North Korean Perspectives on the Overthrow of Syngman Rhee

***

NKIDP e-Dossier no. 13, "North Korean Perspectives on the Overthrow of Syngman Rhee, 1960," is introduced by Jong-dae Shin, Christian F. Ostermann, and James Person and features twenty translated documents cataloging North Korea’s immediate responses to the April 19 Revolution in South Korea and how the DPRK attempted to take advantage of the events which ultimately led to the resignation of President Syngman Rhee.

To view the twenty translated documents, please click here or see the link below.

***

North Korean Perspectives on the Overthrow of Syngman Rhee, 1960

Introduction by Jong-dae Shin, Christian F. Ostermann, and James Person

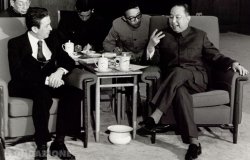

The close attention which North Korea paid to the popular protest movement in South Korea in the spring of 1960 is made vividly clear in the journals left behind by Aleksandr Mikhailovich Puzanov, then Soviet Ambassador in Pyongyang. Puzanov’s diaries—an important selection of which has been translated and reproduced below—catalogue North Korea’s immediate responses to the demonstrations which began in the wake of the fraudulent March 1960 presidential election in South Korea, and how the DPRK attempted to take advantage of the events both before and especially in the wake of President Syngman Rhee’s resignation.

Following the contested March 1960 election, demonstrators took to the streets in cities such as Seoul, Busan, and Daegu. Concurrently, the leadership in Pyongyang began to take stock of the widening protest movement and debated the strength of the “revolutionary forces” in South Korea. From Puzanov’s diaries it is clear, however, that the Korean Workers’ Party did not initially anticipate the resignation of Syngman Rhee. It was only after the events of April 19, 1960, which led to the overthrow of the First Republic, that North Korea realized that Rhee’s resignation was within the realm of possibilities.

North Korea understood the April 19 Revolution as an implosion of “social contradictions” under the “imperialistic rule” of the United States and took the fall of the Rhee administration as the first victory in the anti-American struggle in South Korea. Pyongyang’s leaders believed that the economic development of North Korea and the broader socialist camp contributed to the unrest in South Korea, and the Korean Workers’ Party called on the North Korean population to step up efforts to construct a socialist society and aid the cause in the South. However, North Korea also maintained that despite the transition from Syngman Rhee to the Jang Myeon administration, there could be no real change in South Korea without the withdrawal of US forces from the Peninsula.

Pyongyang also identified other factors which led to an overall weakened protest movement in South Korea. Disappointingly, the North Korean leadership suggested that the April 19 Revolution did not develop into an actual revolution because there was no leading party in Seoul and because of defects in the workers and peasants movements. Nevertheless, North Korea did find encouraging signs in the April 19 Revolution. Pyongyang, for example, had new confidence in the South Korean student movement and believed that students would make up for the deficiencies of the workers and peasants. Through the April 19 Revolution, North Korea also identified various reformist organizations in South Korea and attempted to establish contacts with these groups in order to facilitate Korea’s peaceful reunification.

Puzanov’s diaries make explicit North Korea’s proposals for direct North-South exchanges in the wake of the April 19 Revolution. Prime Minister Kim Il Sung even suggested the establishment of a Korean federation in his liberation day speech on August 15, 1960. The federal unification strategy proposed by North Korea was a reflection of how Pyongyang perceived the political and economic gaps between the North and South, South Korea’s general mistrust with the North, and North Korea’s general sense of superiority of their own regime over South Korea.

Puzanov’s journals reveal Kim Il Sung speculating on possible successors to Syngman Rhee. Kim remarked that the United States faced a dilemma, as Jang Myeon and Jang Taek-sang were less than ideal candidates to replace Rhee. Interestingly enough, Kim Il Sung mentioned that leader of the Progressive Party, Jo Bong-am, was executed because Jo made a premature public statement on his party’s platform of “peaceful unification,” and admitted that “we too made a mistake.” (According to Mongolian documents obtained for NKIDP by Onon Perenlei, Kim Il Sung said that “it is regrettable that we voluntarily nipped a proper successor for the post-Syngman Rhee era in the bud by excessively supporting the leader of the Progressive Party, Jo Bong-am, and causing him to be executed”).

