Kennan Cable No. 56: No Great Game: Central Asia’s Public Opinions on Russia, China, and the US

Great power competition has reignited between the US, China and, to a large extent, Russia. Central Asia emerged early on as an arena for this trilateral contest. The region has often been a hub of influence over Eurasia, or at least has been seen as one. It is indeed highly important for a rising China, which began extending its influence there in the mid-1990s through what would become the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. It is also key for Russia, as Moscow seeks to lead regional integration and reassert its status as Eurasian pivot.

But, while the region also once drew substantial US attention and (mostly military) presence, the US's position there is now clearly a shadow of what it was in the early 2000s. Russia and China, meanwhile, have established a thus far well-functioning division of labor in the region. Central Asia thus appears as a microcosm of the great power triad: the Sino-Russian partnership first formed there, while the decline in US influence was perhaps visible in Central Asia even before it was clear that the American position was beginning to weaken globally. Central Asia may therefore be a prototype for the post-unipolar world, demonstrating how it emerges and how it looks.

Yet Central Asian countries are not passive pawns in a Great Game between Washington, Beijing, and Moscow. Their governments have shown remarkable resilience to external pressure, and have exploited the great powers' competition to consolidate their rule, yielding what Alexander Cooley has dubbed “Great Games, Local Rules.”[1] But while we know much about official doctrines of “crossroads,” Eurasianism, Silk Roads, multivectoralism, perpetual neutrality, etc., we understand little about the beliefs of ordinary Central Asians. [2]

To begin filling this gap, we analyze here two sets of as-yet largely-unused data: 1) surveys conducted by the Central Asia Barometer in all five Central Asian countries between June 2017 and November 2019, and 2) the 2017 Integration Barometer survey of the Eurasian Development Bank (conducted in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan). [3] They paint a relatively clear picture of three great but unequal powers: Russia enjoys evident dominance in public opinion, China is in a relatively well-regarded second place, and the US comes in decidedly last.

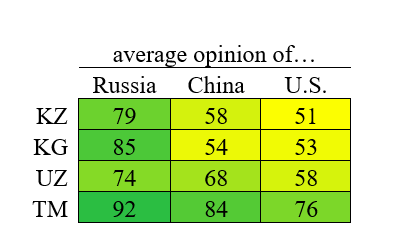

Central Asian Public Opinion of the Great Powers

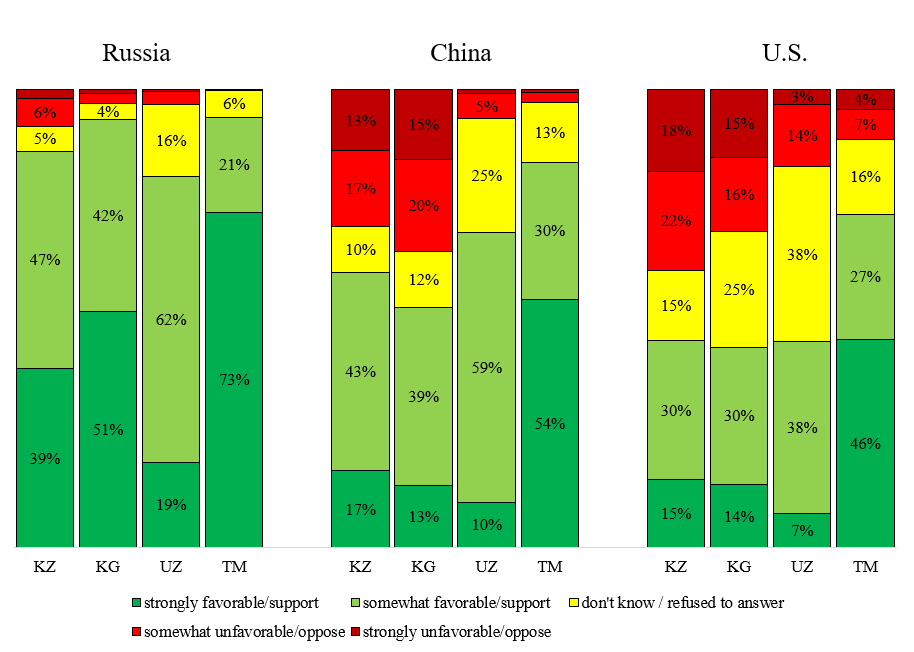

In Kazakhstan, Russia holds a large lead, with China far behind, and the US slightly further still. In Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, the order remains the same, but the gaps are substantially smaller. Kyrgyzstan differs in that its opinion of China is worse than anywhere else, and thus no better than its opinion of the US.

