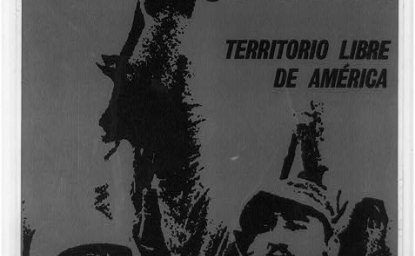

Castro’s endorsement of the Warsaw Pact's suppression of the Prague Spring in 1968 led to an incremental improvement in Cuba’s relations with the Soviet Union. Still, resolving differences between Cuba and the socialist states was a slow process that took over three years.

This process consisted of bursts of delegations and exchanges at expert and Party levels. During this visits, both sides sought to align their views, even as socialist diplomats had considerable criticisms of the Cuban leadership’s adventurous economic policies, which culminated with the risky and unrealistic sugarcane harvest plan of 1970. Such exchanges helped the East to understand that establishing closer trading cooperation with Cuba might help make that country’s economic development plans more pragmatic and predictable.

One of the most salient but contentious points in Cuba’s relations with the East in 1969, according to a Polish ciphered telegram, was Havana’s participation as an observer at the Communist and Workers’ Parties meeting in Moscow. In explaining the Cuban decision to participate in the conference, Carlos Rafael Rodríguez, the Cuban delegate, shared with the Polish ambassador in Havana Leonid Brezhnev's urgent plea for Fidel Castro to attend the gathering. To Moscow, the PCC’s participation at the conference was a key symbolic gesture placing Cuba on the Soviet side of the Sino-Soviet split, which was important given Havana’s formal non-involvement in this dispute.[1]

However, as we learn from another Polish diplomatic dispatch, Cuba’s attendance seemed insufficient to impress the Soviet Ambassador Soldatov, who expressed his regrets to Fidel Castro that the PCC could not fully participate in the conference at a crucial moment for the communist movement.[2]

Furthermore, in early 1969, problems between the East and Cuba continued not only at a diplomatic but also at a party level. Following the bitter January 1968 PCC Central Committee plenary meeting and the Soviet Bloc’s open disagreement with Cuba’s foreign policy in Latin America, Havana refrained from sending delegations to the East German and Polish party congresses in East Berlin and Warsaw, following the lackluster reception of the Cuban foreign policy positions at a Bulgarian congress in Sofia.

As it was customary for such party summits to be used to exchange views on international relations, the Cubans believed that their delegations should not attend the congresses only to deliver their greetings and not be able to explain their policy perspectives fully, a Cuban diplomat told his Polish counterpart.[3]

By 1969, the worsening state of the Cuban economy became the key factor in the relations between Cuba, the Soviet Union, and the East European states. For example, Bulgarian experts visiting Havana in August 1970 appeared unimpressed by Cuban obstinacy. In a report on their visit to Cuba, Sofia informed Budapest that the Cuban economy continued to lack real planning strategies. According to the Bulgarians, the essence of planning remained “very foggy” to the Cubans, although it figured in Cuban leaders’ narratives. The explanations of their actions were equally “vague” as they refused to accept the notion that it was impossible to build a new society without scientific planning.

A turning point in the Cuban economy came during the 1970 sugar harvest - the audacious attempt to produce a record-breaking 10 million tons of sugar, known as the Zafra de los diez millones (“the sugarcane harvest of the ten million [tons]”). The attempt mobilized the country’s full attention. Soviet Bloc representatives and guests were also involved in the massive undertaking. For example, the Bulgarian leader Zhivkov shared with his Czechoslovak counterpart that Sofia sent students to take part in the harvest.[4]

However, the zafra failed. Due to the 1969 drought, Cuba could harvest only 8.5 million tons of sugar in 1970, despite the colossal effort. The harvest, involving Cuba’s entire workforce, nearly wrecked the national economy, as all available resources were concentrated on the sugarcane harvest, seriously neglecting the service sectors and industry, essentially negating previous attempts at balancing agriculture with other sectors of the economy, as stated in a conversation between Cuban and Albanian officials.[5]

While the Cuban people behaved “like heroes” in this production battle, as Fidel Castro noted, the country’s leadership saw the missed zafra target as the revolution's first failure, Hungarian diplomats observed. Fidel even went as far as offering to resign, something the crowds in Havana vehemently rejected.[6]

The Bulgarians believed that in all areas of Cuban economic development, the socialist states had to extend additional help to stabilize the country and make it a showcase for socialism in Latin America. Sofia also stressed that the East European states should do everything possible to convince Havana that it was time to gradually align its perspective plans and integrate its economy with the socialist states. Therefore, in the Bulgarians’ view, the East European states needed to develop a comprehensive, long-term program to broaden their political, economic, and cultural relations with Cuba.[7]

