Kennan Cable 97: How to Engage Local Patronage Networks in Central Asia

Patronage has a negative connotation, suggesting corruption, inefficiency, and a detriment to the common welfare. International actors seeking to engage a developing country with aid typically attempt to avoid or to dismantle existing patronage networks, which are seen as harmful to their goals. But what if patronage networks actually benefit certain communities? In Central Asia, there are patrons acting as non-state power brokers filling gaps in social services and boosting local economies. While foreign aid typically focuses on increasing state capacities, many communities rely on such informal non-state networks to deliver vital tangible benefits. These patrons win community support through sustaining local economies while also acting as models of generosity and piety.

Development aid should engage with such networks and use them to build trust and encourage greater inclusivity and transparency, rather than dismiss them outright as corrupt actors. Local-level patronage differs from state-level grand corruption. If done properly, engaging with community networks has the potential to establish useful partnerships in advancing the goals of development.

State-Like Behavior from Central Asian Patronage

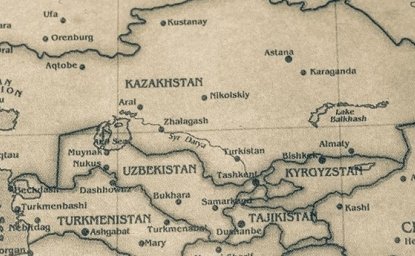

Patronage networks in Central Asia often step in where the state falls short, offering a wide range of services from jobs and infrastructure to education and healthcare. One of the most influential figures in this landscape was Kadyrjan Batyrov, a prominent ethnic Uzbek patron in Jalal-Abad, Kyrgyzstan during the 2000s. Batyrov, a successful businessman, built bazaars, shops, and an Uzbek Cultural Center by 2000. Then over the following decade, his projects played a major role in reshaping the city with a new university campus, school, newspaper, and medical clinic. He also fostered cultural landmarks, like building the region’s only Uzbek-language theater and restoring the city’s main Friday mosque.[1] Interviews with the city’s Uzbek population, which forms the majority of the city but a minority in the republic, indicated strong approval of Batyrov and his projects. They often cited specific ways their lives were improved: they worked in his enterprises, they shopped at his bazaars, they sent their daughter to his university, they published stories in his press, they benefited from the social networks that his establishments fostered. Most importantly, many said that Batyrov was fostering a genuine multi-ethnic community in a city with past interethnic conflict.[2]

These initiatives provided jobs, services, and a sense of ethnic pride among the long-marginalized Uzbek population. Batyrov carefully navigated the city’s political tensions between Kyrgyz and Uzbeks.[3] He maintained good relations with the city’s Kyrgyz leadership and then-President Kurmanbek Bakiev, positioning himself as a loyal citizen working for the benefit of all ethnicities.

However, Batyrov’s endeavors came to a sudden crash when political unrest shook Kyrgyzstan in 2010.[4] The “Second Kyrgyz Revolution” started with a power struggle in the capital, Bishkek, that ousted President Bakiev. The conflict soon spread across the republic and stoked latent Kyrgyz-Uzbek tensions in cities like Jalal-Abad. While Uzbeks perpetrated killings against Kyrgyz, Kyrgyz violence against Uzbeks was systematic and intense enough for outside observers to call events an anti-Uzbek “pogrom.”[5] Kyrgyz mobs targeted Batyrov’s institutions in Jalal-Abad, leaving them in smoldering ruins. His patronage network dismantled, Batyrov fled the country.[6] The tragedy of 2010, however, does not diminish the fact that for two decades, Batyrov built a stable, vibrant, local economy that provided material and social benefits to the city.

Another example of patronage filling state gaps comes from Andijan, Uzbekistan, in the early 2000s.[7] Akrom Yuldashev, an Uzbek businessman, led a group of religiously observant entrepreneurs who provided jobs, credit, skills training, and financial aid to local residents. Their network, known as "Akromiya," was rooted in Islamic principles of social justice, believing that business success should serve the greater good, analogous to citizen-organized business clubs like Rotary or Lions. The network gained substantial local support, evidenced by the large public rally supportive of Yuldashev’s circle that took place in Andijan’s central square before the 2005 Andijan Massacre.[8] Global and Uzbek media coverage of the government crackdown focused on the Uzbek government’s allegations that the Akromiya network presented a radical Islamic threat, and the government’s response to that alleged threat.[9] However, these accounts neglect that prior to the rally and its violent suppression, Yuldashev’s network had for years worked to address the city's socioeconomic needs. Perhaps the real threat Akromiya posed to the government was that their activities implicitly highlighted government shortcomings.[10] The state forcefully dismantled this patron network to eliminate a rival source of public provisioning, which had conferred an almost state-like legitimacy to Yuldashev’s network and helped to enable the city’s business environment to thrive.