Average Opinion in Each Central Asian Country of Each Great Power

Source: Average result of all six CAB waves (June 2017 – November 2019), or of the last three CAB waves (November 2018 – November 2019) in the case of Turkmenistan.Displaying respondents' average answer (0-100 scale), with "very unfavorable", "somewhat unfavorable", don't know / refused to answer, "somewhat favorable", and "very favorable" assigned values of 0, 25, 50, 75, and 100, respectively.

Opinions of each great power, by Central Asian country

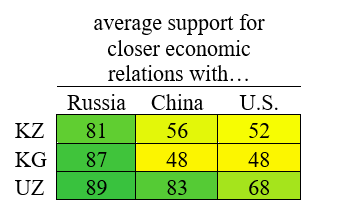

Preferences for economic relationships follow almost exactly the same pattern. The only difference is that Uzbek opinion of closer economic relations with China is almost as (overwhelmingly) positive as its opinion of closer economic relations with Russia, as a result of which China's position is much closer to Russia's than to the US's.

Average support in each Central Asian for closer economic relations with each great power

Displaying respondents' average answer (0-100 scale), with "strongly oppose", "somewhat oppose", don't know / refused to answer, "somewhat support", and "strongly support" assigned values of 0, 25, 50, 75, and 100, respectively.

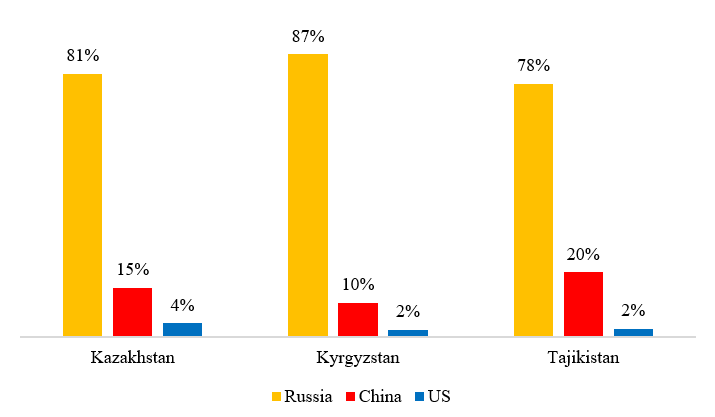

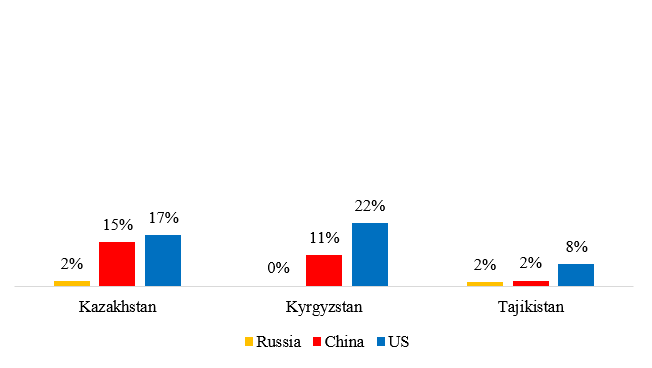

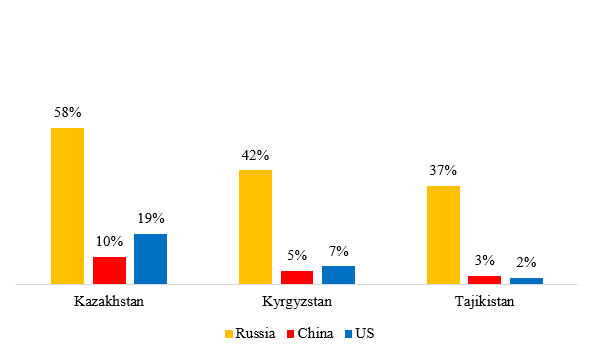

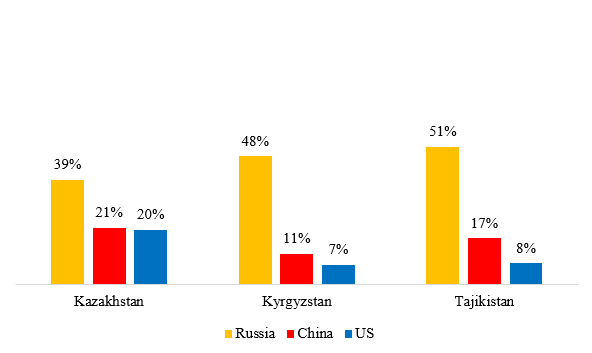

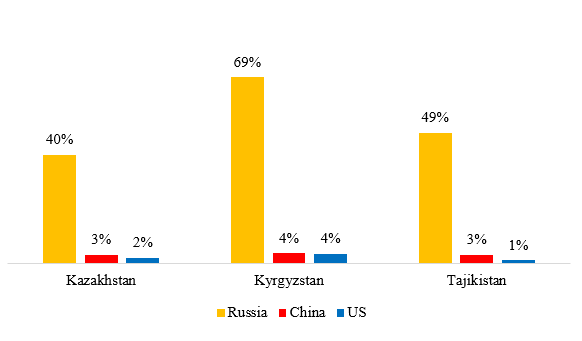

The same general pattern is also observable in the Eurasian Development Bank's 2017 Integration Barometer survey:

Proportion of respondents in each Central Asian naming each great power as friendly and reliably helpful

Proportion of respondents in each Central Asian naming each great power as unfriendly and threatening

In Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan (the survey was not conducted in Uzbekistan or Turkmenistan), Russia is overwhelmingly seen as a friendly/reliable/helpful country, opinion on China is mostly neutral and about evenly split, and opinion of the US is modestly net-negative. The same patterns hold in Tajikistan (for which we have no CAB data), with the exception that the positions of the US and China are, respectively, slightly and significantly improved. Indeed, a pattern is observable here and elsewhere, according to which public opinion of China is more positive in Tajikistan than in Kazakhstan or Kyrgyzstan.

Evaluating Soft Power Influence

There are some specific areas, however, in which the Russia-China-US order partly breaks down. This demonstrates, among other things, that general perceptions and various specific preferences are not reliably linked.

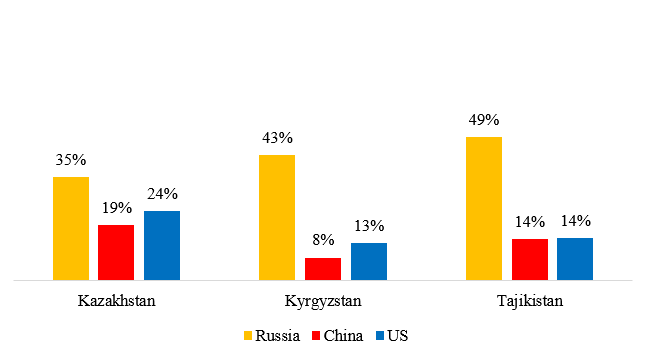

For instance, Russia is the most popular educational destination amongst Kazakhstanis, but China and the US are close behind. That said, Kazakhstanis' ideal preferences diverge greatly from their actual behavior, probably at least in part because an education in Russia is in practice far more accessible: of the 89,000 Kazakhstani students studying abroad in 2018, 69,000 (78 percent) were in Russia.[4] In contrast, of Kazakhstanis who identified at least one country as a place where they would like to study or they would like their children to study, only 35 percent mentioned Russia either alone or alongside other destinations.

Additionally, as a destination for study or work, the US is either tied with or ahead of China in all three countries. This may reflect the English language's enduring (or at least perceived) global predominance.

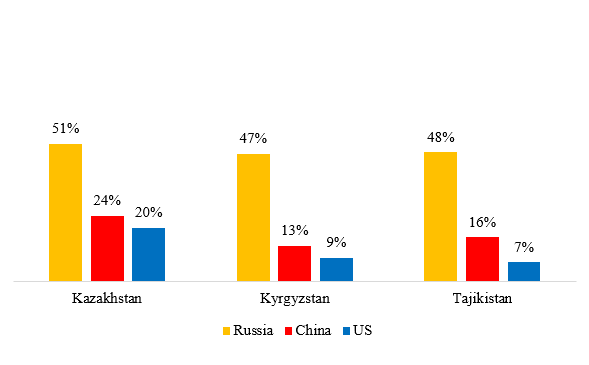

Proportion of respondents in each Central Asian naming each great power as a country where they would like to study or send children for study, out of respondents who named any destination

