A blog of the Polar Institute

The Alaska Center of Conservation Science (ACCS) is a small (yet capable!) group of ecologists housed at the University of Alaska in Anchorage. We are here because we believe in what we do—providing the scientific basis for responsible, effective land management across Alaska. And while this work is vital, it also grants us the privilege to explore some of the last untouched wilderness on earth.

One of these remarkable places is the Arctic Coastal Plain.

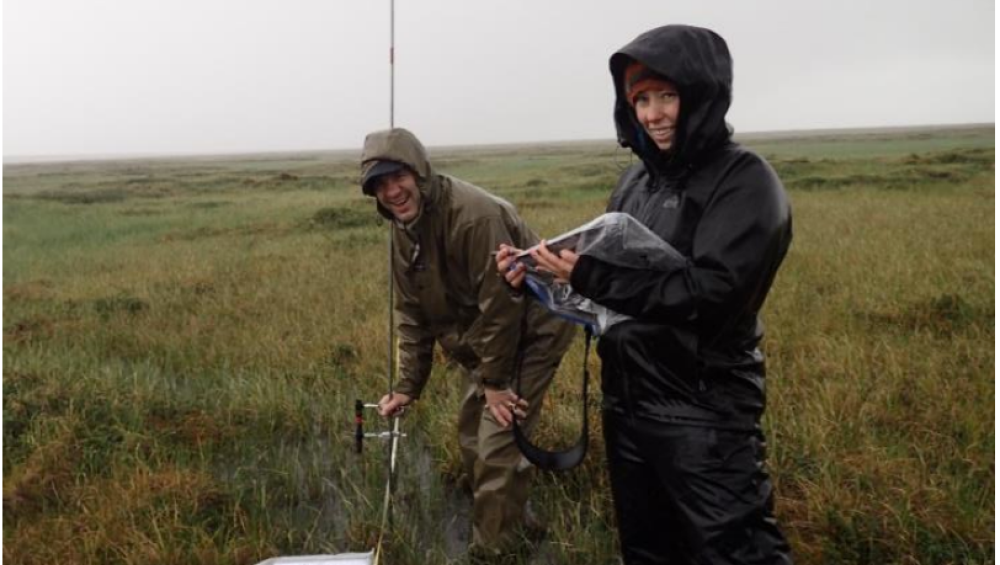

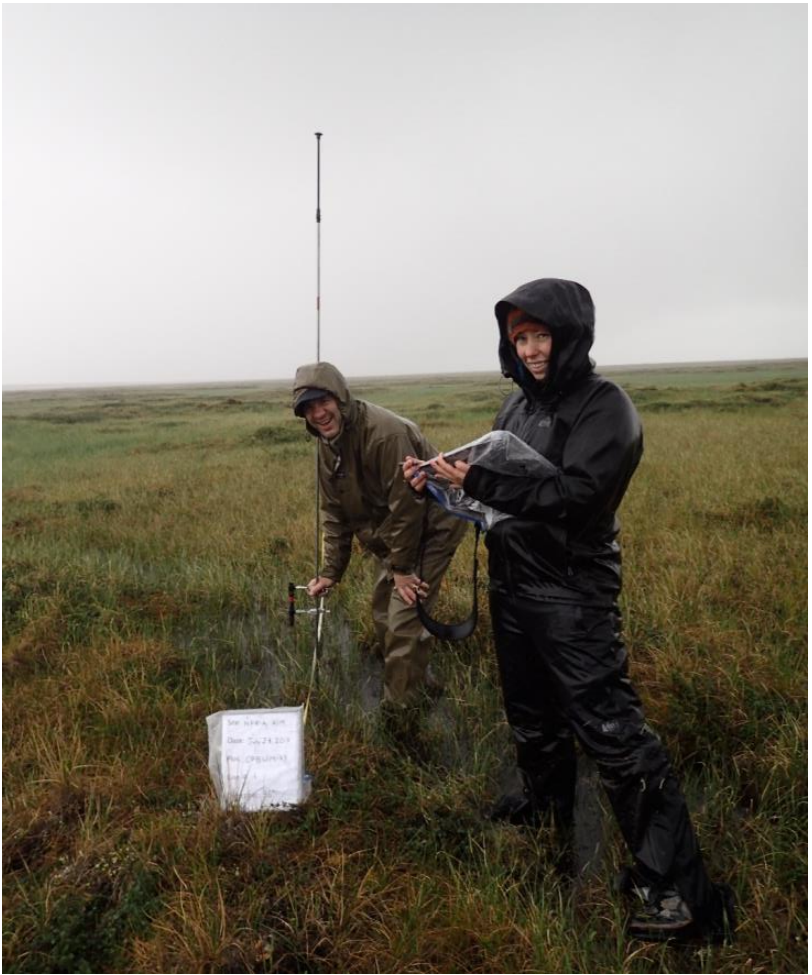

Over a decade ago, our research center was approached by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to adapt a monitoring program, originally developed for arid rangelands in the intermontane west, to permafrost landscapes in Alaska. Ironically, it would be hard to identify two more disparate systems. In the west, field crews were battling a hot and dry climate to quantify the distribution of sagebrush. But in the north, the BLM was asking us to battle the wet and cold to measure the depth to permanently frozen ground—and that is just to name a few of the different metrics! Nonetheless, it was a welcomed challenge that over the years has flourished to a productive partnership that continues to provide key information for the effective management of Arctic lands.

In the Arctic Coastal Plain, beyond the coastal fringe of oil and gas development, you can walk a long time without crossing a trail, never mind a road or airstrip; you’re more likely to come nose to nose with a caribou, than another human. Yet despite its distance from human activity, the effects of a changing climate are concentrated here, making the need for the adapted monitoring program such a high necessity. High latitudes are warming at twice the rate of more temperate regions, resulting in reduced cover and residence of sea ice, increased power and frequency of coastal storms, a longer growing season, and warming permafrost. This is some of what our data tracks.