When Patrons are Admired

Figures like Kadyrjan Batyrov and Akrom Yuldashev offer glimpses into homegrown solutions to Central Asia's chronic issues of economic underdevelopment and weak state capacity since the 1991 Soviet collapse, particularly in Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan.[11] These local patrons succeeded because they embodied communal values of mutual trust, obligation, and moral responsibility. Their constituencies admired them because they created jobs, built institutions, and seemed to live up to the image of ethical leaders giving back to their communities.

Research across Central Asia show that wealth is admired only if it is shared for the public good.[12] Rich neighbors who fund the construction of neighborhood mosques or infrastructure are respected, compared with many who only build lavish homes for themselves. Batyrov and Yuldashev harnessed these cultural values on a city-wide scale, presenting themselves as pious and generous benefactors. Central Asians are loyal to wealthy patrons who appear to practice communal responsibility motivated by religiosity.

Local patronage networks that provide economic and social resources for cities and villages are found across Central Asia. They are little studied, with only a few documented cases.[13] Those cases suggest that small-scale patronage arrangements generally tend to be stable and enduring.

Batyrov’s enterprises in Jalal-Abad came to a violent end for reasons external to his activities. The cause was the 2010 Kyrgyz revolution that started in the capital and spread to his city. Yuldashev’s business circle in Andijan triggered a violent national state response partly because he was too successful in providing economic benefits, and President Karimov of Uzbekistan was too insecure to allow public provisioning outside of his government. Although there are never any guarantees, other patrons have largely managed to stay clear of incurring the wrath or jealousy of authorities by cultivating mutually beneficial relations with the state, as Batyrov did before the overwhelming force of revolutionary change swept the entire republic.[14]

Limitations

There are limitations to patronage systems and risks for supporting them. Patronage is ultimately based on a shared moral framework of social solidarity and mutual help that binds patrons to constituencies.[15] The question is, what becomes of those who do not share in those values or are seen as living outside the bounds of communal standards? In my ethnographic studies of Central Asian neighborhoods, I found that the handicapped, divorcees, LGBTQ persons, Christian converts, and ethnic minorities are often excluded from the community’s social networks because they are seen as moral outsiders.[16] Such people have less access to shared resources and live more precariously. Patronage is premised on clear insider/outsider distinctions, because it is built on personal relations of mutual obligation that generally leaves others out.

Thus, one limitation is that patronage benefits those connected and tends to exclude others. Yet, Batyrov’s and Yuldashev’s legitimacy with constituencies was based partly on the broad distribution of benefits through institutions that they built (workplaces, schools, clinics, mosques), partly softening the exclusive effects of patronage.

Another limitation concerns efficiency and equity. Resources channeled through patronage flow mainly to those near the top of the hierarchy, leaving less for the wider community.[17] For example, at a macroeconomic level, the diversion of rents from Central Asian economies through large scale patronage into the personal offshore financial instruments of elites diminishes the fiscal options of each republic.[18] An extreme case is Gulnara Karimova, daughter of Uzbekistan’s ex-president, who stole hundreds of millions of dollars from the national coffers, contributing to the underdevelopment of her country.[19] Central Asian national elites are in that sense no different from other global elites who plunder national wealth and shelter those funds abroad.[20]

The same hazard can apply to state-level assistance, such as US aid intended to support economic reforms in Russia during the 1990s. One infamous example was the self-enrichment and corruption perpetrated principally by a network linking Harvard University academics and Russian economic officials led by Anatoly Chubais.[21]

Clearly, development aid that seeks to engage existing patronage arrangements needs to assiduously avoid those scenarios. However, one distinction to make is that, unlike the grand corruption of Karimova and Chubais, the cases of Kadyrov and Yuldashev concern patronage at the city level. The smaller scale of these networks can curb abuse, because some accountability results from face-to-face trust between patrons and their constituencies.

How Development Aid Can Engage Patronage While Mitigating Risk

Patronage is not an inevitable pathology of political economies. It is not an immutable aspect of "Central Asian culture." To move the region away from patronage’s limitations, development aid in the region can serve communities with a pragmatic, phased approach that can work with patron networks in the near term.

Aid projects could become more effective by recognizing that existing local patronage networks already provide material support, foster economic stability, and enjoy popular support. Instead of trying to dismantle these systems outright, aid efforts can work within them to gradually promote fairness, inclusivity, and transparency. Earning the confidence of community actors—state officials, business leaders, and informal authority figures—is key to this process.

The first step is to map existing patronage networks, identifying which arrangements are in place and who holds influence in a locality. This approach requires local research partners who understand the language, culture, and context to gather independent information. They would listen to people expressing their on-the-ground needs. What is patronage addressing well or failing to provide? An approach can then emerge to fill in the gaps.

