations of the end of World War II taking place worldwide, sets a jubilant tone and places the Chinese victory against Japan in an international context.

Emily Matson

The phased development of the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall mirrors the evolution of the CCP’s legitimizing narrative, first from “victor” to “victim” and, under Xi Jinping, from “victim” to “rejuvenation.” In brief, during the Mao era, the “victor narrative” that dominated the CCP’s portrayal of the War of Resistance against Japan emphasized that, without the CCP’s ostensible defeat of Japan, there would be no new China. This narrative was largely based on Marxist class struggle. The “enemy” was both the Japanese and the Chinese bourgeoisie, which was epitomized by the Guomindang (GMD). Thus, portrayals of the heroic sacrifice made by Chinese Communists, but not the GMD and others, dominated the narrative in the Mao era. This was important domestically and on the international stage as a show of strength for a fledgling nation-state still contending for international recognition.

After the end of the Cultural Revolution and the death of Mao in 1976, however, the victor narrative gradually shifted to a victim narrative. Particularly in the early 1990s, trends and events such as economic marketization, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the Tiananmen Square Incident made it clear that Marxist ideology was defunct. The CCP needed a new legitimizing narrative, which came in the form of patriotic education centered on the Century of Humiliation and Chinese victimization therein.

The greatest outrage of the Century of Humiliation was the War of Resistance against Japan, and the atrocities Japan inflicted on Chinese civilians. For China’s leaders, fostering public outrage against past imperialist aggressors fomented patriotism and redirected outrage that might otherwise have been directed at the CCP for its crimes against its own people. This new victim narrative no longer vilified the GMD, and the PRC finally recognized patriotic GMD soldiers in the war effort.

We can still see the victim narrative clearly in the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall, particularly in Phase Two. However, with the museum’s Phase Four and the Victory Exhibition Hall, Xi Jinping has developed what I call the “rejuvenation narrative,” that incorporates elements of both the “victor narrative” and the “victim narrative.” CCP history has been drastically rewritten so that the Party’s historical mission is not to abolish the past but rather restore it. Instead of promoting a universal version of Marxism-Leninism, the CCP instead glorifies traditional Confucian culture and “socialism with Chinese characteristics.”

Under Xi, the Party stresses the heroic role of all patriotic Chinese in World War II as a way to legitimize the CCP both domestically and globally. Domestically, stressing the CCP’s leadership in World War II underscores the Party’s claim that “without the CCP, there would be no new China” (mei you Gongchandang, jiu mei you xin Zhongguo). Importantly, this narrative also highlights China’s presence at the creation of the post-World War II international order. However, the CCP’s version of this history is a bit of sleight of hand, as the lion’s share of China’s contribution to World War II, both in terms of soldiers and material resources, came from the GMD.

Xi’s motives for rewriting the history of the War of Resistance are not hard to guess. If, as Xi claims, the CCP comprised the “mainstay” (zhongliu dizhu) of the war effort against Japan, then it can also claim credit for ending the Century of Humiliation and Xi can justify his efforts to “make China great again.” As Xi remarked in his October 2017 speech to the 19th CCP National Congress:

With a history of more than 5,000 years, our nation created a splendid civilization, made remarkable contributions to mankind, and became one of the world’s greatest nations. But with the Opium War of 1840, China was plunged into the darkness of domestic turmoil and foreign aggression; its people, ravaged by war, saw their homeland torn apart and lived in poverty and despair…National rejuvenation has been the greatest dream of the Chinese people since modern times began. At its founding the Communist Party of China made realizing Communism its highest ideal and its ultimate goal and shouldered the historic mission of national rejuvenation.

Xi’s speech makes several assumptions regarding “national rejuvenation” (minzu fuxing) that need to be questioned. The first is that, because the CCP’s mission aligns with the “greatest dream of the Chinese people,” the CCP alone is historically the true representative of the Chinese people. Domestically, this makes it easier for the CCP to justify its continual crackdown on those who challenge the authority of the Party and its ongoing project of “cultural homogenization,” particularly in autonomous regions such as Tibet, Xinjiang, and Inner Mongolia.

The second assumption is that China should return to its rightful role as “one of the world’s greatest nations.” Again, Xi takes for granted that China and the party-state are one and the same. This claim has strong implications for the PRC’s imagined geobody and its contested territorial claims to Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the South China Sea. The resolution of all three of these claims is closely intertwined with Xi’s “China Dream” (Zhongguo meng), and their “losses” are still firmly linked to the Century of Humiliation. Hong Kong is linked to the First Opium War and subsequent British colonization and Taiwan to the 50 years of Japanese colonization and the subsequent retreat of the GMD to the island during the Chinese Civil War. Although the PRC’s territorial claims are matters of international importance, the CCP frames them as purely “domestic affairs” in which the outside world should not interfere.

Internationally, the CCP has grown more assertive as it pursues “national rejuvenation” under Xi. China’s infamous “wolf warrior diplomacy” features angry exchanges between Chinese diplomats and their foreign counterparts. According to Peter Martin, much of this posturing is related to China’s Century of Humiliation and the idea that Chinese diplomats should be proud of China and do not have to defend China’s way of doing things on the international stage. Although some analysts perceive a decline in “wolf warrior diplomacy” since the COVID-19 pandemic, aggression is still key to understanding China’s international behavior, particularly since there has been an increasing convergence between the bellicose tone of domestic and external propaganda (waixuan neixuan hua).

For the CCP, highlighting the Party’s role in World War II serves two seemingly contradictory purposes internationally. On the one hand, it can assuage the international community’s fears about China’s rise by characterizing China as peaceful. If China was a moral actor in World War II and helped create the international order post-1945, then surely we can trust it to uphold international norms today.

On the other hand, this same narrative allows the CCP to selectively deviate from the international order, because “national rejuvenation” demands China’s return to its historical leadership role. For example, Xi’s signature “Belt and Road” Initiative has extended from Asia and Europe to Africa and Latin America, reflecting China’s desire to expand its economic and political reach. Worryingly, China’s increased sphere of influence has facilitated its exportation of surveillance technologies to countries like Ecuador, Pakistan, and even Germany. Moreover, China is increasingly involved in efforts to promote pro-Beijing policies in democratic countries, particularly through targeting Chinese diaspora communities.

In sum, for the CCP, historical narratives in museums and elsewhere are often employed to reflect the Party’s current policy agendas (a strategy that is, of course, not unique to China). This uncomfortable reality should not diminish the very real horrors of the Nanjing Massacre and other atrocities of World War II. Rather, it should highlight that, in China and elsewhere, the most effective nationalist narratives are often based on kernels of historical truth. These kernels may be manipulated, but at their core they hold deep and real significance for the population. If we are to understand China today, we must therefore take seriously both the trauma of its history and how it is so often used to inform (and, at times, misinform) current attitudes towards the past.

The views expressed are the author's alone, and do not represent the views of the US Government or the Wilson Center. Copyright 2024, Kissinger Institute on China and the US. All rights reserved.

About the Author

Kissinger Institute on China and the United States

The Kissinger Institute works to ensure that China policy serves American long-term interests and is founded in understanding of historical and cultural factors in bilateral relations and in accurate assessment of the aspirations of China’s government and people. Read more