Improvements in party relations were high on the agenda as well. At the PCC’s invitation, a Hungarian party and government delegation traveled to Havana for the national holiday on July 26, 1970. During the meetings, the interim organizational secretary of the PCC’s Central Committee, Major Jesus Montané Orpaesa, addressed the need to improve relations between the Cuban Communist Party and the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party. Eventually, based on the authorization of the Central Committee of the Hungarian Party, the delegation agreed to start sending party delegations each year to exchange experiences with its Cuban counterparts.[8]

Prague’s envoys also praised the Cuban withdrawal from its strategy of fomenting rebellion in the Western Hemisphere. The foreign intelligence resident at the Czechoslovak embassy, Major Ota Jiroušek, stated that the second half of 1971 was the most crucial period in normalizing Cuban relations with Latin America. He thought that while the Castro regime had experienced serious political and economic failures at the end of the 1960s, 1971 would be the year it began pursuing more realistic policies in all spheres. Likewise, the Czechoslovak intelligence representative in Cuba reported that many Latin American countries were considering the possibility of returning Cuba to the Commonwealth of Latin American States.[9]

The meaning of the winding process of rapprochement between Cuba and the East was well summarized by the Bulgarians, who in 1970 saw it as a chance for the East to help the Cubans acquire a broad understanding of the experience of the socialist state that would help guide them on their Leninist path of development.[10] The numerous exchanges of visits at expert and party levels between 1969 and 1972 helped bring Cuba and Eastern Europe closer together and allowed Havana to tackle acute issues in economic and regional policies. The fact that critical East European views gave way to growing praise reflected the positive direction of development in relations between the partners. This improvement climaxed with Fidel Castro’s month-long visit to the Socialist states in 1972 - which I will discuss in the next blog post and which proved crucial in Cuba’s embark on socialist “institutionalization,” helping bring about its “accommodation” with the East.

Connected Sources

Cipher No. 6247 from Havana

Note from the Conversation between the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Comrade Jędrychowski, and the Ambassador of the Republic of Cuba, Flores Ibarra

The Position of the Communist Party of Cuba Towards the Conference of the Communist Parties and the Problems of the International Revolutionary Movement

Letter, Political of the Central Committee of the Bulgarian Communist Party to the Central Committee of the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party

Protocol of the Conversations Between Comrade Todor Zhivkov - First Secretary of the Central Committee of the BKP and Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the PRB, and Comrade Gustav Husak - First Secretary of the Central Committee of the KSČ

Reception of the Party Delegation of the Cuba Government by the Prime Minister, on 28.11.1964

Foreign Affairs Department of the Central Committee of the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party, 'Report on the Party and Government Delegation’s Visit to Cuba'

Czechoslovak Embassy in Havana to Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 6th Territorial Department, 'Cuba-Latin America-USA Relations in the Second Half of 1971'

[1] Strzałkowski to Jeleń, Cipher No: 6247, 4 June 1969, AMSZ, D.VI-1969, 37/75, W1, p. 1.

[2] E. Noworyta, "Stanowisko KP Kuby wobec narady partii komunistycznych i problemom międzynarodowego ruchu rewolucyjnego" [The position of CP Cuba on the council of Communist parties and the problems of the international revolutionary movement, 3 September 1968, AMSZ, D.VI-1969, 36/75, W-2, p. 1.

[3] Notes on conversation, Stefan Jędrychowski [Polish Foreign Minister] - Flores Ibarra [Cuban Ambassador to Warsaw], 12 February 1969, AMSZ, D.VI-1969, 36/75, W2, pp. 2-3.

[4] Memcon, Todor Zhivkov - Gustáv Husák, 17 February 1970, TsDA, f. 1B, op. 60, a.e. 36, p. 31. The importance of the zafra and the participation of Eastern countries was well understood in Cuban criticism towards the Hungarians who failed to send a reed-cutting brigade to Cuba, which the local leaders perceived as an important expression of solidarity.

[5] On the attempts to balance the Cuban economy in the mid-1960s, see Memcon, Mehmet Shehu - Wilfredo Rodríguez, 28 November 1964, DPA, f. 14 , l. 5, d. 1, p. 5 [6].

[6] “Párt- és kormányküldöttségünk kubai útjáról /А küldöttség jelentése/” [On the trip of our party and government delegation to Cuba (Report of the delegation)], 9 September 1970, MNL, M-KS, 288f. 11/2964 ö.e, pp. 5-6 [7-8].

[7] [Information on BCP CC visit to Cuba], MNL, p. 9 [111].

[8] “Párt- és kormányküldöttségünk kubai útjáról /А küldöttség jelentése/,” p. 2 [4].

[9] Ota Jiroušek, "Ke vztahům Kuba - Latinská Amerika - USA v druhé polovině r. 1971" [On relations Cuba - Latin America - USA in the second half of 1971], 28 January 1972, NAČR, KSČ-ÚV 1945-1989, Praha - Gustáv Husák, k. 379, p. 1.

[10] [Information on BCP CC visit to Cuba], p. 8 [110].