Building trust with relevant state and non-state players is essential. An external aid project needs cooperation with state officials to gain permissions and operate effectively. Buy-in from entrepreneurs and informal leaders is also crucial, because these figures hold sway in the community.[22]

Projects should seek a beneficial outcome for all stakeholders and need to clearly communicate that goal. Thus, projects should be phased and monitored. Pilot projects enable development efforts to start small, offering to collaborate with patrons for a limited time, with mutually agreed conditions and metrics. Continuation of successive project phases would then be contingent on verified conformity to previous agreements.

One red flag would be if the material benefits flow inordinately (as specified by project metrics) to people like the patron’s allies or government officials. Project workers need to balance their core mission, the inclusive development of the community, with deeply ingrained expectations of elites to channel resources to their personal networks. Achieving this balance likely requires flexibility on all sides. Project workers should consider allowing some inequities in aid distribution for the short term, within tolerances specified internally by the project, to sustain engagement and influence toward long-term positive change.

Another red flag would be if the engagement created conflict between the project and locally influential players in the community, especially the patron himself. Those figures can view the foreign development agency as a rival power base, challenging their possible near-monopoly in community provisioning, undermining their authority with the constituency. National governments may also feel threatened, with the added insecurity that too much foreign aid may cast doubt internationally on a state’s sovereign independence.[23] Projects must approach influential state and non-state players in a sensitive manner that consciously avoids challenging their authority. The win-win nature of each partnership would be key to securing local buy-in.

A related red flag would be if the engagement causes conflict within the community. External resources flowing to a locality may result in disputes about who gets how much, provoking internal tensions. Part of monitoring involves remaining aware of the social effects of aid. Projects would then work with stakeholders to address these communal tensions collaboratively.

Red flags are not necessarily fatal to the project’s success. Some of them can be addressed directly according to problem-specific measures already mentioned. Some would need the project to evaluate the situation on the monitoring data, discuss them with the local partners, and possibly revise the conditions and metrics of engagement in a new trial period. If these measures fail seriously enough, the project would be terminated, and new sites of engagement sought.

As relationships deepen and trust builds, there is an opportunity to nudge patrons toward more equitable and transparent practices. By encouraging the inclusion of marginalized groups and promoting rules-based systems over personal connections, development aid can push these networks to evolve. The goal is not to upend local power structures overnight but to help them become more inclusive and fairer, ultimately serving the wider community more effectively.

Conclusion

Why engage with local patronage networks in this way? Effective external development aid can benefit communities broadly while still accounting for corruption. The examples of Batyrov, Yuldashev, and others suggest that the time has come to consider novel approaches to moving local communities toward more inclusive prosperity.[24]

Trust gives the development agency social capital (“street cred,” if you will) with which to nudge patronage arrangements to become more just and efficient. One can encourage the patron to extend his network of trust to cover more of the marginalized gradually. Over time, organic senses of community could begin to approach models of civil society where no one is supposed to be excluded.

These measures require local knowledge, vernacular languages, patience, and a willingness to work with imperfect arrangements (like patronage networks) in order to play the long game for transformation toward the kind of society Central Asians themselves want. They want broad opportunities and prosperity for all, regardless of who you happen to know.

This approach accords with a recent challenge by Charles King, professor of international affairs at Georgetown University, to base US modernization programs on better analyses of how things work on the ground. “How one thinks about the world determines how one acts in it,” he writes, because “in the absence of some broad understanding of what drives social and political change, the United States will continue to lurch from one crisis to the next.” In short: “being explicit about the way the world works is not an academic luxury.”[25]

More importantly, this form of engagement capitalizes on local actors that know actual needs and are already providing public services. It thus constitutes a superior alternative to the approach taken by China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) development projects. These projects are designed and implemented through consultations with national governments and often fail to consider or meet the population’s real needs. The BRI approach is susceptible to, and in fact can depend on, opportunities for graft involving the political elites of the recipient nation.[26] As a result, BRI projects often inflict recipient nations with crushing debt, eroded sovereignty, and citizen resentment.[27] A basic problem is that China emphasizes the “hardware” of physical development, while paying insufficient attention to the “software” of connecting with local institutions, ideas, and cultures.[28]

Connecting with local political economies and moral sensibilities is key to successful collaboration. Patronage is woven into how Central Asia operates but is mutable. Change towards more inclusion and transparency happens only by winning comprehensive local buy-in through patient, culture-sensitive engagement.

[1] Liu, Morgan Y. 2021. "Trust and informal power in Central Asia." Current History 120(828):262-67.