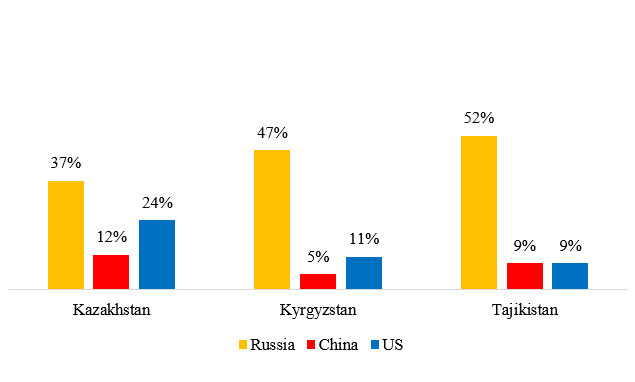

The same pattern holds for labor migration. The strength of the US dollar, as well as the greater (actual or perceived) wealth of the US economy, may be partly responsible for the US's relative popularity as a labor market. And the prevalence of actual labor migration to Russia from Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan may be the reason for Russia's popularity in this category.

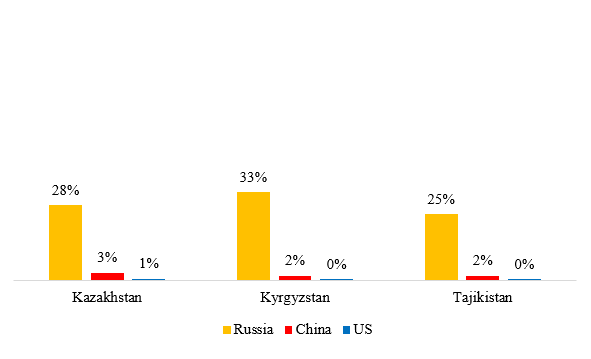

Proportion of respondents in each Central Asian country naming each great power as a country where they would like to work, out of respondents who named any destination

(Note that, while these questions explicitly ask respondents where they would like to work if they had the opportunity, it is not clear to what extent responses are affected by respondents' judgement regarding which options are actually realistic for them.)

The US's lead over China, or at least equivalence to it, also extends to the popularity of the great powers' cultural presence. Neither, however, come close to the influence of Russian culture, which holds a large lead not only in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan but also in Kazakhstan. Russia remains a central cultural yardstick for Central Asians, even if competition is growing from Turkish, South Korean, Indian, and Japanese cultural products that are especially attractive to younger generations.[5] China’s soft power, on the other hand, is quite weak across Central Asia.[6] Surveys of Confucius Institute students, as well as anecdotal evidence, suggest that Kazakhstanis and Kyrgyzstanis seek to learn the Chinese language but not to learn about China itself, with very few attending classes on Chinese culture and history.[7] Whether the Institutes can create a positive image of China thus remains to be seen. As for US soft power, its effects are highly contradictory: US films, music, and other cultural products are relatively widespread in Central Asia, but also draw a great deal of criticism across the region for conveying foreign, liberal values.[8]

Proportion of respondents in each Central Asian country naming each great power as a country from which their own should "invite more musical artists, writers, and artists, and import and translate more books, films, music, and other cultural productions"

In matters of business and science, the overall Russia-China-US pattern returns with China regaining its second-place position while Russia retains a fairly large lead (albeit one that is somewhat smaller in Kazakhstan on the question of investment and business).

Proportion of respondents in each Central Asian country naming each great power as a country from it is "desirable for our country to receive capital, investments, companies, and businessmen who will set up their enterprises here"

Proportion of respondents in each Central Asian country naming each great power as a country with which "our government and/or companies should cooperate in science and technology; conduct joint research, exchange designs, technologies, and scientific ideas"

The question on culture explicitly asked about the desirability of increased ties, while the other two questions' discussion of hypotheticals may similarly have caused respondents to think about the degree to which ties additional to those already existing would be desirable. Insofar as this is the case, countries (namely Russia, and to a lesser extent China) could be “penalized” for having relatively large presences already.

