A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

What official Chinese sources say—and don’t say—about the country’s recent history

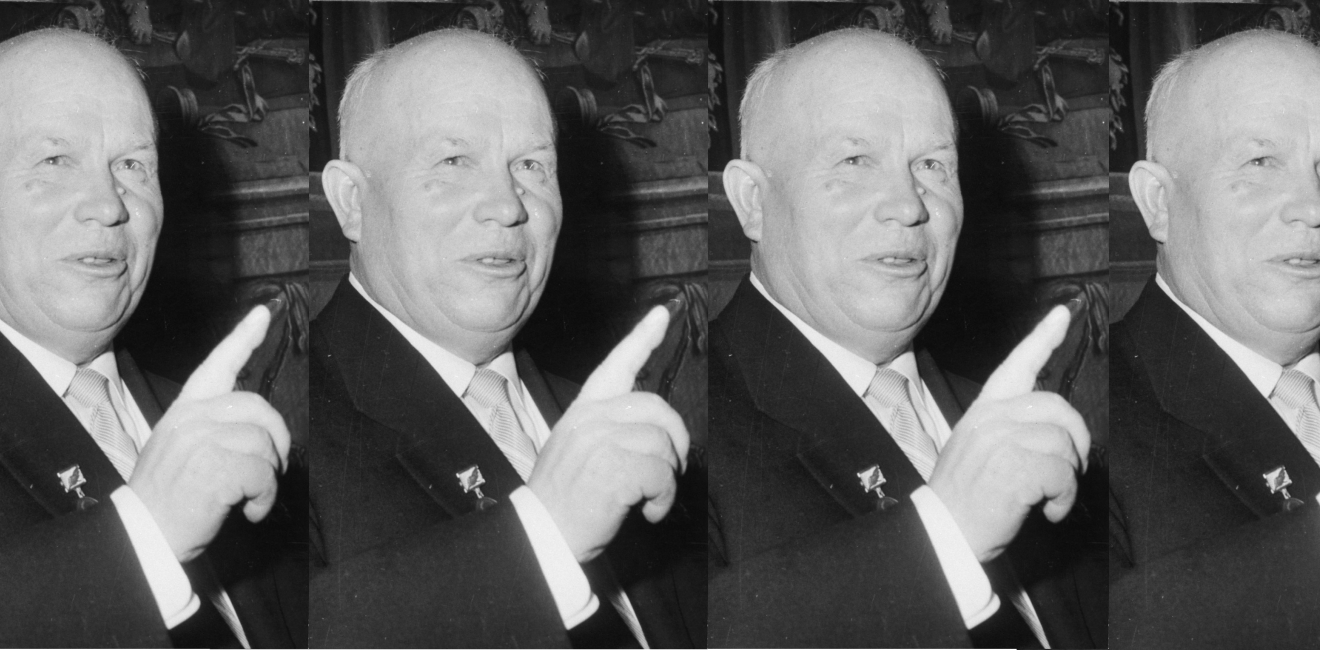

Of course this has something to do with anti-revisionism. There are big Khrushchevs and there are little Khrushchevs. Even a village has Khrushchevs. Schools? Factories? Neighborhoods? They all have Khrushchevs. Don’t think we’re so pure. – Deng Xiaoping, May 19, 1964

Official histories of the Chinese Communist Party are more available than ever before, but are they reliable enough to be used as trusted historical sources?

In recent years, China’s Party Literature Research Center, a research arm of the CCP’s Central Committee, has released a glut of new publications: from dense day-by-day accounts of an individual leader’s life (nianpu) to extensive multi-volume collections of documents (wenjian). In the 1990s and early 2000s, these sources were a boon to the China historian’s craft.

The digitization and online publication of many of the official texts has made them even more useful. Now full-text searchable, you can find out exactly when Mao met Ho Chih Minh and what they talked about at a moment’s notice.

Historians have long had their suspicions about whether these sources are reliable, but usually couldn’t offer a firm “yes” or “no” answer.

One of the most important developments following the partial opening of China’s archives is the ability to answer this question. For many important internal and diplomatic meetings that Chinese officials held after 1949, we can now crosscheck published information with contemporary internal records.