[2] Liu, Morgan Y. 2015. "Urban materiality and its stakes in southern Kyrgyzstan." Quaderni Storici 2015(2):385-408. My ethnic Kyrgyz informants in Jalal-Abad were less enthusiastic about Batyrov, but they also used the services his institutions provided, for example his university’s medical school enrolled many Kyrgyz students.

[3] Mateeva, Anna, Igor Savin, and Bahrom Faizullaev. 2012. "Kyrgyzstan: Tragedy in the South." Ethnopolitics Papers 2(Paper No. 17):1-40.

[4] Kyrgyzstan Inquiry Commission, and Kimmo Kiljunen. 2011. "Report of the Independent International Commission of inquiry into the events in southern Kyrgyzstan in June 2010." Pp. 88. Helsinki: Crisis Management Initiative.

[5]International Crisis Group. 2010. "The pogroms in Kyrgyzstan." in Asia Report. Bishkek and Brussels: International Crisis Group.

[6] RTE/RL Uzbek Service. 2018. "Fugitive Leader Of Kyrgyzstan's Ethnic Uzbek Community Dies In Ukraine At 62 " in Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty. Prague; Washington DC: Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty.

[7] Human Rights Watch. 2006. "The Andijan Massacre: One Year Later, Still No Justice." Pp. 10 in Human Rights Watch Briefing Paper. New York: Human Rights Watch.

[8] BBC News. 2005. "How the Andijan killings unfolded."

[9] Human Rights Watch, Rachel Denber, and Iain Levine. 2005. ""Bullets were falling like rain" : the Andijan massacre, May 13, 2005." Human Rights Watch / Helsinki Report 17(5(D)).

[10] Pomfret, Richard W. T. 2019. "The Central Asian economies in the twenty-first century : paving a new Silk Road." Princeton: Princeton University Press.

[11] Pomfret, op. cit..

[12] Liu, Morgan Y. 2012. Under Solomon's throne : Uzbek visions of renewal in Osh. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

[13] Some Central Asians claim such patronage networks pervade the region, but are unable to provide specifics of places and persons, according to my fieldwork. An original analysis of published Central Asian patronage cases is in Liu 2021, op.cit.. Ongoing, unpublished research by a local scholar in an Uzbek-majority city is also showing local patronage meeting economic needs, a network motivated by Islamic notions of societal justice.

[14] An excellent case study of a patron who built loyalty within his village and successfully curried favor with government authorities is “Rahim,” described in Ismailbekova, Aksana. 2017. Blood ties and the native son : poetics of patronage in Kyrgyzstan. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press.

[15] Urinboyev, Rustamjon. 2018. "Corruption in post-Soviet Uzbekistan." Pp. 1-8 in Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance, edited by Ali Farazmand: Springer International Publishing.

[16] Liu 2012, op.cit..

[17] Heidenheimer, Arnold J., and Michael Johnston. 2002. Political corruption : concepts & contexts. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers.

[18] Cooley, Alexander, and John Heathershaw. 2017. Dictators without borders : power and money in Central Asia. New Haven, London: Yale University Press.

[19] Freedom For Eurasia. 2023. "Who enabled the Uzbek princess?: Gulnara Karimova’s $240 million property empire."

[20] Burgis, Tom. 2020. Kleptopia : how dirty money is conquering the world. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers.

[21] Wedel, Janine R. 2000. "Tainted Transactions: Harvard, the Chubais Clan and Russia's Ruin." The National Interest (59):23-34.

[22] Liu, Morgan Y. 2024. "Trust and ‘corruption’ in Eurasia: toward an un-colonial approach." NewsNet: News of the Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies 64(3):10-14.

[23] Concerns about national sovereignty from too much aid have been raised about Kyrgyzstan. See Pétric, Boris-Mathieu. 2005. "Post-Soviet Kyrgyzstan or the birth of a globalized protectorate." Central Asian Survey 24(3):319-32.

[24] Again, Batyrov and Yuldashev are only two instances in a field of other Central Asian patronage cases, see Liu 2021, op.cit..

[25] King, Charles. 2023. "The Real Washington Consensus." Foreign Affairs 102(6):87-103, pp. 102-103.

[26] Lew, Jacob J., Gary Roughead, Jennifer Hillman, and David Sack. 2021. "China’s Belt and Road: Implications for the United States." Washington DC: Council on Foreign Relations.

[27] Miller, Tom. 2017. China's Asian dream : empire building along the new Silk Road. London: Zed Books.

[28] Callahan, William A. 2016. "China’s “Asia Dream”: The Belt Road Initiative and the new regional order." Asian Journal of Comparative Politics 1(3):226-43.

Author

Kennan Institute

The Kennan Institute is the premier US center for advanced research on Eurasia and the oldest and largest regional program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Kazakhstan in the Context of the War in Ukraine

The Future of Central Asian Water Diplomacy