Inside the Numbers

On every topic, perceptions of Russia are the most positive in all five countries. The three Central Asian countries most closely linked to Russia are Kazakhstan (member of the Collective Security Treaty Organization and the Eurasian Economic Union), Kyrgyzstan (CSTO and EAEU), and Tajikistan (CSTO). In those three, the gap is widest between Russia and China/US The gap is somewhat narrower in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, but that is largely because of better views of China and the US Positive overall opinions of Russia, support for closer economic relations with it, and perceptions of it as a friendly and helpful country are all held almost unanimously in the countries polled on those matters. Substantial variation in opinion of Russia is observable only in that it appears to be culturally somewhat more attractive in Kazakhstan than in Kyrgyzstan or Tajikistan, while Russian investment and business ties, and Russia as a destination for work and education, are somewhat more attractive in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan than in Kazakhstan.

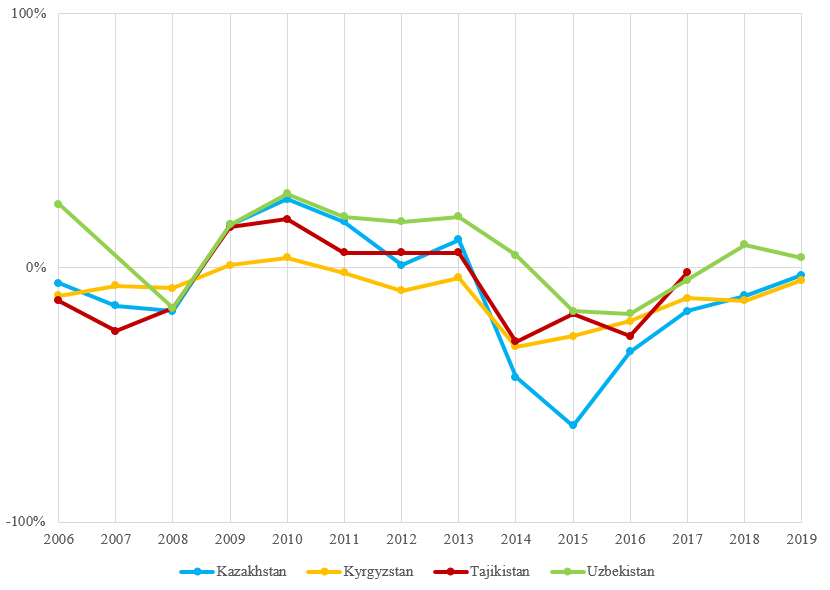

One partial cause of Central Asians' positive opinions of Russia is likely the far greater level of personal connections that they have to it. Far more respondents from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan have visited Russia within the last five years than have visited either China or the US in that same period.

Proportion of respondents in each Central Asian country who named each great power as a country that they have visited within the last five years

The difference is even starker with regard to the presence of relatives, friends, and colleagues living abroad in the three countries. For Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, this is surely in part a result of widespread labor migration to Russia. And for Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, it is an unsurprising result of the substantial freedom of movement that is provided by membership in the Eurasian Economic Union.

Proportion of respondents in each Central Asian country who named each great power as a country where there are relatives, friends, colleagues, etc. with whom the respondent keeps in contact

As for China, it is well behind Russia everywhere (except perhaps Uzbekistan), yet ahead of the US However, many Central Asians remain wary: in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, equal numbers see China as a friend and as a threat or enemy. Only in Tajikistan does a positive view of China predominate. In part, this is likely because Dushanbe has fewer economic partners to rely on. Since it lacks membership in the Eurasian Economic Union and does not consider economic support from Russia to be sufficient, Tajikistan values Chinese investments more highly. Additionally, public discussions of a Chinese demographic threat are less prominent in Tajikistan than they are in the country's northern neighbors, even if tensions around border delimitation and territorial cessions to China regularly arise.[9]

Opinions of China and of closer economic relations with it are most positive in Turkmenistan, then Uzbekistan – the two countries which lack a border with China and whose populations express fewer concerns about China’s proximity – then in Tajikistan, and finally least positive (or outright ambivalent) in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. In more specific areas, China's strengths are clearly in business and technology, while the country ties with or actually lags behind the US as a desired source of culture and arts and as a desired destination for work or study.

