In 2023, the University of Toronto Press published the fifth edition of Differences That Count, to which we contributed a chapter entitled “Together and Apart: Canada and the United States and the World Beyond.” Now that the cycle of Mar-a-Lago diplomacy has begun with the president-elect, it might be useful to step back and take a high-level (necessitated by the fact that we don’t yet know how everything is going to play out) look at which elements of that book chapter will change and what will continue. What many have long considered the status quo of Pax Americana had begun to unravel arguably even before the first Trump Administration, and next-door-neighbor Canada will have to not only strengthen its ground game) but also determine strategies for enhancing engagement with other key allies.

In terms of bilateral issues, the border catapulted to the top of the agenda well before the inauguration. As usual, the northern border is caught up in what are predominantly southern border issues. Immigration will continue to be top of mind, and the Government of Canada has moved quickly to announce enhanced border protection measures. A concern circulating in both policy and media circles is the prospect of refugee surges, particularly if the new Administration moves to implement mass deportations. With this in mind, policies such as the US-Canada Safe Third Country Agreement (especially the March 2023 amendment) could be in jeopardy.

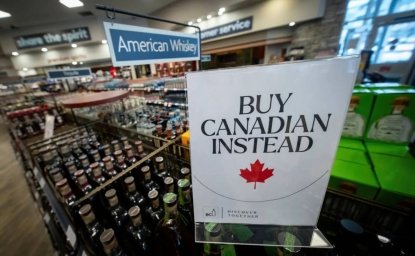

President-elect Trump’s announcement via social media of his intention to impose 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico has galvanized governments and media in Canada. There will no doubt be jockeying between provincial governments and various industries in terms of how Canada can be extricated from the 25% noose. Whether this is a or an empty threat, the prospect alone is a scary one. Unfortunately, the trilateral free trade agreement provides little comfort since Trump, even though he once touted it as the “best trade deal ever”, is unlikely to let US treaty obligations stand in the way of his self-congratulatory stance re the benefits of tariffs.

Apart from staving off tariff threats, and mitigating their impact if implemented, Canada will likely have to continue going its own way on trade agreements as the trajectories are different. The US withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement during the Obama Administration was a sign of things to come. At this point in time, there is no longer a significant domestic coalition for the expansion of US participation in trade agreements, and Canada will have to ensure that trade agreement partners are not using Canada as a backdoor to the US market (what Mexico is currently being accused of regarding Chinese goods). At the end of the day, US-China strategic competition will continue, and Canada will have its ongoing challenge of avoiding collateral damage. However, there are opportunities for bilateral collaboration vis-à-vis China, particularly in areas of Canada’s national interest such as AI and critical minerals.

What may present the greatest hurdle on the trade front will be the “review” of USMCA/CUSMA due to begin in 2026. Much will depend of course on how things play out beforehand, but the assumption is surely that the anti-trade headwinds will blow strong. It seems probable that the US will demand concessions (for example, on automotive rules-of-origin and on dairy access), either in the context of a renewed USMCA or outside the Agreement itself but as a condition of renewal.

Canada will once again be hosting the G7 in 2025. They will not want a replay of the ignominious end to its hosted Summit in Charlevoix, Quebec in 2018. Prime Minister Trudeau is currently the longest-serving G7 leader and there will be many new faces around the summit table in Kananaskis, all of whom will have their own challenges in dealing with the Trump Administration. The drafting of the joint communique may be reminiscent of the rodeo held every year in Calgary, not far from the summit location. Canada will be under pressure to produce a credible outcome, no doubt magnified by domestic political uncertainties and while by that time there may be some resolution to Ukraine, Gaza and other geopolitical sore points, Canada will be hoping to make contributions that will distract the US from the usual diatribes about defense spending—its recently announced Arctic foreign policy is a case in point.

On climate change, if the US threatens to abrogate obligations, Canada will once again face the existential question of whether to march in step, or stick with its commitments, thereby running the risk of losing competitiveness. But this seems to be the least of their worries. Depending on how the rest of the bilateral agenda evolves, there may be even more serious threats to Canada’s competitive position as a possible new Canadian government (with a different political complexion) emerging after the 2025 national election might prefer to mimic MAGA “pro-growth” policies, putting aside for the time being concerns about the globe’s steady warming.

