Review: Peter Navarro's ‘Crouching Tiger’

Former Financial Times bureau chief in Beijing and Washington and Kissinger Institute Fellow, Richard McGregor reviews 'Crouching Tiger', by Peter Navarro

Former Financial Times bureau chief in Beijing and Washington and Kissinger Institute Fellow, Richard McGregor reviews 'Crouching Tiger', by Peter Navarro

This review was originally published in the Financial Times.

At the core of Peter Navarro’s book is the conceit that this is a kind of geopolitical detective story, each chapter laying out clues for readers to assess the import of China’s rapid military development. The puzzle centres on a simple question: will the US go to war with China?

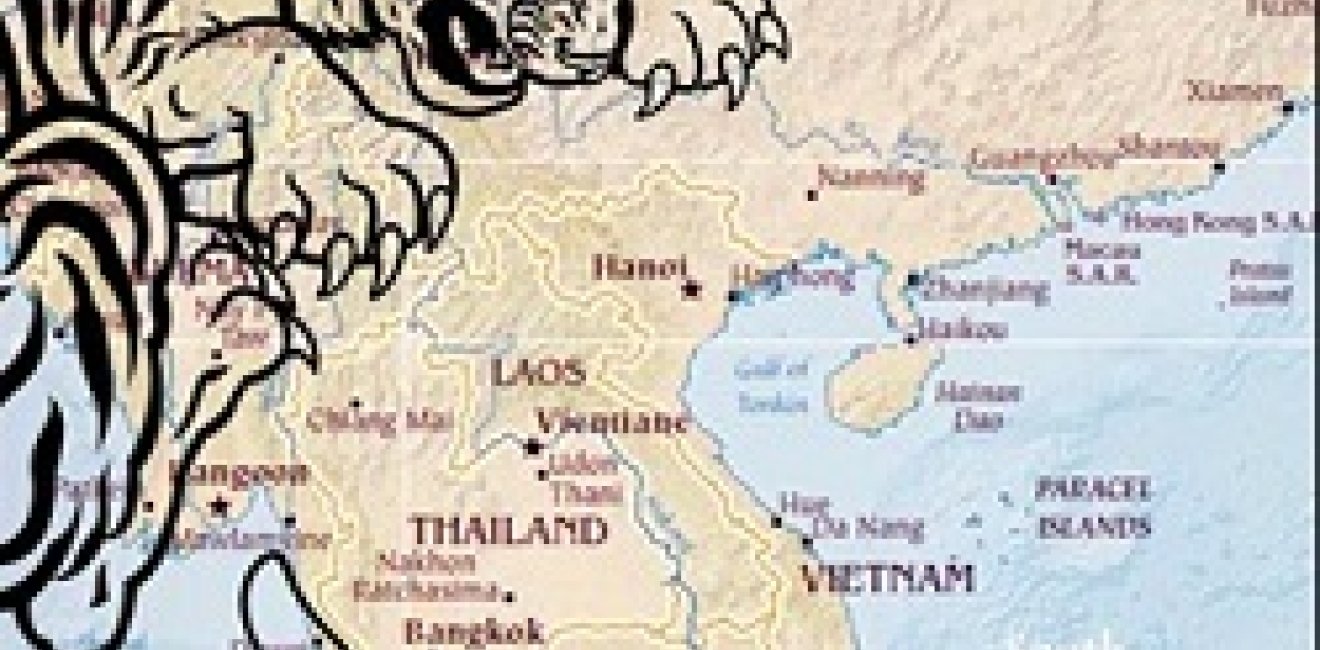

In truth, this is a detective story with little mystery. Navarro, a business professor at University of California-Irvine and long-time critic of China, does not so much lay out a trail of clues for readers about Beijing’s intentions as marshal the case for the prosecution from the outset. He harbours no doubts that China is a revisionist power that wants to neutralise the US in east Asia and supplant it as the regional hegemon.

This is hardly a difficult case to make. After all, China’s behaviour is what one would expect of any great power that wants to dominate its neighbourhood. That it is an aggrieved power with a chip on its shoulder from historic humiliations at the hands of the west and Japan, and has a political system that makes it an ideological rival with the US, only heightens the chances of conflict with Washington.

In that respect, Crouching Tiger is an extended riff on the utility of the “Thucydides trap”, the idea that an established power and an upstart rival will almost inevitably come into armed conflict. In Navarro’s telling, China is not so much drifting into this trap, but building a one-way super highway to reach it, eyes wide open, in readiness for conflict with America. He lays out the worst-case scenarios with clarity but adds little to the sum of knowledge about China’s military capabilities and strategic aims.

Navarro is not entirely to blame for the limits of his insight. China’s communist rulers have maintained, against the odds in an information-drenched era, a secretive system hostile to notions of transparency. As Kurt Campbell, a former state department official under US President Barack Obama, says in the book: “The US is all about showing what we’ve got. Look how powerful we are. You don’t want to screw with us.” China, by contrast, occasionally flexes its military muscles, and often claims not to have them at all — although that is a pretence even Beijing can barely manage these days given its recent island-building in the South China Sea.

Mostly, though, Beijing deflects attention from the build-up of its capabilities, either by attacking its critics or by refusing to acknowledge the military dimension to such activities. For China’s leadership, transparency is not a virtue but a weapon to be used against it.

As so often with books such as this, Crouching Tiger is as much about the US as about China. A grab-bag of familiar American failings, from creeping isolationism to the school system, are all cited. He also takes odd swipes at the “pervasive censorship” of Chinese news in western media, which makes one wonder whether he reads the newspapers he refers to in his footnotes.

Navarro’s book is part of a frustrating genre, of a call to arms against a menacing rival superpower that is invariably portrayed as acting out of the worst of motives. As an outsider looking in, the author has no fresh facts about China’s own internal debates and divisions, and fails to analyse both Beijing’s manifest weakness and its strengths.

Nor should any serious book about the US and China ignore, as Navarro largely does, the impact on Beijing’s behaviour of Washington’s own policies. More than 70 years after the end of the second world war, the US still has troops in Japan and South Korea; it conducts spying operations near China’s border; and has always made clear (if a little less stridently these days) that the country’s authoritarian political system is destined for the scrapheap of history.

America’s postwar Asian polices have undoubtedly underwritten the region’s economic success — but how would anyone expect China to react to a potentially hostile force on its doorstep?

The real question is what China wants in the place of the US-made postwar security system. At the moment, the leadership in Beijing either does not know or will not say, and Navarro’s book does not come close to solving the mystery.

The Kissinger Institute works to ensure that China policy serves American long-term interests and is founded in understanding of historical and cultural factors in bilateral relations and in accurate assessment of the aspirations of China’s government and people. Read more