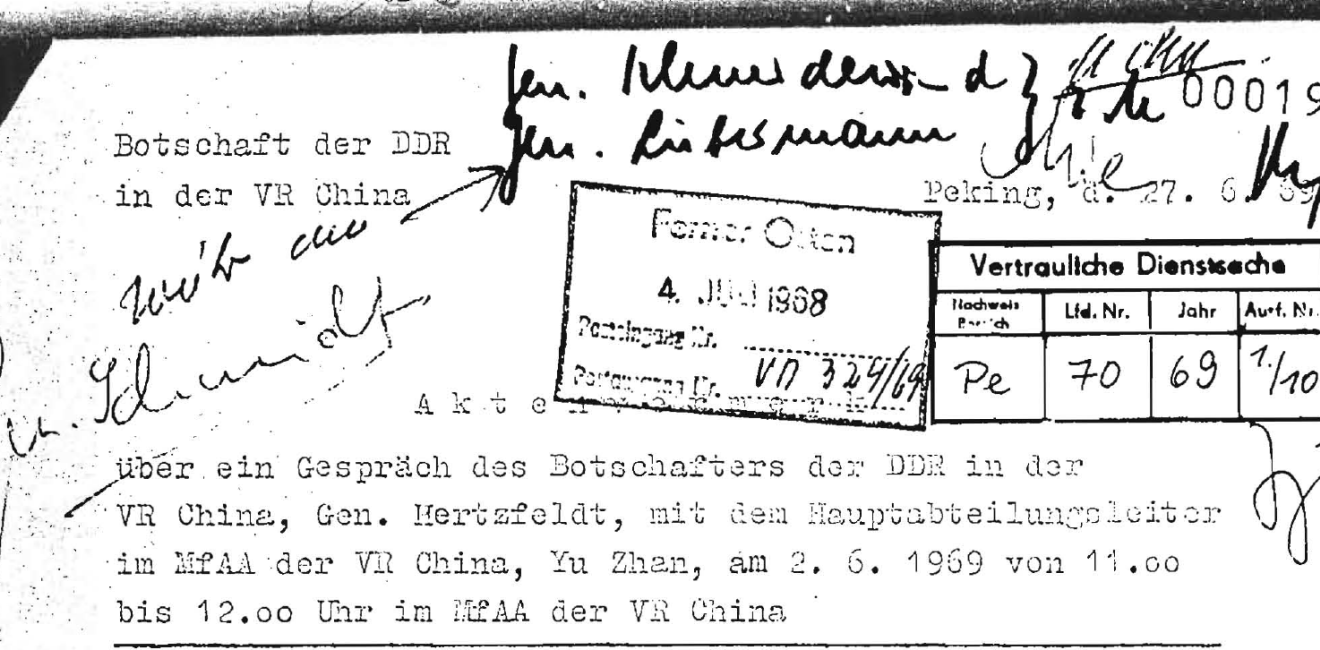

On 2 June 1969, the East German ambassador to Beijing, Gustav Hertzfeld, met with the head of the Main Department in the Chinese Foreign Ministry, Yu Zhan. The meeting took place at the apogee of the Sino-Soviet split, and the record of the encounter clearly illustrates the tense atmosphere inside the communist world. Both Hertzfeld and Yu Zhan took turns to accuse each other’s country of failing to offer fraternal assistance.

What is perhaps most striking throughout the conversation is the unequivocal refusal of both officials to compromise on their respective country’s policies and to try and resolve what Yu Zhan described as the “basic, irresolvable differences of opinion.” This comes through loud and clear in the inability of the two statesmen to agree on even one single political topic.

Furthermore, rather than debate these issues, the tone of the two men was accusatory and critical. Already at the start of the conversation, Hertzfeld harangued the Chinese government for its lack of propaganda in support of East Germany’s endeavour to nullify the Hallstein Doctrine and achieve legitimacy on the international stage. To be sure, in 1969, the Ulbricht government achieved several diplomatic breakthroughs, notably, state recognition from non-communist nations, such as the Kingdom of Cambodia, the Sudan, Egypt and Iraq. Despite this “severe blow against imperialism, especially that of West Germany,” Hertzfeld complained that not even the “basic facts” had been reported in the Chinese press.