The April 19 Revolution also pushed North Korea to revise how it infiltrated into South Korean politics. Realizing that its underground organizations did not play an active role in the course of the April 19 Revolution, North Korea set out to change how it targeted South Korea. For example, Puzanov reveals that the Korean Workers’ Party established a Central Bureau for South Korean Issues to administer policies toward the South. The Central Bureau was to resurrect underground party cells in South Korea while distributing propaganda related to Korea’s peaceful unification. By July of 1960, Kim Il Sung already boasted of having channels of communication with South Korea’s progressive parties such as the Social Mass Party (Sah-heo dang-jung dang) and the Korean Socialist Party, and on having an influence on them. He estimated that “possibly up to 35 deputies from newly-organized parties who are associated with and under the influence of the KWP CC will be elected to the new National Assembly.” North Korea also established a Communist University (Gongsan daehak), another example of how Pyongyang was actively preparing for unification and vigorous North-South exchanges. The university was to train “unification personnel” from among the 100,000 demobilized members of the Korean People’s Army with southern Korean origins, who would be dispatched to the South once cultural and economic exchanges between the two Koreas resumed, which Kim predicted would happen after two-to-three years.

This collection of documents contains the most explicit information available to date on Kim Il Sung’s plans to modify the pro-industrial policies which had been the main thrust of North Korean development since 1953, to light industry and the production of consumer goods during the first Seven-year Plan (scheduled for 1961-1967) to elevate living standards in the DPRK. This was not just to make the North Korean masses more prosperous. Indeed, Kim seems to emphasize more the benefits of improved living standards in North Korea for improving prospects for reunification. The North Korean leader viewed North Korea’s industry and higher living standards as a magnet to attract South Koreans to support the KWP. Kim expressed to Ambassador Puzanov that he believed that South Koreans travelling north of the DMZ after cultural and trade relations were resumed would have the opportunity to witness the DPRK’s prosperity first-hand and would report back to their brethren in the still aid-dependent South. It is a reverse of South Korea’s present-day efforts to reveal its prosperity to citizens of North Korea to highlight Pyongyang’s failed economic policies.

After the April 19 Revolution, the North Korean leaders seemed to have believed that reunification was not only possible, but imminent (with the withdrawal of U.S. troops from South Korea). Moreover, because of North Korea’s relative political and economic stability, Kim believed reunification could be achieved on North Korean terms. Yet, North Korea’s optimism was short-lived. As documents earlier released by NKIDP reveal, in the immediate wake of the May 1961 military coup in South Korea, the North Korean leadership scrapped plans to re-orient the economy toward the production of consumer goods and light industry and reinforced the pro-industry development strategy. Moreover, days after the coup, the leadership decided to simultaneously build up defense industries (a policy formally adopted in December 1962). These policies, by the end of the 1960s, resulted in a dramatic downturn in economic production in the DPRK; a downturn that was never reversed.

Jong-dae Shin is a professor at the University of North Korean Studies, Seoul, and a former Public Policy Scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center. Professor Shin’s current research focuses on North Korea’s foreign relations and inter-Korean relations during the 1970s. His numerous publications include Principal Issues of South Korean Society and State Control (co-author) (Yonsei University, 2005), Theory of Inter-Korean Relations (co-author) (Hanul, 2005), The Dynamics of Change in North Korea: An Institutionalist Perspective (co-author) (Kyungnam University Press, 2009), and U.S.-ROK Relations during the Park Jung Hee Administration (coauthor) (Academy of Korean Studies, 2009).

Christian F. Ostermann is director of the History and Public Policy Program (HAPP) as well as the director of European Studies (ES) at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Under his purview as director of HAPP and ES, Ostermann also oversees the Cold War International History Program (CWIHP), the European Energy Security Initiative (EESI), the North Korea International Documentation Project (NKIDP) and the Nuclear Proliferation International History Project (NPIHP). Additionally, Ostermann has chaired the Ion Ratiu Democracy Award since 2006, and currently serves as a co-editor of Cold War History as well as an editor of the CWIHP Bulletin.

James Person the Senior Program Associate for the History and Public Policy Program and coordinator of the North Korea International Documentation Project at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. He is a PhD candidate in modern Korean History at the George Washington University. His dissertation is titled “Solidarity and Self-Reliance: The Antinomies of North Korea’s Juche Thought, 1953-1967.”