Most notably, the influence of permafrost in the Arctic cannot be understated.

Where ice fills the pore space between soil particles, permafrost forms an impermeable layer that may start only 20 cm below the ground surface, yet its range (thermal regime) may extend to over 180 m. The impact? The permafrost’s geothermal heat overrides the surface effect of climate.

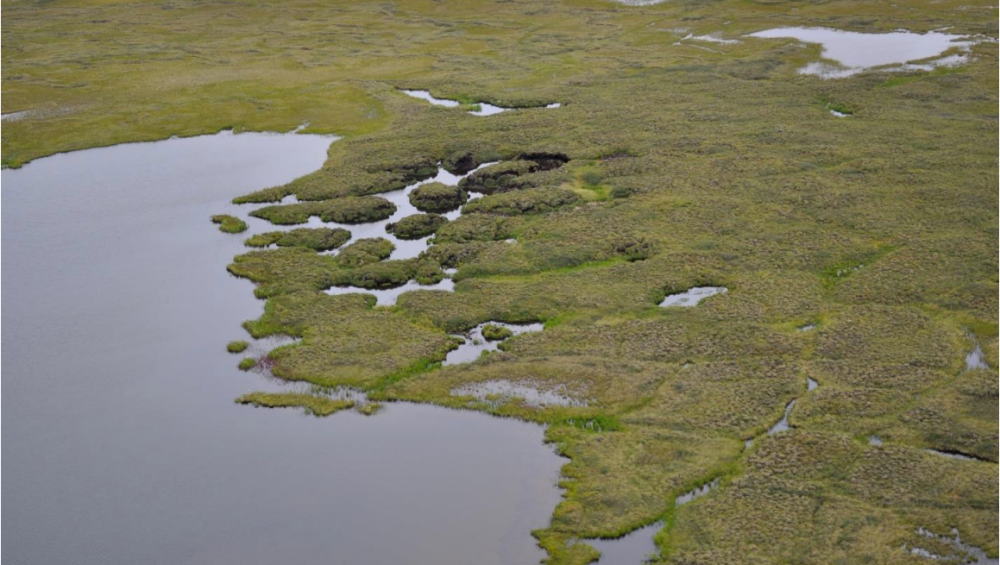

Because of this, the presence of ice-rich permafrost has major implications for drainage, plants, and soils. Across the gentle topography of the Arctic Coastal Plain, precipitation is neither readily drained by topography nor accommodated by shallow soils. The result is a waterlogged habitat where plants employ a variety of adaptations to grow and reproduce. For example, obligate wetland plants, equipped with specialized oxygenated tissues grow in the wettest, anoxic areas. Tussock-forming sedges build mounds to elevate their own roots above saturated soils and in turn, provide sites for the establishment of plants that cannot tolerate waterlogging, such as dwarf shrubs and lichens.

Arguably the most important consequence of permafrost is carbon sequestration. Because the rate of decomposition is slowed by cold and wet conditions, organic matter accumulates as thick deposits of peat. The storage of carbon as peat prevents it from being released to the atmosphere as carbon dioxide or methane—two important greenhouse gases. Without being properly released in these forms, the carbon cycle is restricted and so is the consequence of slowing the rate of climate warming.

