Stamps, Rum, and Hand Grenades: Fidel Castro’s Recipe for Revolution

CWIHP e-Dossier No. 66

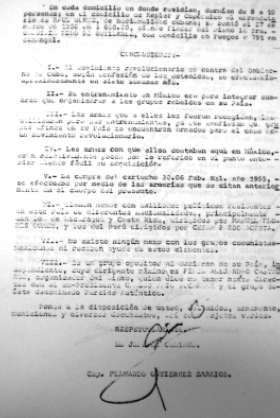

Source: Archivo General de la Nacion (AGN), DFS Galeria 1, Versión Pública de Fidel Castro, Leg. 1, Hoja 3-7. Obtained and translated by Renata Keller.

Stamps, Rum, and Hand Grenades: Fidel Castro’s Recipe for RevolutionRenata Keller[*]On 21 June 1956, Mexican intelligence agents watched as Fidel Castro and four fellow revolutionaries left their safe house in Mexico City and got into a green 1950 Packard. Discreetly, they followed the Packard through the streets of the city center. When Castro’s car pulled to a stop and three of its occupants got out, the agents descended. They seized the weapons that Castro and the other men were carrying and found more in the car, including a Czech rifle and almost a thousand bullets. The agents arrested Castro and his companions, launching an investigation that would nearly derail the Cuban Revolution.

Castro’s arrest report is an interesting document, to say the least. Its pages contain a sort of recipe for revolution, revealing the careful preparations that Castro and his companions undertook, as well as the supplies that they required. The report also offers insight into Castro’s character and the lengths to which he and his followers were willing to go to liberate Cuba.

In his interrogation, Castro confessed to the Mexican authorities that he had formed a group called the “26th of July” movement after the date of their previous failed assault on the Moncada Barracks. He told them that he planned to overthrow the government of Fulgencio Batista within six or seven weeks, boasting that this ambitious timetable was possible because the revolutionaries enjoyed the support of ninety percent of the Cuban population. Castro’s group planned to invade the island and lead the masses in an uprising against Batista. He explained that his supplies in Mexico were limited because they didn’t need to bring weapons to Cuba, just trained leaders.

He told them that he planned to overthrow the government of Fulgencio Batista within six or seven weeks, boasting that this ambitious timetable was possible because the revolutionaries enjoyed the support of ninety percent of the Cuban population.

These leaders that Castro was training had to learn a wide range of skills. For three months before their arrest, they had spent many of their days at a ranch just outside Mexico City, practicing shooting, demolition, camping, typography, and guerrilla warfare tactics. Castro told the Mexican officials that he himself supervised the training of his troops, with help from Spanish Civil War veteran Alberto Bayo Giraud.

The arrest report reveals just how meticulously Castro managed his followers. All forty members of the 26th of July movement had to turn their passports over to Castro for safekeeping. He kept track of how often each of them practiced, along with the number of cartridges they used, their levels of discipline and physical conditioning, and their leadership potential. Castro also had his followers fill out questionnaires in which they had to give their opinions about the other members of the movement. He compiled a strict list of house rules for all of his men, which included a midnight curfew, 8am wakeup, and small personal allowance of ten pesos per week. Castro controlled the finances of the entire movement, doling out the $400 monthly budget for weapons, clothing, food, medicine, writing paper, and postage stamps.

Castro confessed to his interrogators that the Mexican and Cuban postage stamps were actually the central part of an ingenuous secret code. He and his followers communicated with each other using stamps that, according to their classification and price, expressed various encoded warnings and instructions. Through this system, the revolutionaries could send messages such as: “We have spies” and “I am being very closely watched.”

