A blog of the Wilson Center

Claudia Sheinbaum made history by being elected as Mexico’s first female president. But just hours later and 300 miles from the capitol, the assassination of a small-town female mayor also made history.

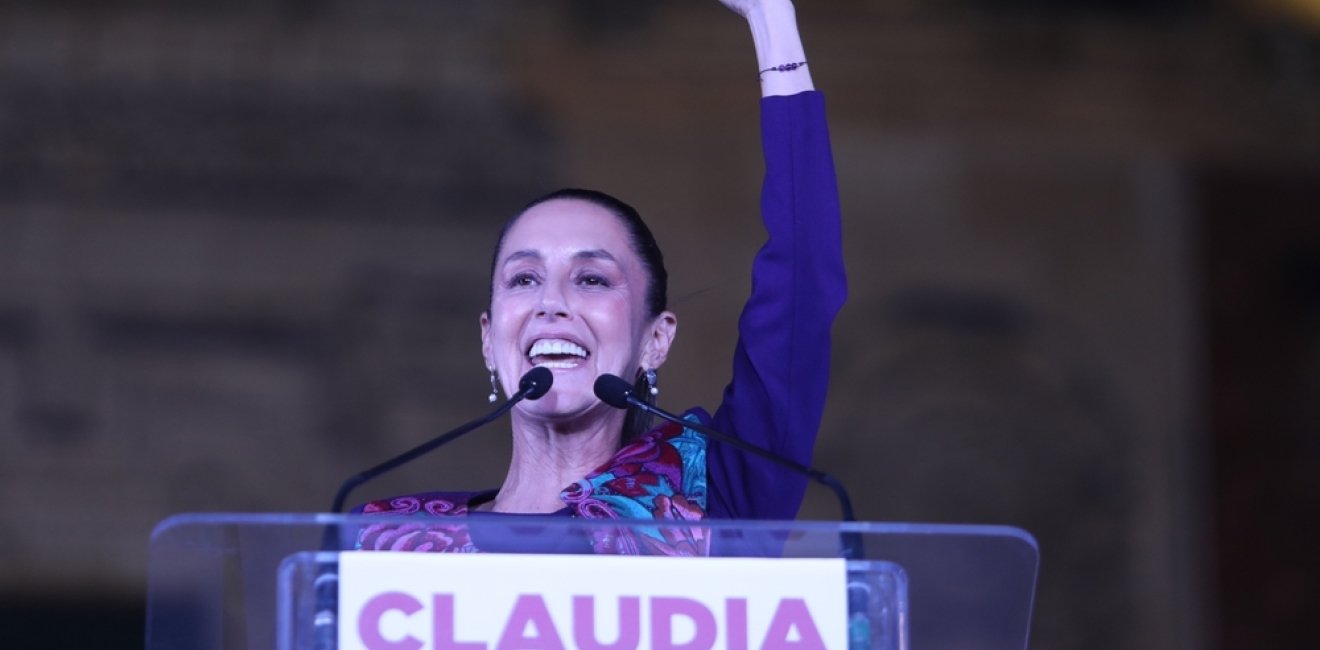

Claudia Sheinbaum’s June 2nd election broke new ground for Mexico. On October 1st, she will become the country’s first woman president, nearly six years after taking office as Mexico City’s first female mayor. Receiving close to 60% of the vote, her 30-point margin of victory was the largest since 1982, when Mexico was still under one party rule. With Sheinbaum at the top of the ticket, the Morena Party captured 7 of 9 governorships, and more than 250 of Mexico’s 300 directly elected congressional seats.

Mexico’s 2024 elections saw history being made in other ways, too, both tragic and disturbing.

Hours after Sheinbaum declared victory, Yolanda Sánchez—the first female mayor of Cotija, a small city west of the capital—was shot 19 times as she walked home from the gym. Her assassination, which many observers believe was the work of the Jalisco New Generation drug cartel, wasn’t a complete surprise. Since she took office in 2021, organized criminal groups seemed to have Sanchez in their sights, and in 2023 she was kidnapped and terrorized by her captors for three days.

While this election cycle has probably been the most vibrant in Mexico’s modern history, it has also been its most violent. At least 37 people seeking office were killed (some estimates put the number higher), and more than 828 non-lethal attacks were recorded. Left unchecked, these attacks threaten to undermine democracy itself. For example, after two candidates for mayor in Michoacán were killed on the same day, 10 candidates in other local races withdrew their candidacies out of fear.

It’s not only candidates and office holders who have been victimized: family members of candidates have also suffered. At least 14 relatives of candidates were killed in recent months.

Gangs and drug cartels are often the culprits in politically motivated violence, especially when it comes to local elections, because that’s where politicians can best protect—or ignore—their interests. A recent investigation by the New York Times found that organized crime groups were involved in at least 28 of the 36 candidates killed this campaign season. While Mexico’s national government pledged to protect politicians as they campaigned this year, and deployed security forces to defend 487 candidates, state governments lacked the resources to assist in these efforts and protect local politicians from political extortion and cartel violence—politicians like Cotija’s Yolanda Sánchez.

For female politicians in Mexico, the challenges run even deeper. While more women ran for office than during any other election cycle in Mexico’s history, women overall in the country have suffered under record-breaking rates of gender-based violence and femicide. According to a Mexican government survey, more than 70% of women and girls over the age of 15 have experienced some kind of violence throughout their lives. Sadly, this trend has also been felt elsewhere in the Americas. The Wilson Center’s Latin America Program recently launched its “Accessing Justice” project, examining gender-based violence in Latin America from a rule of law lens.

During her historic campaign, president-elect Sheinbaum suggested she’s “uniquely qualified to bring peace,” pointing to her track record as mayor. She has her work cut out for her. Her candidacies—for mayor and president— broke barriers for women in terms of their engagement in the political process. But violence against women—especially those running for office—represent new barriers that could undo the progress of which Mexico is so very proud.

This blog was researched and drafted with support from Camilla Reitherman and Katherine Schauer.

Author

Mexico Institute

The Mexico Institute seeks to improve understanding, communication, and cooperation between Mexico and the United States by promoting original research, encouraging public discussion, and proposing policy options for enhancing the bilateral relationship. A binational Advisory Board, chaired by Luis Téllez and Earl Anthony Wayne, oversees the work of the Mexico Institute. Read more

Explore More in Stubborn Things

Browse Stubborn Things

Spying on Poachers

China and the Chocolate Factory

India: Economic Growth, Environmental Realities