The Anna Chennault Affair: The South Vietnamese Side of the War's Greatest Conspiracy Theory

For the first time, Saigon’s point of view on the "Anna Chennault Affair."

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

For the first time, Saigon’s point of view on the "Anna Chennault Affair."

In October 1968, South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu refused to join the opening of the 1968 Paris Peace Talks that would end the war in Vietnam. Thieu’s refusal created a major crisis with his American ally.

President Lyndon Johnson speculated that Thieu’s decision was due to a backroom deal between Thieu and then-Republican presidential candidate Richard Nixon – a plot now branded as the “Anna Chennault affair,” one that has sparked numerous books and articles.

As part of the conspiracy, Nixon supposedly tapped Anna Chennault, the Chinese-born widow of wealthy businessman Claire Chennault, to serve as a backchannel to the South Vietnamese president via his ambassador to the United States, Bui Diem. Nixon, as the story goes, was trying to prevent a last-minute political bombshell by Johnson – the cessation of bombing North Vietnam – that would swing the election to Democratic Party candidate Hubert Humphrey. As president, Nixon would then support Thieu’s peace demands. Johnson’s theory was that Nixon had secretly convinced Thieu to not attend the opening of the Paris peace talks in order to torpedo Humphrey’s momentum heading into election day and hand Nixon the election.

Whether or not Nixon and his accomplices violated US law for political gain has been the subject of considerable speculation, but a critical aspect of the alleged Chennault plot – the South Vietnamese side of the story – has always been missing.

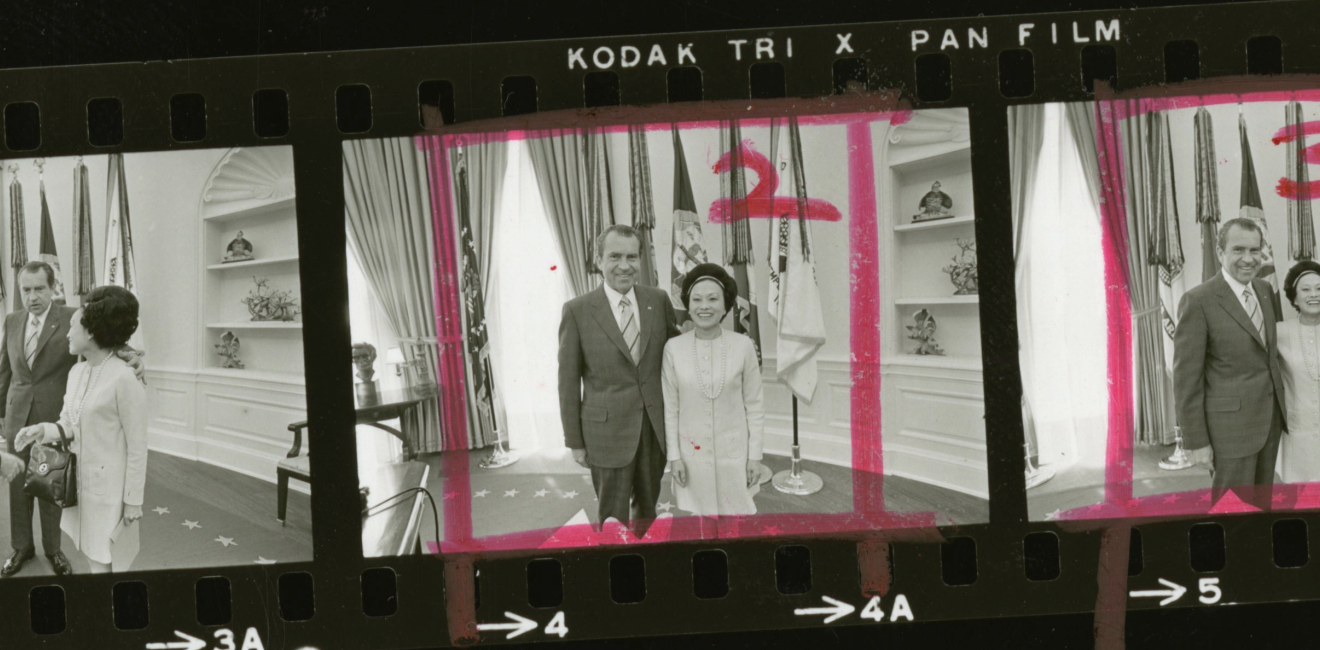

Anna Chennault was a wealthy socialite and renowned hostess to Washington’s elite. After her husband’s death in 1958, she retained control of his aviation company, which had substantial contracts to haul cargo from America to South Vietnam. Given her contacts with South Vietnam’s top leaders, she was an invaluable source of information about the country. In 1967, Nixon asked her to provide insights on the conflict and to act as a liaison between himself and the government there. Impressed by Nixon’s stated desire to win in South Vietnam, Chennault agreed.

The unmasking of the supposed plot occurred early on October 29, 1968.