Castro told Mexican officials that he also communicated with his followers using intermediaries and exile networks. One of the most important contributors to the effort was Hilda Gadea de Guevara, a Peruvian political exile and wife to Ernesto “Che” Guevara. Gadea received mail for Castro from his followers in Miami, Tampa, New York, Costa Rica, and Cuba. A Cuban woman, María Antonia González de Palomo, wife of the Mexican lucha libre wrestler Avelino Palomo, received mail on behalf of Castro’s group and let them stay in her house. Castro used his connections with Nicaraguan and Costa Rican exile networks to print propaganda for his movement in their countries. Another veteran of the Spanish Civil War, sculptor Victor Trapote, joined Castro’s 26th of July movement and served as a link to Spanish political exiles.

Castro painstakingly cultivated relations with groups within his host country as well. He confessed to the Mexican authorities that he had given written instructions to his men to establish friendships and other kinds of connections with various sectors within Mexico, including students, mail and telegraph workers, journalists, and political associations. Through these ties, Castro’s group gained “advantages” that they used in carrying out their training activities and preparations for revolution.

The Cuban revolutionaries had collected a small but varied arsenal, including pistols, rifles, axes, machetes, knives, hand grenades, fifty kilos of dynamite, and more than 3,000 bullets.

Getting ready for revolution required supplies, in addition to connections and training. When the Mexican authorities raided Castro’s safe houses and ranch, they found a wide range of weapons and other items. The Cuban revolutionaries had collected a small but varied arsenal, including pistols, rifles, axes, machetes, knives, hand grenades, fifty kilos of dynamite, and more than 3,000 bullets. Anticipating the need to set up improvised encampments, Castro’s group had acquired camping and construction supplies as well. Lanterns, binoculars, and backpacks joined a framing square and a carpenter’s brace on the list of confiscated items. The last item on the list was a 5-liter jug of Bacardi rum.

But Fidel Castro’s arrest report is also much more than a recipe for revolution: this document also helps explain the mystery of why Mexican authorities neglected to put a stop to the Cuban Revolution when they had the chance. It is worth noting that nowhere in the report is there any sense of alarm or danger. On the contrary, the author of the report, Captain Fernando Gutiérrez Barrios, repeatedly emphasized the limitations of Castro’s movement in terms of membership, funding, and arms. Gutiérrez Barrios also apparently believed Castro’s false claims that his group had no connections with former Cuban president and fellow exile leader Carlos Prío Socarrás. The report depicted Castro’s revolution as small, poorly supplied, and lacking in important political connections. Such a description made it easy to dismiss Fidel Castro and justified his release from prison. Based on the information in the report, Mexican authorities could reasonably conclude that they—and Fulgencio Batista—had more important things to worry about than Castro’s tiny group.

While it is impossible to know for certain why Mexican investigators took it easy on the Cuban revolutionaries, it is possible to hazard a few educated guesses. We know from later interviews with both men that Fidel Castro and Fernando Gutierrez Barrios struck up an unlikely friendship during their encounter. Perhaps the Mexican intelligence officer allowed his personal feelings to sway his professional decisions. We also know that Castro was a master manipulator. The report’s contents—and its absences—show that he was able to hide both his connections with Prío Socarrás (who actually was aiding the 26th of July movement and helped Castro purchase the Granma) and the fact that he was printing propaganda in Mexico with the aid of lucha libre wrestler and printmaker Arsacio Vanegas Arroyo. These important absences suggest that Castro’s confession, while extensive, was not as comprehensive as he led the Mexican authorities to believe.

On the whole, Fidel Castro’s arrest report is an extraordinarily revealing document. What would otherwise have been mundane details about supplies and daily routines take on greater significance in light of the subsequent success of the Cuban Revolution. The report illustrates the creative ways that Castro and his followers managed their limited resources. It demonstrates the importance of training, discipline, communication, discretion, and manipulation. Through this unique document, we can gain new insight not only into Castro’s operations, but also into the Mexican government’s failure to contain them.

[*] Renata Keller is Assistant Professor of International Relations in the Boston University Pardee School of Global Studies. She is the author of Mexico’s Cold War: Cuba, the United States, and the Legacy of the Mexican Revolution, available from Cambridge University Press.

Author

Cold War International History Project

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more

History and Public Policy Program

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more