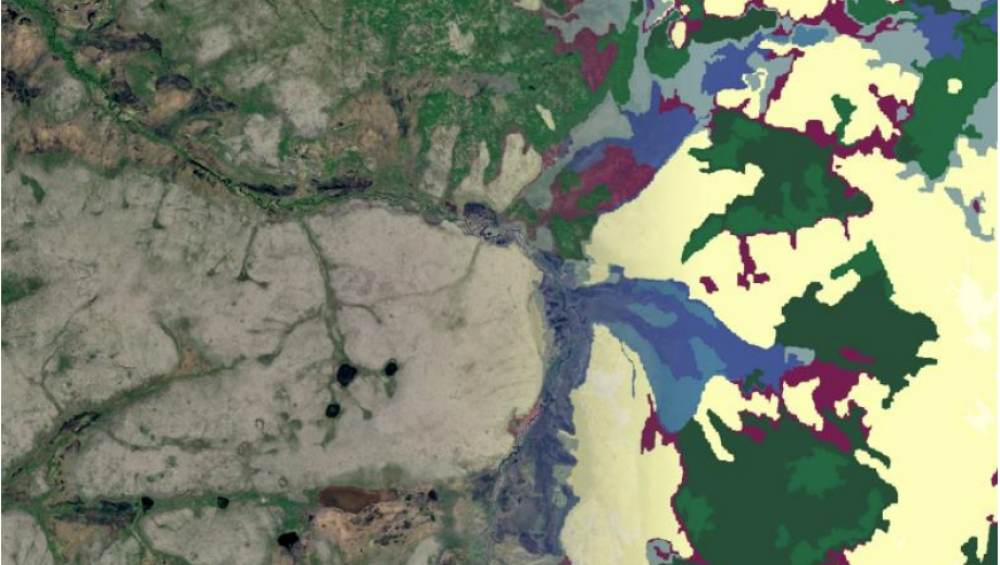

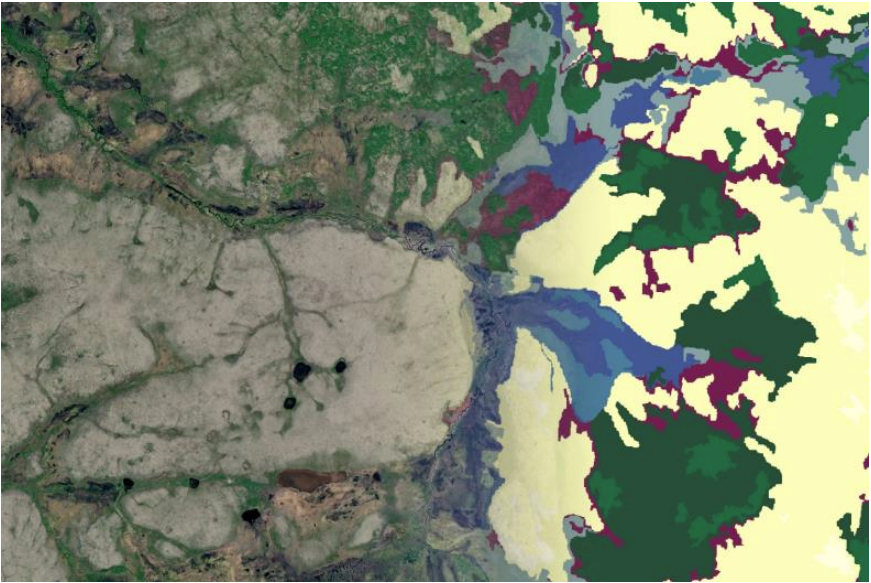

Data on both permafrost and carbon sequestration is just some of the large amounts of data the monitoring program collects in the Arctic Coastal Plain. The data we collect on the ground is ultimately used in combination with remotely-sensed imagery to produce fine-scale maps of surface condition related to permafrost, surface water, vegetation, productivity, and phenology. Because the generation of these maps is repeatable from current imagery, they provide a real-time, affordable measurement of natural resource conditions and trends.

In a few years, the models used to produce the maps will be rerun with current imagery inputs so that areas of change can be identified, and land management actions can be adapted as necessary. Long-term monitoring efforts such as these are critical to inform policy actions that will strengthen climate resiliency in the Arctic for decades to come.

Photos from the Field

Photos taken by ACCS staff and provided by Lindsey Flagstad.

Author

Polar Institute

Since its inception in 2017, the Polar Institute has become a premier forum for discussion and policy analysis of Arctic and Antarctic issues, and is known in Washington, DC and elsewhere as the Arctic Public Square. The Institute holistically studies the central policy issues facing these regions—with an emphasis on Arctic governance, climate change, economic development, scientific research, security, and Indigenous communities—and communicates trusted analysis to policymakers and other stakeholders. Read more

Explore More in Polar Points

Browse Polar Points

Downlink Dispatch: Notes on Space from the North | Part 1