The next four years will once again see a reduction of US government support of the UN system, a feature of the first Trump Administration. With public health facing many challenges, withdrawing (again) from the World Health Organization would magnify vulnerabilities, especially in the event of another global pandemic. The significant contributions of US-based philanthropic foundations may offset some of the losses and others (e.g., the UK. Germany) may again step up to protect what’s important.

The president-elect’s distrust of NATO was a feature of his first Administration. If whatever happens with regards Ukraine and Russia are considered a “win” by the second Trump Administration, that could perhaps lessen the pressure. However, clear divergence between the US, on the one hand, and Europe/Canada on the other, would make it difficult for Canada to sustain effective sanctions against Russian aggressors. To this end, NATO is no doubt preparing for the worst—actual US withdrawal -- and at the same time advocating against it. Abandonment of NATO by the US, or even ambiguity surrounding its commitment to Article 5 (collective defense) could necessitate Canadian reconsideration of its NATO Brigade leadership in Latvia. Apart from working to ensure that the United States maintains its commitment to continental defense through NORAD, Canada will likely move to cement ties with new NATO members Sweden and Finland, and work with them and other Arctic Council members to shore up northern defenses. The fact that Canada’s (pledged) augmented military spending likely will disproportionately be allocated to defense of the continent (with a notable focus on the Arctic) should increase scope for positive US-Canada NORAD cooperation.

On relations with other countries and the one which has the greatest potential for both disruption and collaboration, is both countries’ strategic competition with China. In the case of the US, it will continue to be on things like critical technologies and minerals, supporting China-competing firms, and preventing back-door entry of Chinese goods. Canada has little choice but to march in unison, but there will also be opportunity for collaboration on initiatives that will mitigate China’s market domination, for example, in EV batteries, critical minerals, renewable energy.

Overall, there are two principal trends identified in the chapter which will gather steam over the next four years. First, the dissatisfaction with trade liberalization, and the corollary reversion to selective industrial protections that will continue to fester under Trump 2.0. Much of what Canada was able to achieve historically with the Defense Production Sharing Agreement in 1959 will have to be replicated with the products and technologies of the 21st century in order for Canada to shore up its foothold in the US market and to have access to US government programs.

Second, what of Pax Americana? In the chapter we cited former Canadian Ambassador Alan Gotlieb quoting Lawrence Eagleburger who states that “unilateralism is the mood of the United States.” While Canada has traditionally taken a more multilateral approach, the US predilection has been to act based upon what is perceived to be in its interest, including consulting with allies. In the next four years we will likely witness the ongoing reluctance to commit US defense forces to conflicts and disturbances considered unworthy of involvement, or to support the structures of the liberal international order unless directly related to US interests. If Canada were inclined to up its investment in diplomatic capabilities, American First could create lots of opportunity for like-minded middle powers to cultivate deeper relationships with non-aligned developing countries unhappy with the demands they face from either of the two superpowers.

The chapter ends with a comment that both sides of the relationship tend to be more reactive than proactive, and that reverting to the status quo is the norm. However, maintaining that posture over the next four years will be challenging for Canada. An alternative might be necessary: one where Canada bolsters alliances with the like-minded on issues of mutual interest. The US will always be the predominant dance partner, but Canada, in its own self-interest, should pursue other partners for its dance card.

Authors

Distinguished Fellow, Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy, University of Toronto

Fellow, Balsillie School of International Affairs/Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Waterloo

Canada Institute

The mission of the Wilson Center's Canada Institute is to raise the level of knowledge of Canada in the United States, particularly within the Washington, DC policy community. Research projects, initiatives, podcasts, and publications cover contemporary Canada, US-Canadian relations, North American political economy, and Canada's global role as it intersects with US national interests. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Canada's 2025 Election: A Referendum on US-Canadian Relations

Mark Carney's First Week: Xavier Delgado on CBC