A source in the Nixon campaign told economist Alexander Sachs that Nixon was trying to convince Saigon not to attend the Paris talks. Sachs passed the information to National Security Advisor Walt Rostow, who passed it to President Johnson. When Thieu suddenly refused that same day to participate in the Paris talks, Johnson ordered the FBI to wiretap Bui Diem and to follow Chennault to discover any plot with Nixon.

On the night of October 31, 1968, just after Johnson had announced a bombing halt of North Vietnam in exchange for the opening of talks in Paris with the North Vietnamese, Chennault says she received a phone call from Nixon advisor John Mitchell. He called to express his concern about the impact of the announced bombing halt on the election. Mitchell said that he was speaking on behalf of Nixon, and that he wanted her to communicate the “Republican position” to the South Vietnamese. She claims she was upset by Mitchell’s demand, as it would have changed her role from a Nixon advisor to someone advocating a policy change.

Two days later, in probably the only damning piece of evidence collected, the FBI recorded a call from Chennault to Bui Diem. She “advised him that her boss…wanted her to give personally to the ambassador” a message to “hold on, we are gonna win.”

By “boss” she claimed she had meant Mitchell, but Johnson thought she meant Nixon. The fact that Thieu had suddenly refused to send representatives to attend the talks, followed by Johnson’s actions to wiretap Bui Diem and have FBI agents follow Chennault, alongside the recording of the conversation, created the enduring legend.

There are several flaws in this version of the “Chennault affair” theory. First, Chennault did not pass Mitchell’s message to Bui Diem for two days. If she were using Bui Diem as a courier for the Nixon camp, one would assume a communication of this importance would have been delivered immediately.

Equally important, the transcript of the call does not indicate any response by Bui Diem. He did not attempt to discuss or clarify her message, nor did he mention her call in any subsequent cable to Saigon. If he were passing messages, such an urgent contact would have been quickly transmitted back to Thieu. The NSA, which was monitoring South Vietnamese diplomatic traffic, would have then intercepted it and provided it to Rostow. Such a cable would have provided concrete evidence of the plot, but no such document exists. For his part, Ambassador Bui Diem repeatedly denied making any deals with the Nixon campaign to sabotage the peace talks. Bui Diem told me in an interview that he did not report her message because “it did not mean anything or change the situation.” Chennault herself also rejected the allegations.

In interviews with South Vietnamese who were involved in the peace negotiations, they insist they did not attend the Paris talks because of the political issues, not because of a Nixon request.

However, they relate a stunning reality: the writers who describe a Nixon plot have the conspiracy backwards. According to my interviews with former South Vietnamese officials, and focused solely on US evidence and Nixon’s later Watergate crimes, believers of the Chennault conspiracy missed the possibility that Thieu and his Asian allies may have tried to manipulate the US election for their own advantage.

The truth is that Chennault did attempt to convince Thieu not to attend the Paris talks, but she did so at the behest of Chinese nationalist leader Chiang Kai-Shek, not Nixon. Moreover, Chennault did not use Bui Diem as a conduit. Instead, she relied on Thieu’s brother, Nguyen Van Kieu, the South Vietnamese Charge d’Affaires in Taipei, as her main conduit.

Chiang Kai-shek speculated that Lyndon Johnson might abandon not only South Vietnam but also Taiwan. Out of his own self-interest, Chiang wished to see a South Vietnamese military victory, and tapped Chennault to relay his views and advice to the leadership in Saigon. Kieu had long acted as Thieu’s go-between with various constituencies in South Vietnam, and he reportedly helped to arrange one highly secret meeting in Vung Tau between Chennault and Thieu. A faithful intermediary, Chennault is said to have shared Chiang’s advice to President Thieu that Saigon not cave to US demands and Chiang’s hope that Nixon would emerge victorious in the presidential election.

Aside from the advice from Chiang, Thieu had his own reasons to undermine American eagerness for talks with Hanoi. In a rare post-war interview, Thieu denied he was directly influenced by a Nixon scheme. He repeated that his refusal to attend the Paris talks was due to the twin failures to arrange negotiations between Hanoi and Saigon and to prevent the presence of the National Liberation Front at the talks.

In an interview with journalist Neil Sheehan in June 1975, Bui Diem laid out his conjecture about what transpired, one likely closer to the truth. He told Sheehan there was no reason to “weave a complicated plot” because the “dynamics of the situation were so obvious” based upon “Saigon’s assessment of the positions of the candidates on Vietnam… The basic reason Saigon favored Nixon” was due to Thieu’s belief that “Nixon was ‘firm against the Communists’ while ‘Humphrey was wavering.’”

Ultimately, the “Anna Chennault Affair,” is an example of how partisanship and political intrigue, combined with conjecture, result in broad acceptance of wrongful narratives. Anna Chennault was the go-between for Chiang and Thieu, but evidence suggests that she was only a messenger. Political historians would do well to embrace the facts as they stand and do away with one of the Vietnam War's great conspiracy theories.

This is an excerpt from George J. Veith's book Drawn Swords in a Distant Land: South Vietnam’s Shattered Dreams (Encounter Books, 2021).

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more