China's policies in Xinjiang are likely one cause of its problems. Its re-education camps and other measures of control over the region's Muslim Turkic population, including Uyghurs and Kazakhs, are not well-received in Central Asia – particularly in Kazakhstan (which has a large Uyghur minority) and Kyrgyzstan. Kazakh complaints about Beijing's policies have grown in recent years from both the public and government officials.[10]

The US is clearly in third place. The generally mixed opinion reflected in US scores on these surveys puts it well behind Russia and even China. The gap is slightly larger still on the question of closer economic relations. More people see the US as foe than as friend in all three countries polled on the question. Taking this decidedly mixed overall image into account, the US is surprisingly popular in Kazakhstan, relative to Russia, as a destination for study and work, and as a source of investment, business, science, and technology. On the other hand, it performs less well relative to Russia in terms of culture: its overall image is actually worse in Kazakhstan than anywhere else polled, and Kazakhstanis are barely more supportive than Kyrgyzstanis are of closer economic relations with the US (which is to say, quite ambivalent). As with China, overall sentiment towards the US is most positive in Turkmenistan, followed by Uzbekistan, then Tajikistan, and finally decidedly ambivalent in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

Why the poor US performance? [11] Three factors that might sound plausible are actually wrong.

First, although perceptions of the US have worsened under President Trump throughout much of the world, Central Asia is one exception. As Gallup reported in 2018, Central Asian opinion of the US leadership's job performance actually improved when Trump entered power.[12] And annual Gallup World Poll surveys indicate that this opinion has continued to improve, reaching levels that rival the highest ratings in years.

Second, as we argue elsewhere, Central Asian opinion – whether of the US or of Russia – probably cannot be attributed to Russian-origin media's large presence in the region. Whether Central Asians rely mainly upon Russian-origin media as their primary source of news, or mainly upon domestic-origin alternatives instead, does not make a significant difference in their opinions of the US or Russia.[13] Thus, Central Asian opinion appears to be domestically-produced. If it is at all a product of "Russian influence," then that influence is so deeply ingrained within the societies that differentiating it may be both impossible and nonsensical.

Third, opinion of the US is probably not being "crowded out" by opinion of Russia in some sort of contest between mutually-exclusive alternatives. To the contrary, 2017-2019 polling data from the Central Asia Barometer suggests that views of the US and Russia are, if anything, positively correlated. We conducted 34 regression analyses correlating opinions of the US and of Russia, opinions of closer economic relations with the US and of closer economic relations with Russia, and opinions of US President Trump and of Russian President Putin. These analyses were performed on public opinion in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan. (The necessary data are not available for Tajikistan.) They featured an exhaustive list of control variables, and when possible were duplicated with the inclusion of a variable controlling for average opinion of other Central Asian countries/rulers. Opinions of the US and Russia (or of closer economic relations with the two, or of the leaders of the two) were positively correlated in all but two regressions. In those two cases, the effects were substantively small and statistically insignificant. Conversely, 26 of the 32 positive relationships were statistically significant. These results indicate, at the very least, that positive opinions of the US and Russia are not contradictory or mutually-exclusive in Central Asia.

Conclusion

The Central Asian states' officially-proclaimed foreign policies are well-known. The countries adhere to a diplomatic officialese that celebrates the region's status as a "crossroads" between East and West. Kazakhstan has successfully associated itself with multivectoralism and Eurasianism, and all five countries to some extent endorse the Chinese-backed Silk Road project that places them at the heart of a revived continental trade network. All five states push back against US pressure on human rights, rule of law, and good governance, and Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan sometimes criticize Russia's regional policies. They rarely if ever speak ill of China.

Central Asian public opinions paint a somewhat different picture. Public perceptions of Russia are quite positive, perhaps even more than the diplomatic relations and elite opinions might indicate. This is partly caused by uniquely dense people-to-people relationships, producing an exceptional breadth of positive opinion that extends well beyond views of the Russian government to social, cultural, and economic areas. The opposite applies to the US: the country is generally perceived worse than (already cool) official relations and elite opinion would suggest. In part, this is likely because the US has few people-to-people contacts and is really attractive on only a narrow range of topics – namely education, science, and technology. Public and official opinions diverge the most with regard to China. While Beijing is officially celebrated by all the Central Asian governments as a welcome partner, domestic opinion, particularly in China's immediate neighbors, remains skeptical of it and largely resistant to its soft power – a situation to which Beijing has adapted with the axiom “warm politics, cold public” (zheng re, min leng).[14]

However, in the long run, public opinion is likely to significantly shape, or at least constrain, the policies of the Central Asian states towards the great powers. Thus, for those powers, a positive public image constitutes a real asset in the competition for regional influence, a struggle whose outcomes are still not yet fully determined.