Nevertheless, throughout the conversation, it becomes ever more evident that neither Ambassador Hertzfeld nor the GDR were considered a priority by Beijing. For instance, the Chinese ambassador in East Berlin had been withdrawn and there was no sign that a replacement would be sent anytime soon. Yu Zhan likewise did not respond to Hertzfeld’s open request for future meetings with leading Chinese decision-makers and insisted that diplomats were being received “according to concrete needs.” At the same time, rather than justify the dearth of news about the GDR, Yu Zhan’s response comes across as rather nonchalant and dismissive, claiming that the press would not express the Chinese position “at every occasion” and that the press “has its own rules.”

Not only did Yu Zhan rebuff Hertzfeld’s complaints, he also explicitly criticised East Germany’s “certain vacillations” on the Berlin question and insisted that “really decisive measures” would precipitate more Chinese patronage. This was an implicit reference to the split between the two sides on strategy. Whereas the Soviet bloc preached “peaceful coexistence” with the imperialist countries, Maoist China conversely advocated a more dynamic policy, believing that the communist countries should not fail to utilize revolutionary conditions or exploit advantageous situations just because it risked nuclear war. Clearly, Yu Zhan judged the Ulbricht government’s stance on Berlin both inadequate and ineffective.

In turn, the archival document underlines East German concern about the specter of Beijing establishing diplomatic relations with its estern nemesis. As early as 1955, the West German Chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, had entertained the idea of exploiting the Sino-Soviet disagreement to gain leverage on Berlin and German reunification. It is telling that Hertzfeld mentioned the former West German Foreign Minister, Franz Josef Strauss, who, akin to Adenauer, had been one of the most outspoken advocates of rapprochement.

And yet, irrespective of Hertzfeld’s repeated request that the Chinese government publicly refute the possibility of a “Bonn-Beijing axis” and shatter West German eagerness of acquiring Chinese support for its national objectives, Yu Zhan refrained, again, from offering any indication that the PRC would quash these rumors. No doubt this was due to Mao Zedong’s theory of the “intermediate zone,” which stated that the secondary powers on both sides of the Iron Curtain wanted to unfetter themselves from the two superpower’s hegemony and pursue independent policies. As a result, the Chinese government was unwilling to close the doors on better relations with Bonn.

It was not only Hertzfeld, however, who believed that the other side was failing to satisfy the demands of communist unity. Yu Zhan pointed out that fraternal support needed to be “reciprocal” and, just like Hertzfeld, lamented the opposite side’s lack of assistance and cooperation. This is particularly noticeable when discussing the border clashes on the Sino-Soviet border. It is striking that, when talking about the Soviet Union, Yu Zhan’s tone became severely bitter and explicit. In his eyes, the USSR was both an “imperialist country” as well as a “friend” of the United States, which was endeavoring to wage war against Beijing.

Yu Zhan also made it plain that the GDR was not taking a disinterested stance on the crisis. He pointed out to the ambassador that East Berlin had published the Soviet’s report on the border clashes and simply returned the Chinese statement.

Finally, the language used by both officials is pertinent. Although Hertzfeld noted that the meeting proceeded in a “calm manner,” there is a striking despondency about the whole affair. At the end, Yu Zhan claimed that the problems would become “only bigger with the progress of this conversation” and that the PRC was “talking in the language of facts and, therefore, is correct,” suggesting that there was nothing that Hertzfeld could say which might change his mind. In a similar vein, Ambassador Hertzfeld acknowledged that “no agreement” would be “reached during this meeting.”

The “principled differences in opinion” were, in short, too deeply entrenched and paralyzed any prospect of either rapprochement or cooperation between the two sides.