Take for instance, Deng Xiaoping’s meeting with Lê Bình, the Secretary of North Vietnam’s Labor Youth Union, on May 19, 1964.

In the official chronology of Deng Xiaoping’s life compiled by the Party Literature Research Center, the meeting is summarized in one short paragraph, about 270 Chinese characters. By contrast, the verbatim transcript of the conversation transcribed by China’s State Council and later stashed away in the Foreign Ministry Archive in Beijing is a whopping 18 pages—amounting to 9,000 or so Chinese characters.

We can see that the nianpu provides only a slither of a long-winded and extensive conversation between a Chinese leader and a foreign official. That’s probably to be expected: no book could reprint every word of every meeting that Deng ever held. So the issue is not necessarily how much the chronology leaves out, but what it leaves out. In this case, it is Deng’s critical and candid views on the situation in China.

At the time of the meeting with Lê Bình, Deng was a 60-year old Vice Premier still in Mao’s good graces. He had visited Moscow in July 1963 in an effort to mend fences with Nikita Khrushchev, but no agreement was reached and the relationship between the two major communist states only worsened thereafter.

As one might expect, Deng used the talk with the Vietnamese partially to reflect on the problems of Soviet “revisionism” and the ideological polemics between China and the USSR. The published chronology plays up this aspect of the conversation, summarizing Deng’s reflections on the patchy history of socialist construction in the Soviet Union. He criticized Stalin’s claim, for instance, that the Soviet Union had successfully completed socialist construction.

But there is a lot more going on in the original archival record, including some extensive commentary from Deng on China’s own bumpy road to socialism. After all, this is exactly what the Vietnamese wanted to hear about. At the opening of the conversation, Lê Bình remarked that:

During our trip in China, the Chinese comrades have introduced some successful experiences [in China’s socialist construction]. For us, this is very valuable. It would also be good if you were to introduce some failed experiences.

Deng indulged Bình’s request, depicting China as a country still in the midst of transitioning from socialism to communism. He even discussed the so-called “Three Years of Natural Disaster,” or the famine which followed Mao’s Great Leap Forward campaign. He blamed draught, Nikita Khrushchev’s revisionism, and “shortcomings and mistakes” (quedian cuowu) in the work of the Chinese Communist Party for inflicting so much pain on the Chinese people in the early 1960s. Deng’s Chronology makes no mention of these remarks.

Similarly, the nianpu masks the internal fissures within China during this period. According to Deng, the economic disaster wrought by the three forces mentioned above nurtured “revisionism” within China, both at the highest-levels of leadership and at the lowest rungs of society. He vehemently criticized the foreign policy of Wang Jiaxiang, by then a disgraced official. Wang had proposed “three reconciliations and one reduction”—that is, reconciling with India, the Soviet Union, and the US, and reducing support for Third World revolutionaries. “Is [this] not the same as Khrushchev?” Deng asked. “It becomes revisionism!”

Deng’s full commentary shows that China was locked in an ideological war with the Soviet Union, but that it was also effectively at war with itself. As he said to Lê Bình, in China, “there are big Khrushchevs and there are little Khrushchevs. Even a village has Khrushchevs. Schools? Factories? Neighborhoods? They all have Khrushchevs. Don’t think we’re so pure.”

The actual transcript of the conversation also reveals Deng’s suggestions for overcoming these “revisionist” influences and establishing the foundations for China’s eventual transition to communism. Deng wanted to train faithful red technocrats, and called for the ideological and physical transformation of intellectuals and students. A pragmatist, Deng also sought to boost incomes and reduce disparities across political and social classes, something he thought the Soviet Union had failed to do.

This example confirms historian's well-founded suspicions about China’s officially complied sources and should serve as a cautionary tale for accepting these records at face value. The chronologies, or nianpu, are curations, subject to space limitations and the editorial biases of the committee’s behind them.

Authors

History and Public Policy Program

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

Cold War International History Project

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more

Explore More in Sources and Methods

Browse Sources and Methods

Energy and the Fall of Détente

Kissinger, Dobrynin, and the End of the Vietnam War