***

DOCUMENT LIST

(click document title to be redirected to the Wilson Center Digital Archive)

DOCUMENT NO. 1

Journal of Soviet Ambassador in the DPRK A.M. Puzanov for 23 March 1960

DOCUMENT NO. 2

Journal of Soviet Ambassador in the DPRK A.M. Puzanov for 12 April 1960

DOCUMENT NO. 3

Journal of Soviet Ambassador in the DPRK A.M. Puzanov for 20 April 1960

DOCUMENT NO. 4

Journal of Soviet Ambassador in the DPRK A.M. Puzanov for 21 April 1960

DOCUMENT NO. 5

Journal of Soviet Ambassador in the DPRK A.M. Puzanov for 26 April 1960

DOCUMENT NO. 6

Journal of Soviet Ambassador in the DPRK A.M. Puzanov for 2 May 1960

DOCUMENT NO. 7

Journal of Soviet Ambassador in the DPRK A.M. Puzanov for 24 May 1960

DOCUMENT NO. 8

Journal of Soviet Ambassador in the DPRK A.M. Puzanov for 29 May 1960

DOCUMENT NO. 9

Journal of Soviet Ambassador in the DPRK A.M. Puzanov for 1 June 1960

DOCUMENT NO. 10

Journal of Soviet Ambassador in the DPRK A.M. Puzanov for 11 June 1960

DOCUMENT NO. 11

Journal of Soviet Ambassador in the DPRK A.M. Puzanov for 24 July 1960

DOCUMENT NO. 12

Journal of Soviet Ambassador in the DPRK A.M. Puzanov for 25 July 1960

DOCUMENT NO. 13

Journal of Soviet Ambassador in the DPRK A.M. Puzanov for 14 August 1960

DOCUMENT NO. 14

Journal of Soviet Ambassador in the DPRK A.M. Puzanov for 24 August 1960

DOCUMENT NO. 15

Journal of Soviet Ambassador in the DPRK A.M. Puzanov for 25 August 1960

DOCUMENT NO. 16

Journal of Soviet Ambassador in the DPRK A.M. Puzanov for 5 October 1960

DOCUMENT NO. 17

Note about a Conversation in the Soviet Embassy with Comrade Puzanov, 30 August 1960

DOCUMENT NO. 18

Journal of Soviet Ambassador in the DPRK A.M. Puzanov for 7 October 1960

DOCUMENT NO. 19

Journal of Soviet Ambassador in the DPRK A.M. Puzanov for 7 December 1960

DOCUMENT NO. 20

Journal of Soviet Ambassador in the DPRK A.M. Puzanov for 13 December 1960

About the Authors

Jong-Dae Shin

Assistant Professor, University of North Korean Studies; Director for Planning, Institute for Far Eastern Studies, Kyungnam University, Seoul, Korea

Christian F. Ostermann

Woodrow Wilson Center

James Person

Professor of Korean Studies and Asia Programs, JHU SAIS; Senior Fellow, Foreign Policy Institute, SAIS

North Korea International Documentation Project

The North Korea International Documentation Project serves as an informational clearinghouse on North Korea for the scholarly and policymaking communities, disseminating documents on the DPRK from its former communist allies that provide valuable insight into the actions and nature of the North Korean state. It is part of the Wilson Center's History and Public Policy Program. Read more

Cold War International History Project

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Through an award winning Digital Archive, the Project allows scholars, journalists, students, and the interested public to reassess the Cold War and its many contemporary legacies. It is part of the Wilson Center's History and Public Policy Program. Read more

History and Public Policy Program

The History and Public Policy Program makes public the primary source record of 20th and 21st century international history from repositories around the world, facilitates scholarship based on those records, and uses these materials to provide context for classroom, public, and policy debates on global affairs. Read more

Hyundai Motor-Korea Foundation Center for Korean History and Public Policy

The Center for Korean History and Public Policy was established in 2015 with the generous support of the Hyundai Motor Company and the Korea Foundation to provide a coherent, long-term platform for improving historical understanding of Korea and informing the public policy debate on the Korean peninsula in the United States and beyond. Read more