A blog of the Kennan Institute

In the third year of Russia’s full-scale war, with the destruction of Ukraine’s economic potential and increasing government debt, the question on the minds of Ukrainians and Ukraine’s partners is whether a default can be expected. The answer is no, at least not yet. Several steps can be taken to avoid default, including restructuring some debt and negotiating lower interest rates and lower debt service payments. The best action, Russia’s cessation of aggression, is not envisioned in the immediate future debt scenarios.

Ukraine’s Debt Picture

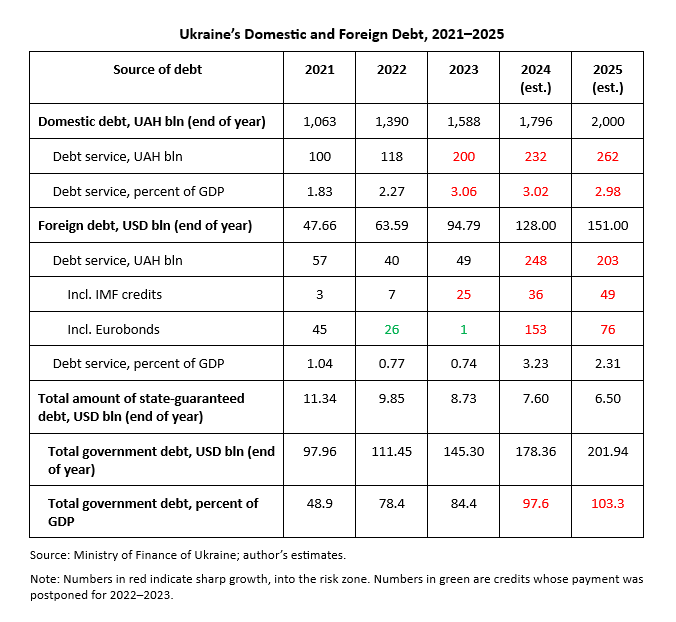

Before the war, Ukraine was in a fairly good debt position, having a low government debt of only 48.9 percent of GDP at the end of 2021. The average rate of debt service was about 9 percent per annum on domestic debt and 4 percent on foreign debts. The total cost of debt service was equal to 2.9 percent of GDP.

But the decline of the Ukrainian economy as a result of Russia’s invasion, together with a significant increase in public spending, which rose from 40 percent to 75 percent of GDP from 2021 to 2023, greatly increased both domestic and foreign debt. As a result, at the end of 2023, public debt was 84.4 percent of GDP. This figure would have been even worse had the United States not fleshed out Ukraine’s budget with $22.85 billion in grants, not credits, in 2022–2023.

In 2022, Ukraine reached an agreement with its creditors to postpone payment of the principal and interest on Eurobonds for 2022–2023. In 2024 the situation is different, however. This year Ukraine has no Western grant support, while the time has come to pay interest on Eurobonds for three years at once (for 2022–2024).

This situation has resulted in an unprecedented increase in public debt servicing costs to 6.3 percent of GDP, or almost $12 billion in 2024. And the public debt at the end of the year will reach almost 100 percent of GDP (97.6 percent, per my current forecast). At the same time, the National Bank of Ukraine’s high interest rate policy has meant an increase in average domestic debt service rate from 9 to 13 percent in two years.

Servicing Debts to the IMF and Other Creditors

Ukraine, having signed a four-year program with the IMF, is now replacing $10 billion of debt to the IMF (debt that was incurred before the war at rates of 2 or 3 percent per annum) with another IMF credit of $15.6 billion (bearing interest rates of about 8.5 percent per annum). As a result, already in 2024, Ukraine, in addition to repaying the loan principal under the old IMF programs, will have to pay about $900 million in interest to service the IMF debts. According to calculations, having received $5.4 billion in loans from the IMF in 2024, Ukraine will need to increase the debt service payments in 2025 up to $1.1–1.2 billion.

In addition, there are Ukraine’s 2015 GDP-linked securities, which are valid until 2041. In 2015, Prime Minister Yatsenyuk and Finance Minister Yaresko signed an agreement with creditors that slightly reduced the amount of debt in exchange for securities, payments for which are required if Ukraine’s economic growth exceeds 3 percent of GDP, beginning in 2019. The greater the growth, the greater the payout. Under conditions of postwar reconstruction, payments on these obligations could reach $1–$2 billion per year or more, with a nominal volume of securities of $3.2 billion.

In 2023, the Ukrainian economy grew 5.3 percent, which means that already in 2025, Ukraine will have to pay, according to my estimates, $700–$800 million in “tax on the growth of the Ukrainian economy” in favor of creditors—something that the Ministry of Finance has been keen to avoid mentioning for years.

Thus, approximately half of the U.S. and EU aid to Ukraine in 2024 will go toward servicing debt owed creditors inside and outside Ukraine.

To lessen the burden for the state budget, in May–June 2024 the Ministry of Finance and Ukraine’s creditors held talks on restructuring $20 billion of debt (Eurobonds) and modifying GDP-linked securities. So far the talks have not led to any common decision. If the debt restructuring is not successful by August 1, 2024, Ukraine will have to pay about $3.75 billion on the Eurobonds by the end of 2024.

Does This Mean Ukraine Will Default in 2024?

No. This $3.75 billion Eurobond payment is included in Ukraine’s 2024 budget.

Nonetheless, it is obvious that the longer the war drags on, the closer Ukraine will come to defaulting. Already in 2025, the national debt is projected to exceed 100 percent of Ukraine’s GDP.

Steps to Avoid Defaulting

To minimize the risk of Ukraine defaulting in the next few years, the government should undertake the following steps:

1. Restructure the Eurobond debt, aiming for partial debt remission, minimization of interest payments, and deferral of the start of payments from 2024 to 2025. These measures would allow Kyiv to deal with financial issues this year.

2. Restructure (or get a redemption of) Ukraine’s GDP-linked securities through 2041. Ukraine’s postwar recovery will be limited by the fact that its future economic growth will be tied up in the obligation to pay 0.5–1 percent of GDP per year on such securities.

3. Negotiate to restructure—or even partially cancel—the IMF debt. Interest rates for this credit should be reduced from 8–9 percent to the prewar rates of 2–3 percent per annum.

4. Change NBU policies to significantly reduce the rate paid by the NBU on certificates of deposit. This would increase the profits paid into the state budget by the NBU, which in turn would reduce the cost of new domestic borrowing and the cost of servicing previous domestic debt.

The opinions expressed in this article are those solely of the author and do not reflect the views of the Kennan Institute

Author

Kennan Institute

After more than 50 years as a vital part of the Wilson Center legacy, the Kennan Institute has become an independent think tank. You can find the current website for the Kennan Institute at kennaninstitute.org. Please look for future announcements about partnership activities between the Wilson Center and the Kennan Institute at Wilson Center Press Room. The Kennan Institute is the premier US center for advanced research on Eurasia and the oldest and largest regional program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Explore More in Focus Ukraine

Browse Focus Ukraine

Talking to the Dead to Heal the Living

Ukrainian Issue in Polish Elections