This article is part of a project with Eric McGlinchey, on Russian, Chinese, Militant, and Ideologically Extremist Messaging Effects on United States Favorability Perceptions in Central Asia, funded by the US Department of Defense and the US Army Research Office/Army Research Laboratory under the Minerva Research Initiative, award W911-NF-17-1-0028. The views expressed here are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the US Department of Defense or the US Army Research Office/Army Research Laboratory.

[1] Alexander Cooley, Great Game, Local Rules: The New Great Power Contest in Central Asia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

[2] See, for instance, Luca Anceschi, Analysing Kazakhstan’s Foreign Policy Regime. Neo-Eurasianim in the Nazarbayev Era (London: Routledge, 2020), and, same author, Turkmenistan’s Foreign Policy. Positive Neutrality and the Consolidation of the Turkmen Regime (London: Routledge, 2008).

[3] Between June 2017 and November 2019, the Central Asian Barometer (CAB) conducted six (three in Turkmenistan) surveys of public opinion in each of the five Central Asian republics. However, the questions of interest to us were not asked in Tajikistan.

[4] UNESCO. 2019. “Global Flow of Tertiary-Level Students,” http://uis.unesco.org/en/uis-student-flow.

[5] Marlene Laruelle, ed, The Nazarbayev Generation. Youth in Kazakhstan (Lanham, MD: Lexington, 2019).

[6] See, for instance, Darmen Koktov, “The Sources of Anti-Chinese Sentiment in Kazakhstan Through the Prism of Anti-Americanism,” Central Asian Affairs, forthcoming. See also Sébastien Peyrouse, "Discussing China: Sinophilia and Sinophobia in Central Asia," Journal of Eurasian Studies 7, no. 1 (2016): 14-23.

[7] Gaukhar Nursha, "Chinese Soft Power in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan: A Confucius Institutes Сase Study", in Marlene Laruelle, ed, China’s Belt and Road Initiative and its Impact in Central Asia (Washington DC: GW’s Central Asia Program and Nazarbayev University, 2018), 135-143.

[8] Marlene Laruelle, Dylan Royce, “Failing the Test? US Soft Power in Kazakhstan,” forthcoming.

[9] Bradley Jardine and Edward Lemon, “In Russia’s Shadow: China’s Rising Security Presence in Central Asia,” Kennan Cable 52, May 2020; see also Steven Parham, “The bridge that divides: local perceptions of the connected state in the Kyrgyzstan–Tajikistan–China borderlands,” Central Asian Survey 35, no. 3 (2016): 351-368.

[10] Bruce Pannier, "Kazakhstan Confronts China Over Disappearances", Radio Free Europe, 1 June 2018, www.rferl.org/a/qishloq-ovozi-kazakhstan-confronts-china-over-disappearances/29266456.html

[11] Marlene Laruelle, Dylan Royce, “Failing the Test? US Soft Power in Kazakhstan,” forthcoming.

[12] Julie Ray, "World's Approval of US Leadership Drops to New Low", Gallup, January 18, 2018, news.gallup.com/poll/225761/world-approval-leadership-drops-new-low.aspx

[13] Marlene Laruelle, Dylan Royce, “Russian media influence in Central Asia: Easy to imagine, difficult to find,” All the Russias Blog (NYU Jordan Center), jordanrussiacenter.org/news/russian-media-influence-in-central-asia-easy-to-imagine-difficult-to-find/

[14] David Kerr, “Central Asian and Russian perspectives on China’s strategic emergence,” International Affairs 86, no. 1 (2010): 127–152.

Authors

Director and Research Professor, Institute for European, Russian and Eurasian Studies (IERES), Elliott School of International Affairs; Director, Central Asia Program, The George Washington University; Co-Director of PONARS (Program on New Approaches to Research and Security in Eurasia)

Kennan Institute

The Kennan Institute is the premier US center for advanced research on Eurasia and the oldest and largest regional program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

US Inaction Is Ceding the Global Nuclear Market to China and Russia

Promoting Convergence in US-Brazil Relations